When you hear the word Design Sprint, what comes to mind?

If you’ve just started your career, you might think, “Oh no! It must have something to do with designing quickly.”

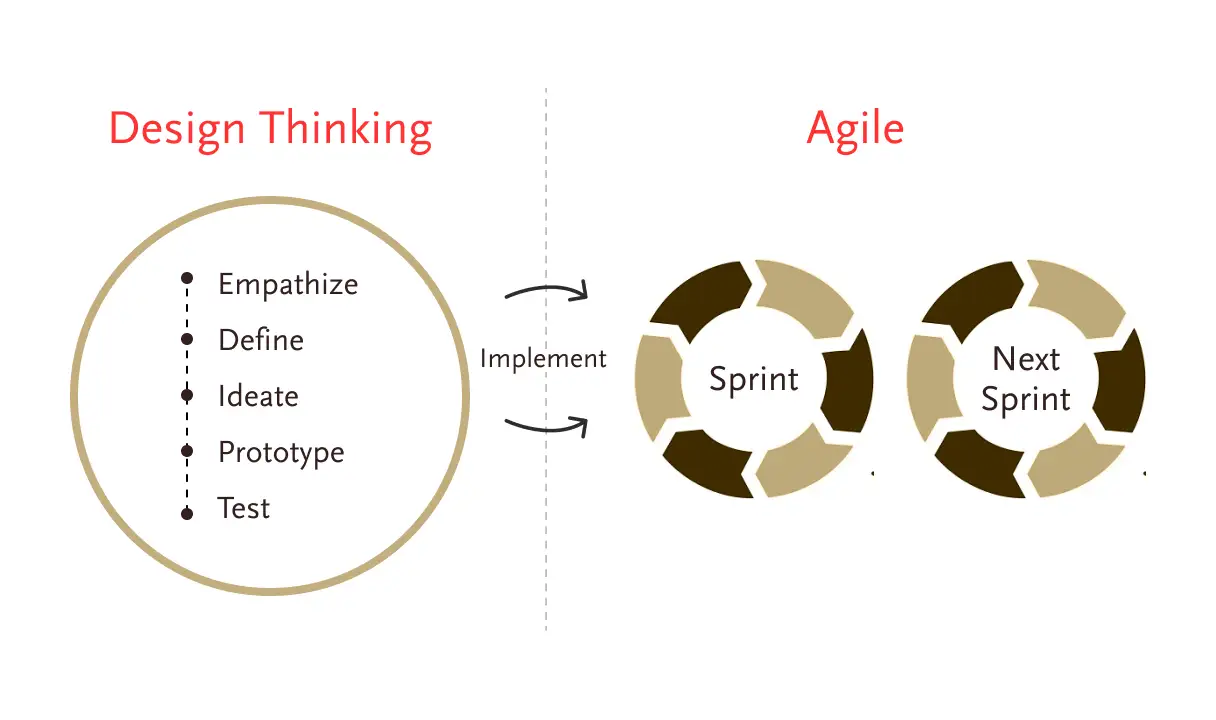

But if you’re more seasoned, you know it’s really an amalgam of Design Thinking and Agile Sprint.

If you don’t know what Design Thinking is, read about it here and then come back. A Sprint is a one‑to-four-week cycle in Scrum (an Agile framework) to complete a product feature.

Design Sprint = Design Thinking Lite

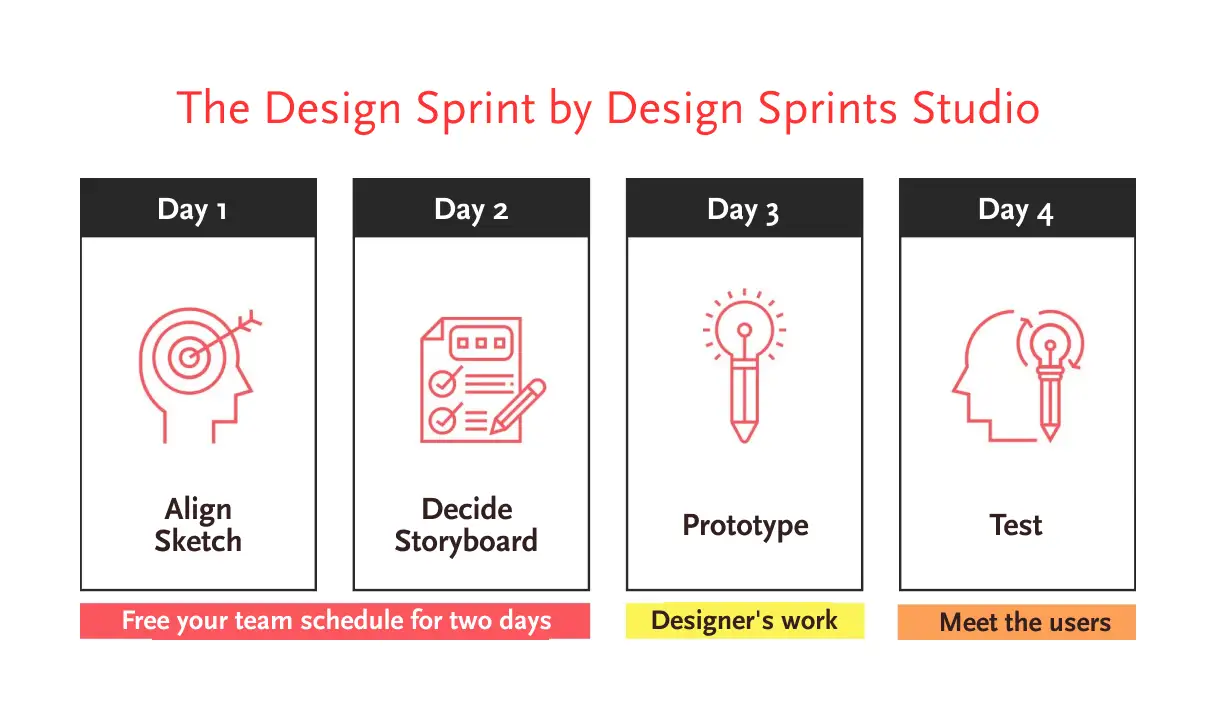

A Design Sprint is a lighter, faster version of Design Thinking. It (used to) follows the same steps, preaches the same philosophy, and uses the same tools and techniques to solve problems. However, it differs in two ways:

- It’s time-bound, and

- It’s linear

If Design Thinking is a marathon, Design Sprint is, well, a sprint 😉. And you have to finish it within a week without straying from the path. From Monday to Saturday, you get 6 days—one for each step of the framework.

But if you don’t work long hours, avoid weekends, or don’t buy Mr. Narayana Murthy’s “70-hour work week,” you can carry the Sprint over into Monday. Either way, the rule is clear: work hard, move fast.

Difference Between Design (Thinking and Sprint)

First, Design Thinking is an overarching framework that considers every aspect of a product. That is why executing it often takes months, demands huge resources, and requires constant collaboration. Even then, success isn’t guaranteed. You still have to wait and watch to see how the product performs in the market. For this reason, Design Thinking is limited to large enterprises, corporations, and academics.

On the other hand, a Design Sprint can be completed in a week, requires fewer resources, and allows for greater flexibility. While Design Thinking is a robust and comprehensive framework, Design Sprint often proves a more practical option in the fast-moving environment.

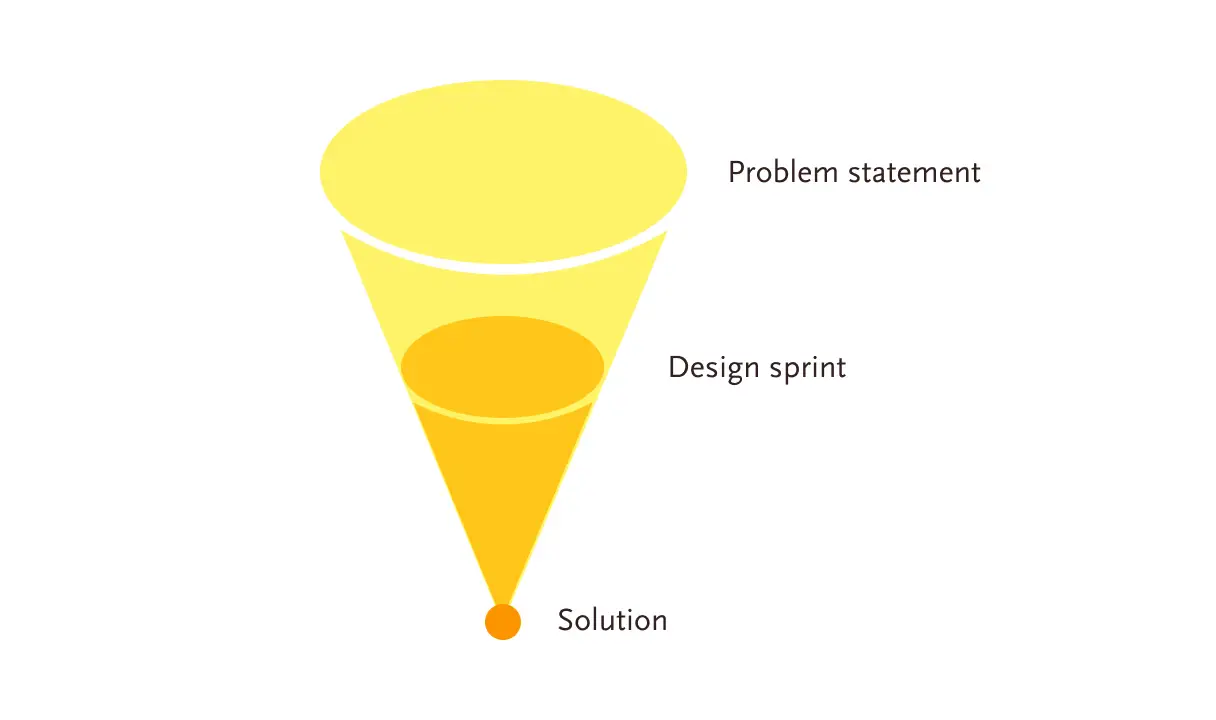

Second, one of the primary goals of Design Thinking is to nail the problem statement. Since a product’s success hinges on framing the right problem, teams invest a lot of time exploring all possibilities, validating assumptions, and leaving no stone unturned before committing to one.

In a Design Sprint, however, you don’t have the luxury of discovering insights. There isn’t time to go into the field and conduct research. That’s why you must begin a Sprint with a problem statement already in hand.

Let’s take a closer look at what a Design Sprint is and how it works.

Google Design Sprint

The name itself clearly indicates someone at Google proposed the idea. In the beginning, Jake Knapp and his team at Google Ventures used this method on a lot of new ventures they had easy access to. Later, other Google folks refined it over the years and made it what it is today.

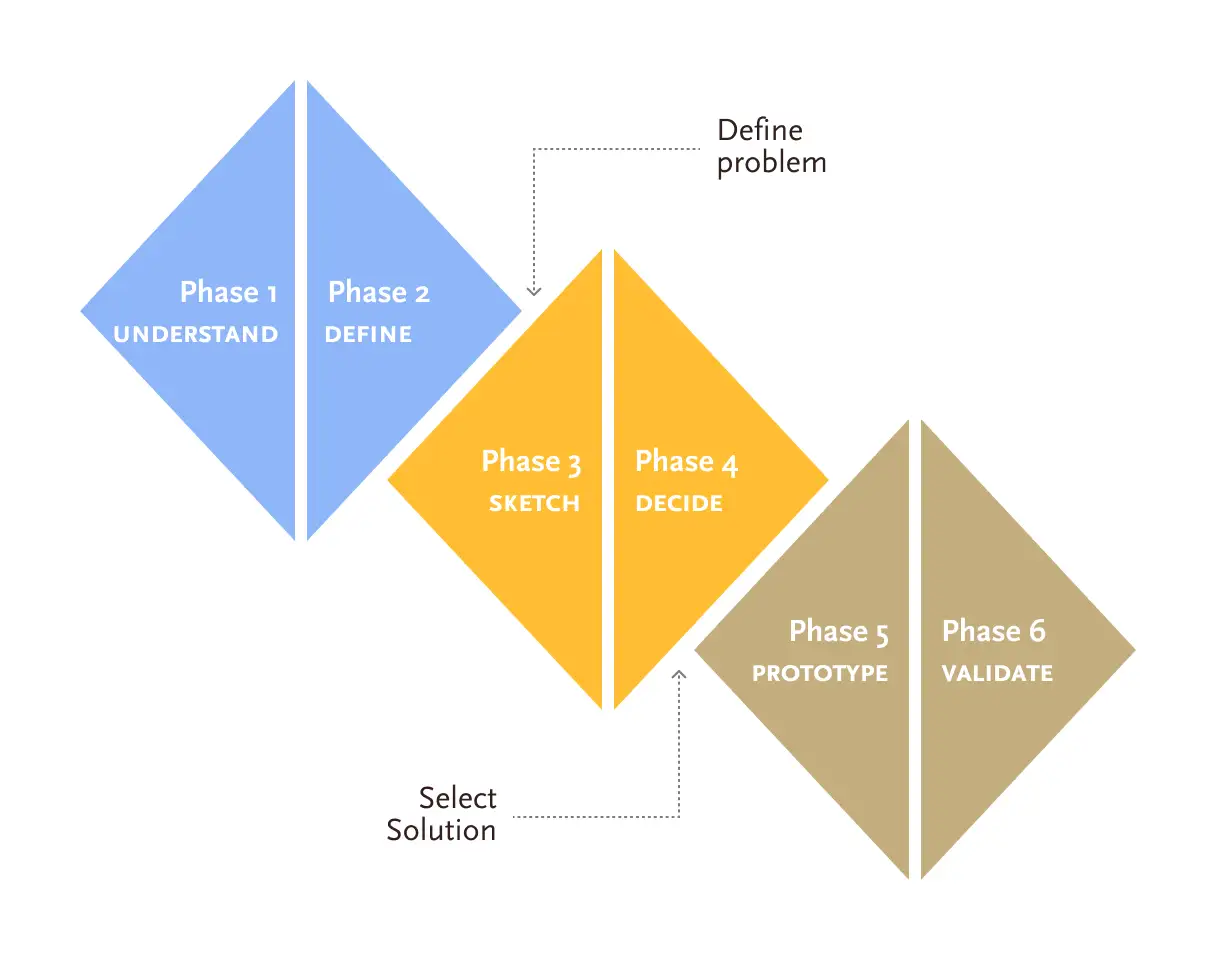

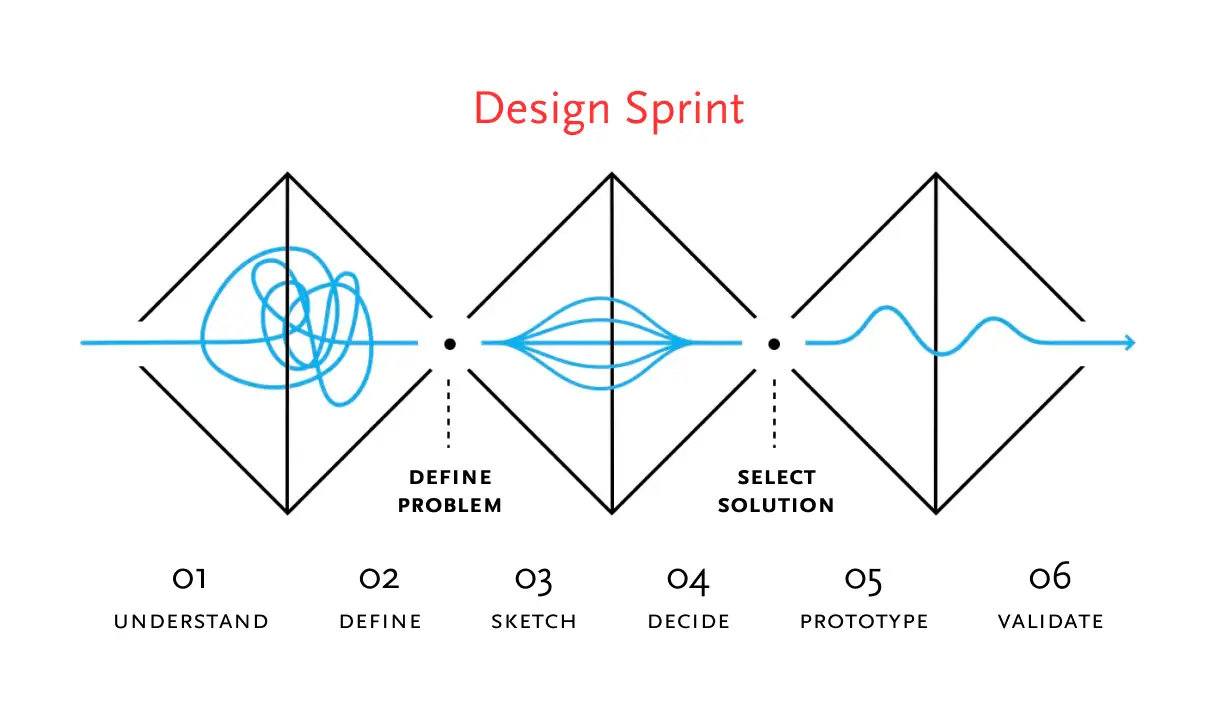

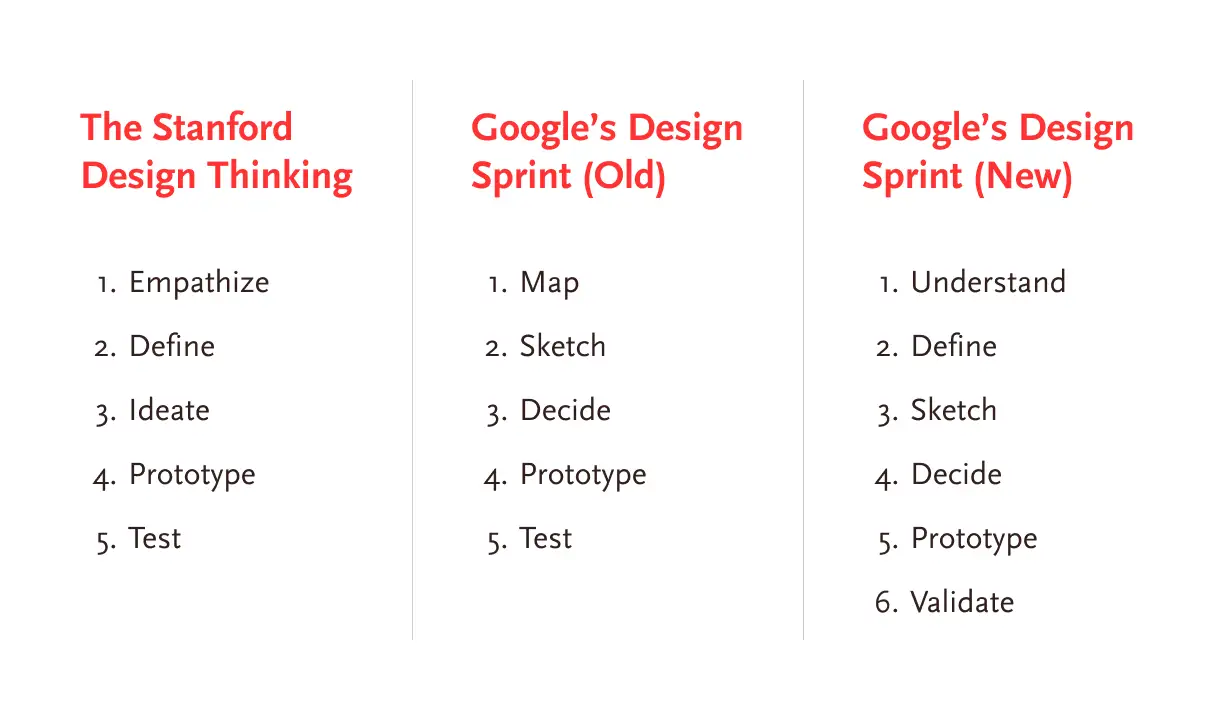

Much like the Stanford d.school’s five-phase Design Thinking framework, the classic Design Sprint also had five phases fitting nicely into five weekdays. Teams just had to block their calendars for a week and be done with it. Now, with its six phases, it spills into the next week, breaks the flow, and basically becomes problematic overall.

But you’re not forced to follow the exact methodology. You can use the classic Design Sprint, the new version, or create your own flavor. For now, let’s set that aside and see what they actually offer.

Let’s start with the Understand phase of the latest Google’s Design Sprint, compare it with other processes, and do this activity for all the phases to better understand them.

1. Understand

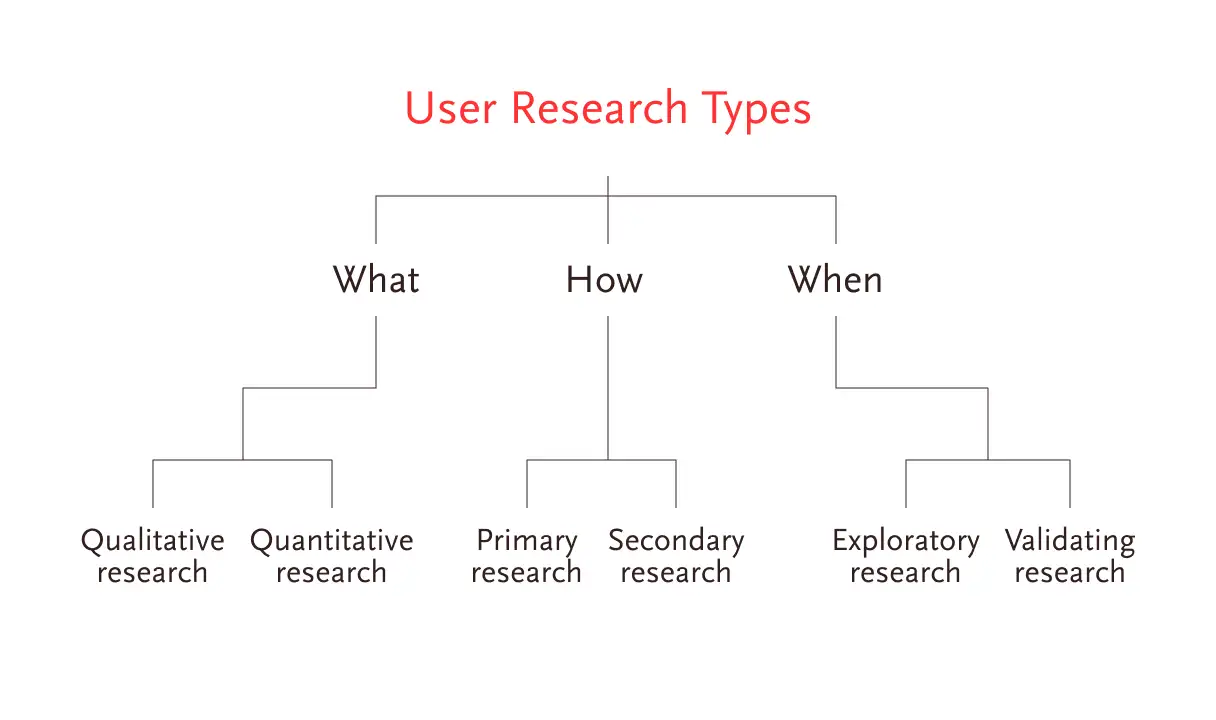

In Google’s Design Sprint, the “Understand” phase aligns with “Empathize” in Design Thinking and the “Map” in its earlier version. But no matter what you call them, they all point to the same thing: user research.

The key difference lies in the scope of user research. In a Design Sprint, you can’t conduct full-fledged research. You simply don’t have the time. You get just a day, or more precisely about eight hours, to understand the problem.

In that time, you can bring together knowledge experts—designers, developers, managers, marketers, etc.—and work to understand the problem or opportunity. This could be an issue customers are facing, a new feature users have requested, or a design you want to innovate. Whatever it is, the goal is to create a shared understanding within your team.

In simple terms, you already have a problem statement, you’re just not sure how good it is. And you don’t want to commit resources without validation. The aim is to create a single source of truth where everybody knows: what the problem is, who the users and competition are, what deliverables are expected, which metrics are crucial, and what success looks like.

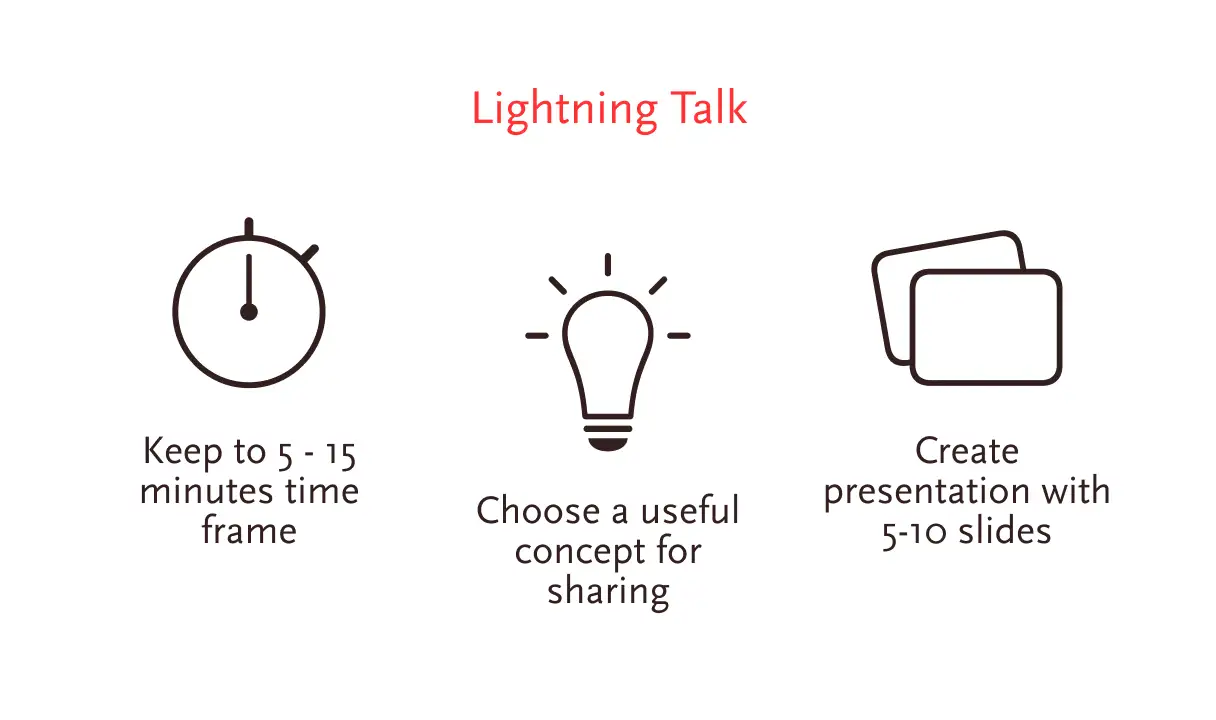

To figure out all those things, Lightning Talks are your best bet. In these sessions, people with relevant knowledge share their insights in 10–15 minutes. Even better if you prepare a presentation that covers:

- Business goal

- User insights

- Competitive products

- Technical opportunities

Once everyone fully understands the problem or opportunity, you move forward to the next phase.

2. Define

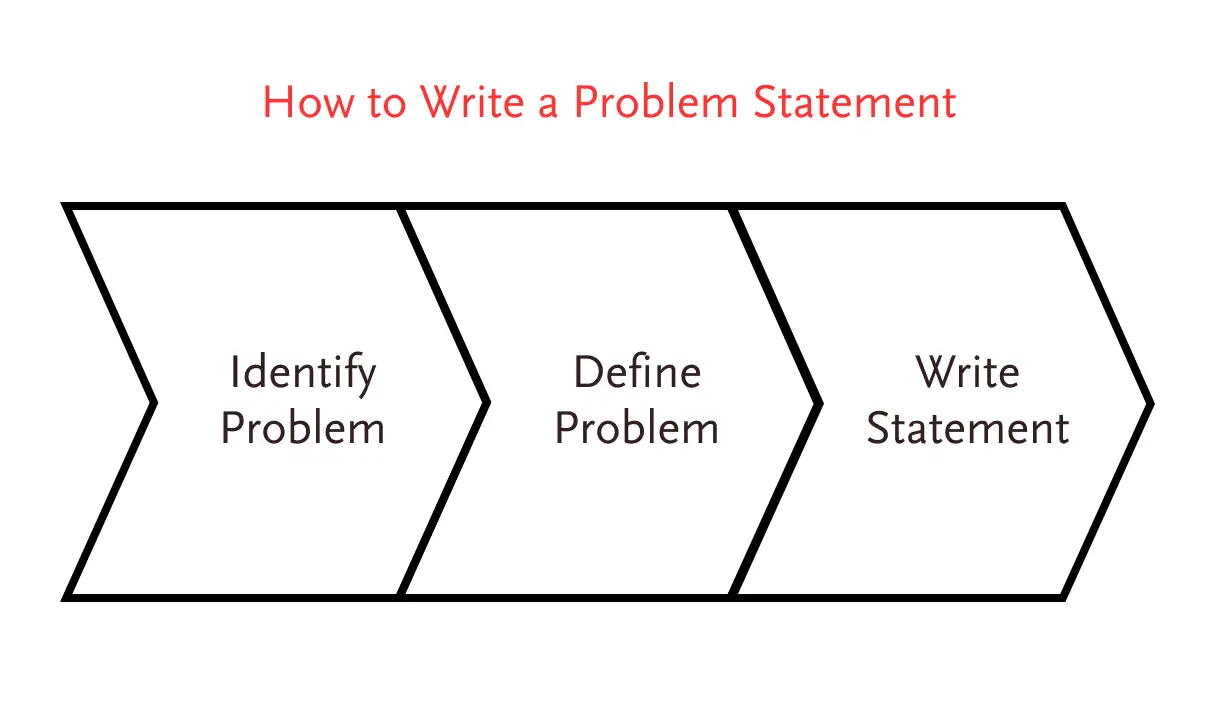

Although “Define” is the second step in Design Thinking, it was missing in the first version of the Sprint when Google introduced it. At first, they combined both understanding and defining the problem in a single phase. Now, there is an entire day dedicated just to defining the problem.

In the previous phase, you understood what the problem was. But unless you clearly write it down, your team may get confused about what is expected from them. So before encouraging your team to find solutions, first define the problem in concrete terms. For example:

- Who are the users, and what are their characteristics?

- What are their needs and desires?

- Why do you want to fulfill these needs and desires?

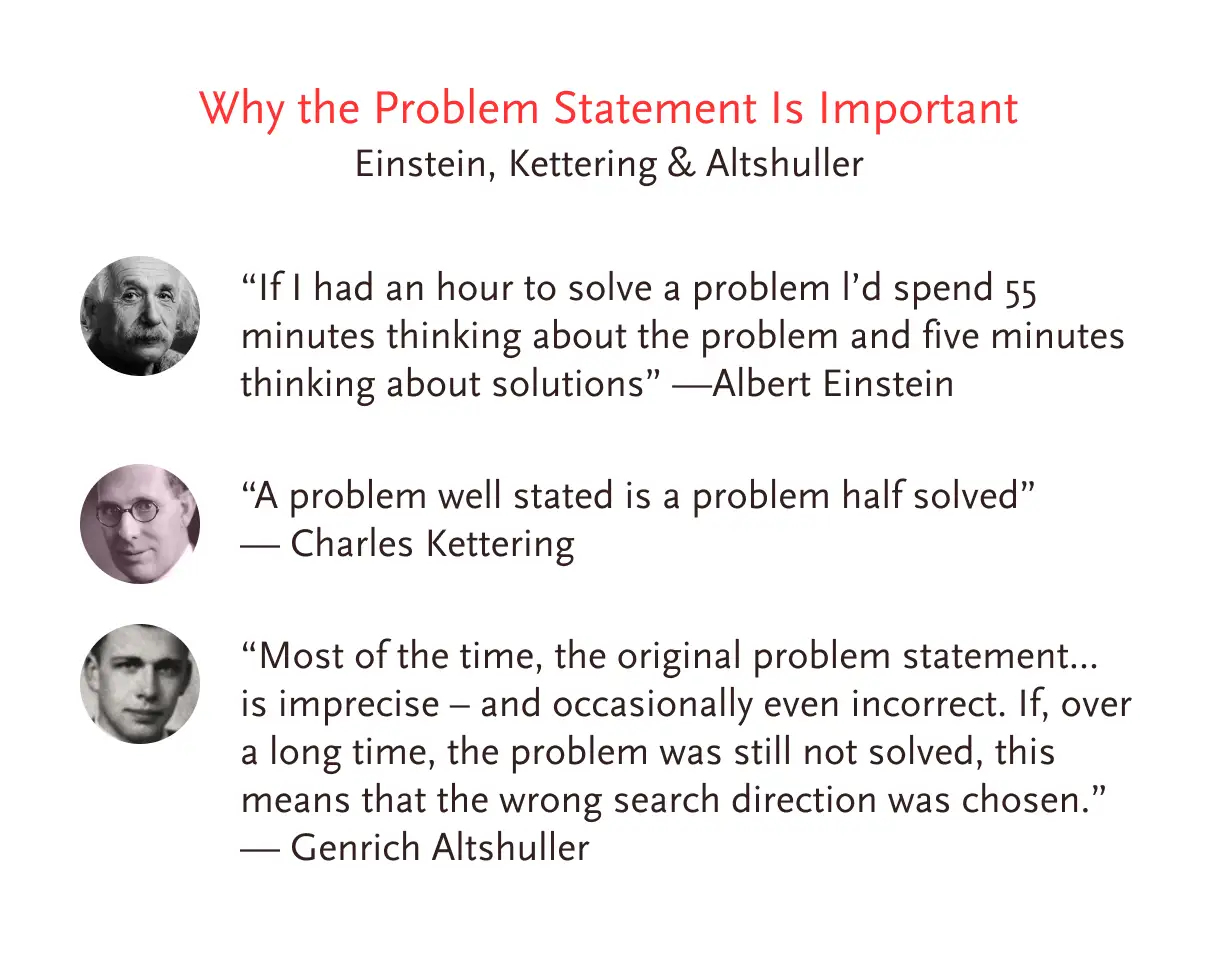

And of course, you’ll need metrics to determine whether you succeed or not — a yardstick against which to measure progress. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets improved.

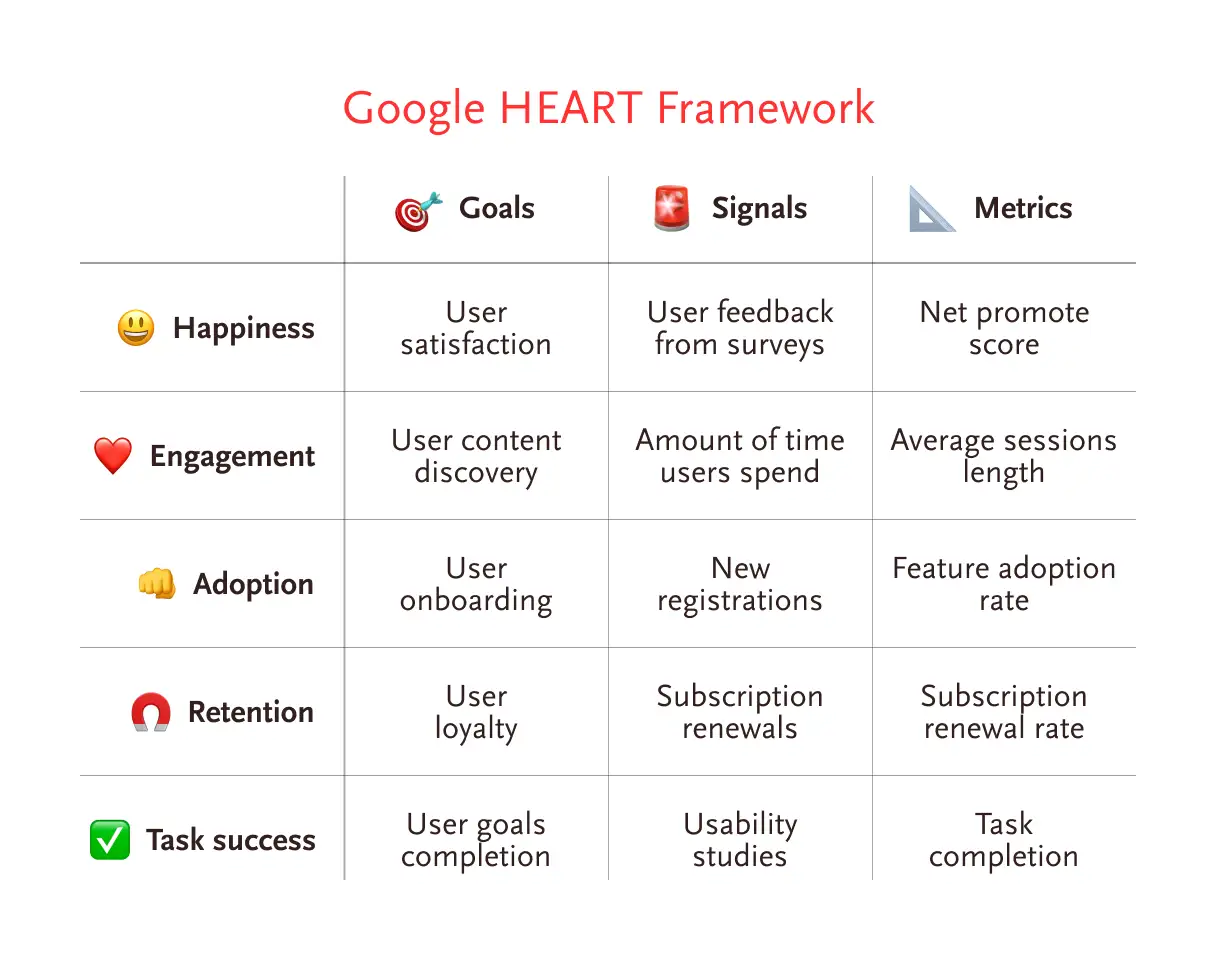

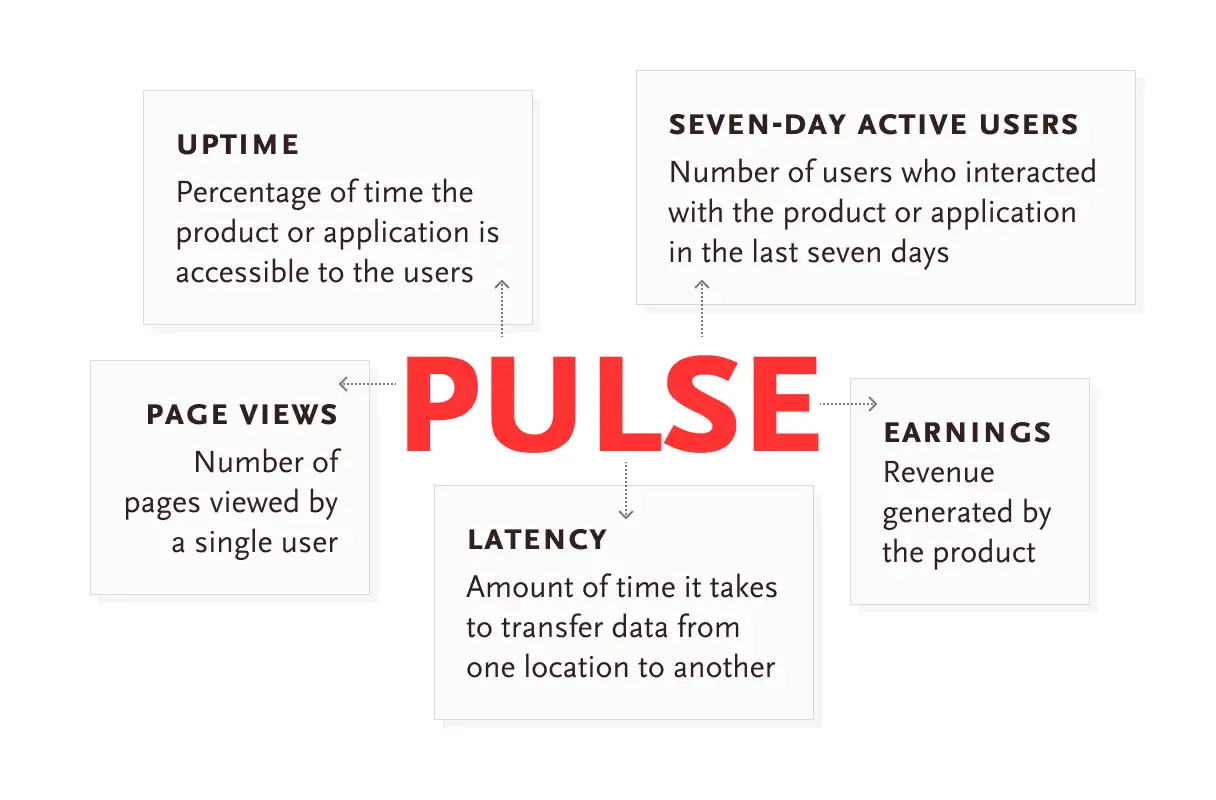

Here, you can use Google’s HEART framework along with PULSE metrics to define how you’ll measure your goal:

- Happiness — Metrics that capture user attitudes. Example: satisfaction, visual appeal, perceived ease of use

- Engagement — The user’s level of involvement with the product. Example: number of visits per user per week

- Adoption — The number of new users gained within a time period. Example: accounts created in the last 7 days

- Retention — The number of users who continue using the product over time. Example: subscription renewal rate, churn rate Task

- Success — Metrics that measure efficiency, effectiveness, and error rate. Example: time to complete a task

Once you’ve defined the problem and established your success metrics, you can move to the next phase: Sketch.

3. Sketch

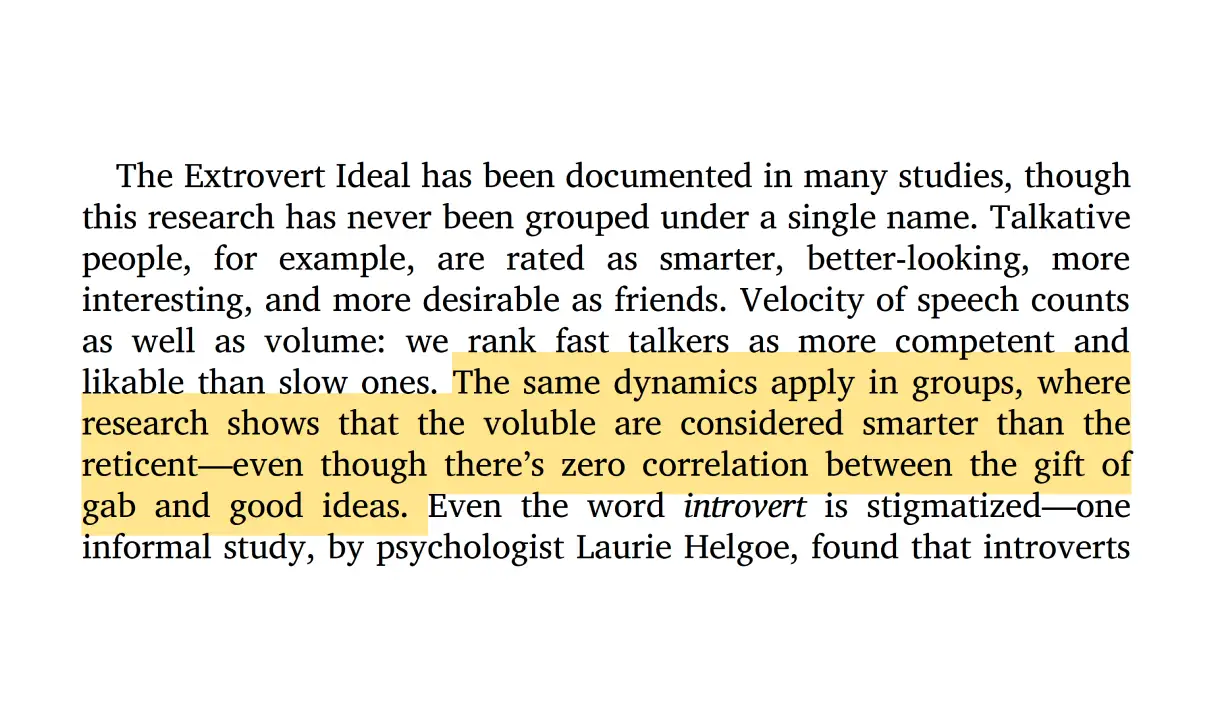

In the Sketch phase, each individual works alone to generate solutions. While brainstorming is a great method to generate ideas, introverts don’t get as much exposure or opportunity as they should. Even if they get equal chances to speak up, they don’t feel comfortable sharing their thoughts.

That’s why sketching offers many benefits:

- Sketching is quick & easy. You can create and discard ideas freely. Since you spend a little time drawing them, you don’t feel attached to them.

- You also don’t need to know any wireframing tools. Even people who are not tech-savvy can participate.

It is easy to speak your mind, but when you draw/write, you are forced to think more deeply and examine the problem from multiple angles. So rather than speaking and letting others find holes in your ideas, sketching helps you spot them yourself.

The best way to find a great idea is to have a lot of ideas. So the goal in this phase is to create as many ideas as possible. And don’t limit your imagination—explore ideas that may not even make sense. Don’t judge them too early, evaluation will come later. This phase is all about generation.

One of the exercises that Google recommends is Crazy 8, where you fold an A4 sheet several times to create 8 sections. And then you draw one idea per section. But other than that you can use whatever method you find effective. Once you have gathered enough ideas, move on to the next stage: Decide.

4. Decide

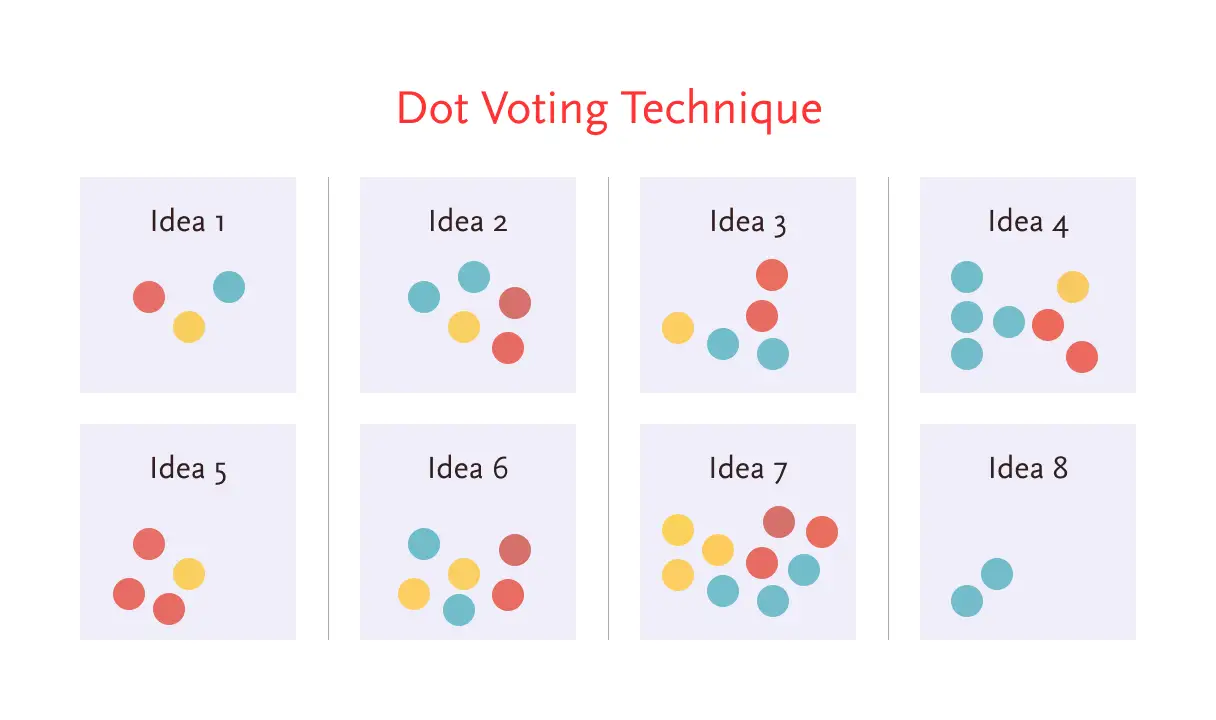

In this phase, each participant gets a chance to present their ideas and briefly talk about them. After reviewing all the ideas, the team selects a few promising ones and displays them on a wall.

Then, everyone is invited to cast their vote. They can either use dot voting or they can simply mark a dot with a pen on the ideas they prefer. And based on the number of votes each idea receives, the team decides which ones to move forward with.

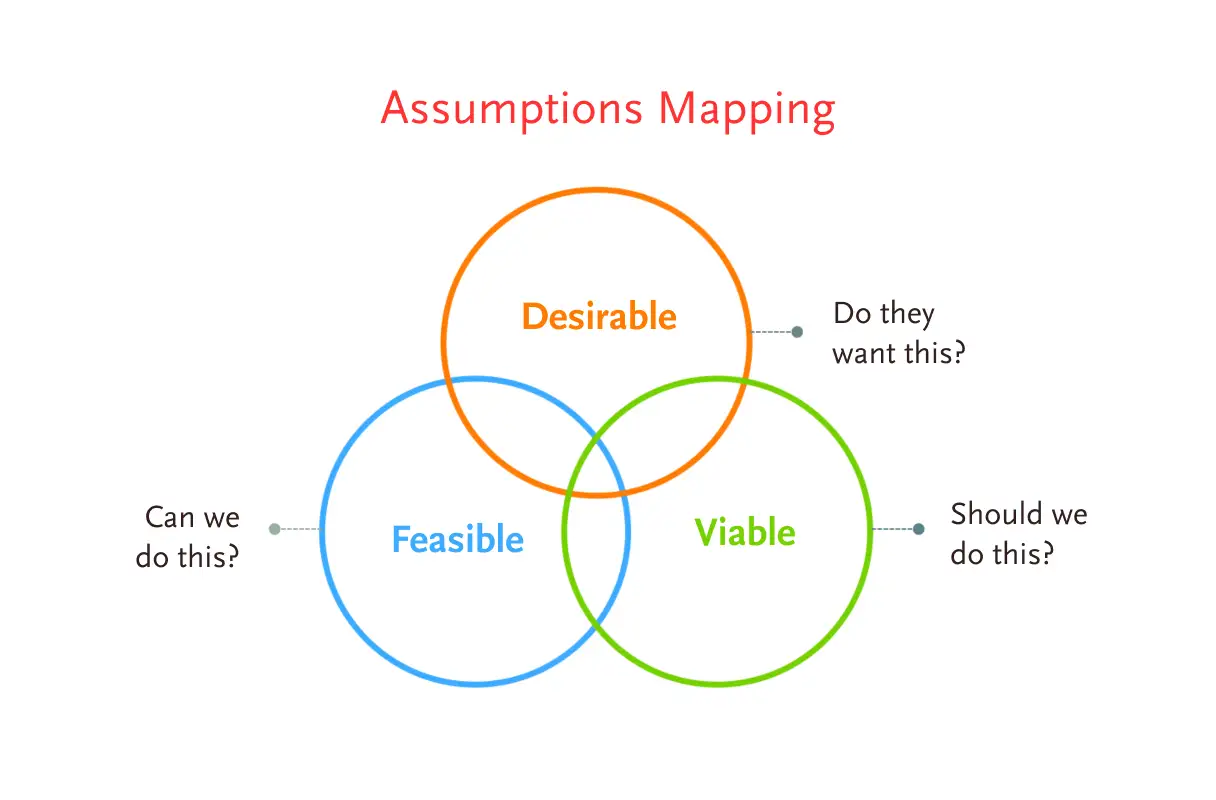

There are a few other assumptions to keep in mind. For example, you might have a great idea but not enough time to execute it, or maybe you have the time but not the resources. Sometimes an idea isn’t socially desirable or technically feasible, while in other cases it simply isn’t financially viable.

So consider all these factors before making a decision. In most cases, the product managers decide which idea they want to go forward with.

Once the idea is finalized, it’s time to create a user story and complement it with storyboards. For example, imagine you’re at the office when it starts raining. You take out your phone and open an app. The app shows your current location along with nearby cabs.

As you enter your destination, it shows how soon you can get a cab and how long the trip will take. You book the cab and a few minutes later you receive a notification: “Your cab has arrived.” You head downstairs, get into the cab, share the OTP with the driver, and your journey begins.

Now, there are generally two types of storyboards. One highlights the user’s emotional state within the context of the idea, while the other focuses on the specific solution you’re creating. If you have the time, you can create both.

5. Prototype

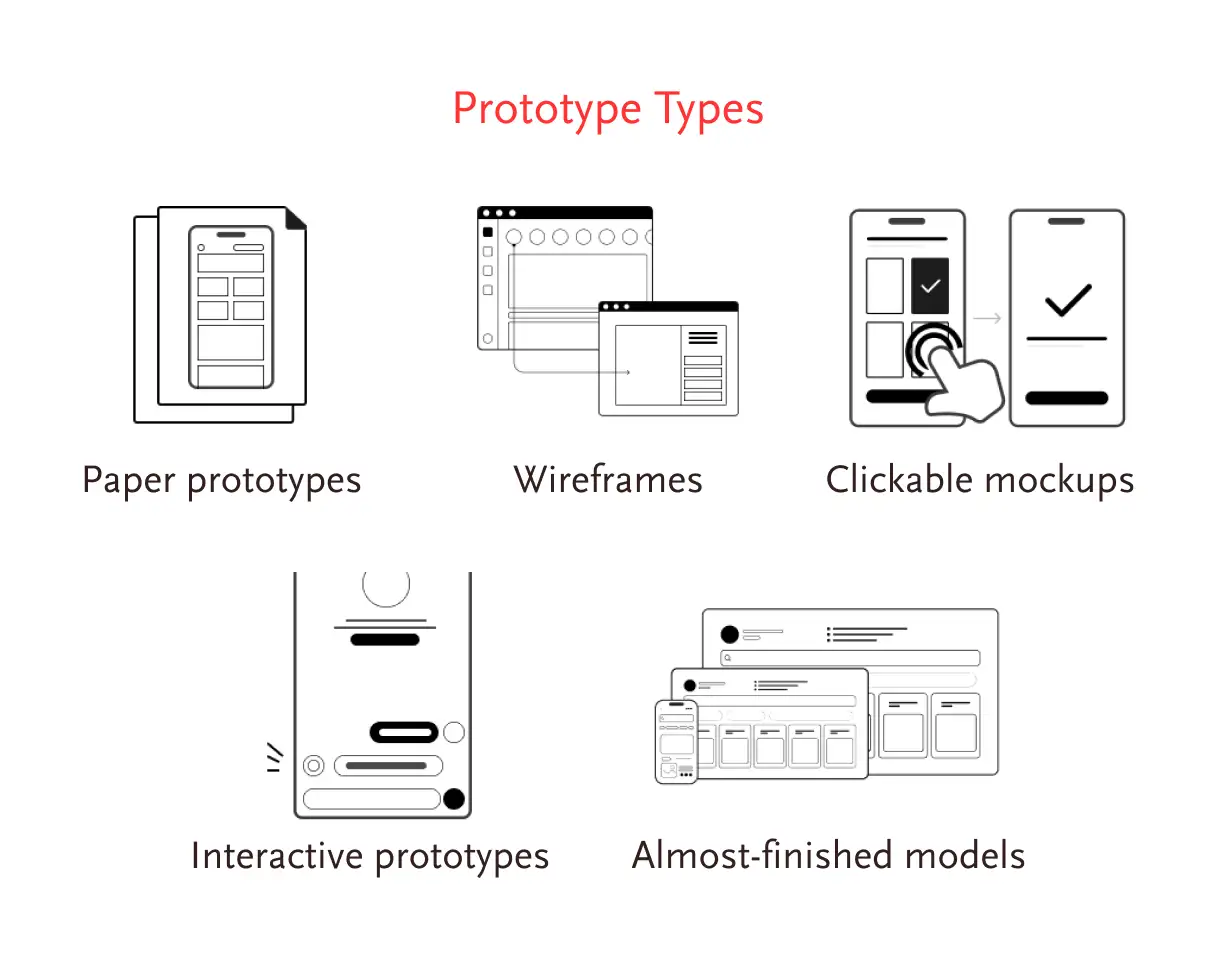

Now it’s time to create a working prototype based on your storyboards. While the goal isn’t to build a real product, the prototype should look and feel as realistic as possible. So use fonts, icons, and colors to make it visually appealing, create hotspots to make it clickable, and include transitions for a smooth flow.

And please don’t try to learn a new fancy prototyping tool at this time. Stick to the one you already know and feel comfortable with. Whatever you do, make sure your prototype should not look like something you have created in a hurry. Test users shouldn’t feel they’re interacting with a half-baked product— it should look polished and real.

While designers are busy working on the prototype, other participants can prepare for the Test phase by answering key questions:

- How will you recruit test participants?

- What questions will you ask them?

- How will you collect data?

- How many prototypes will you test?

You can choose to create either a single prototype or several variations with small tweaks to compare their performance. Once the prototype is ready, share it with stakeholders to ensure it aligns with expectations.

Finally, run through the prototype multiple times before testing with users. You don’t want to discover a broken interaction during the session.

6. Validate

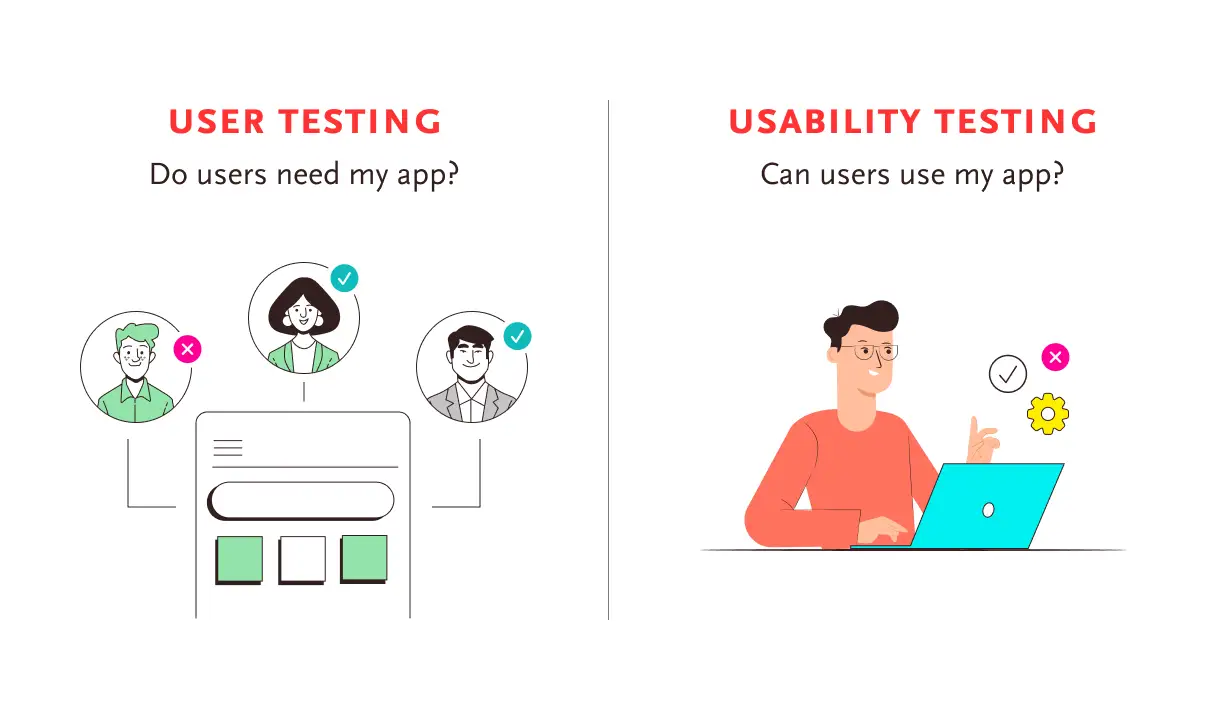

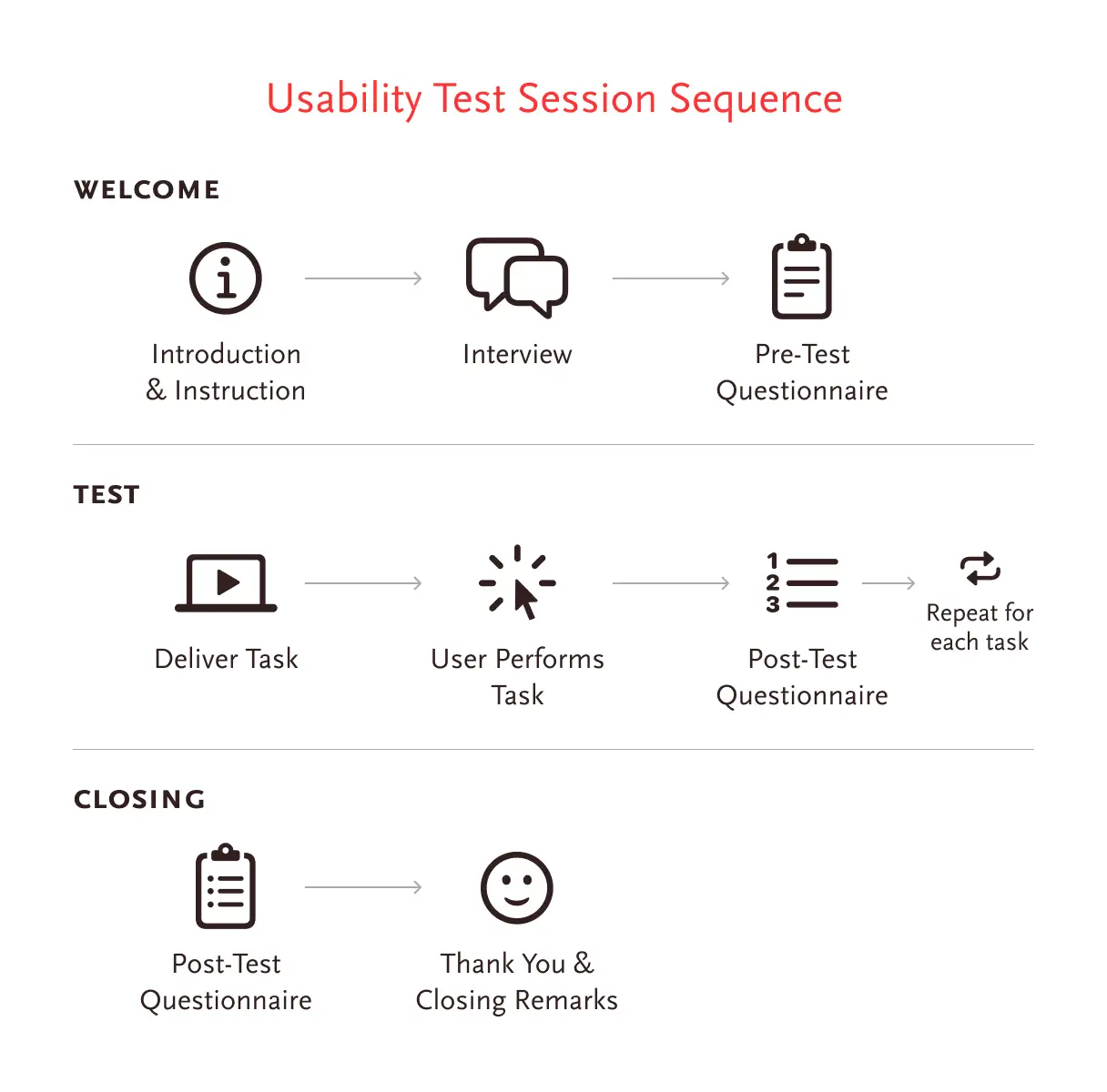

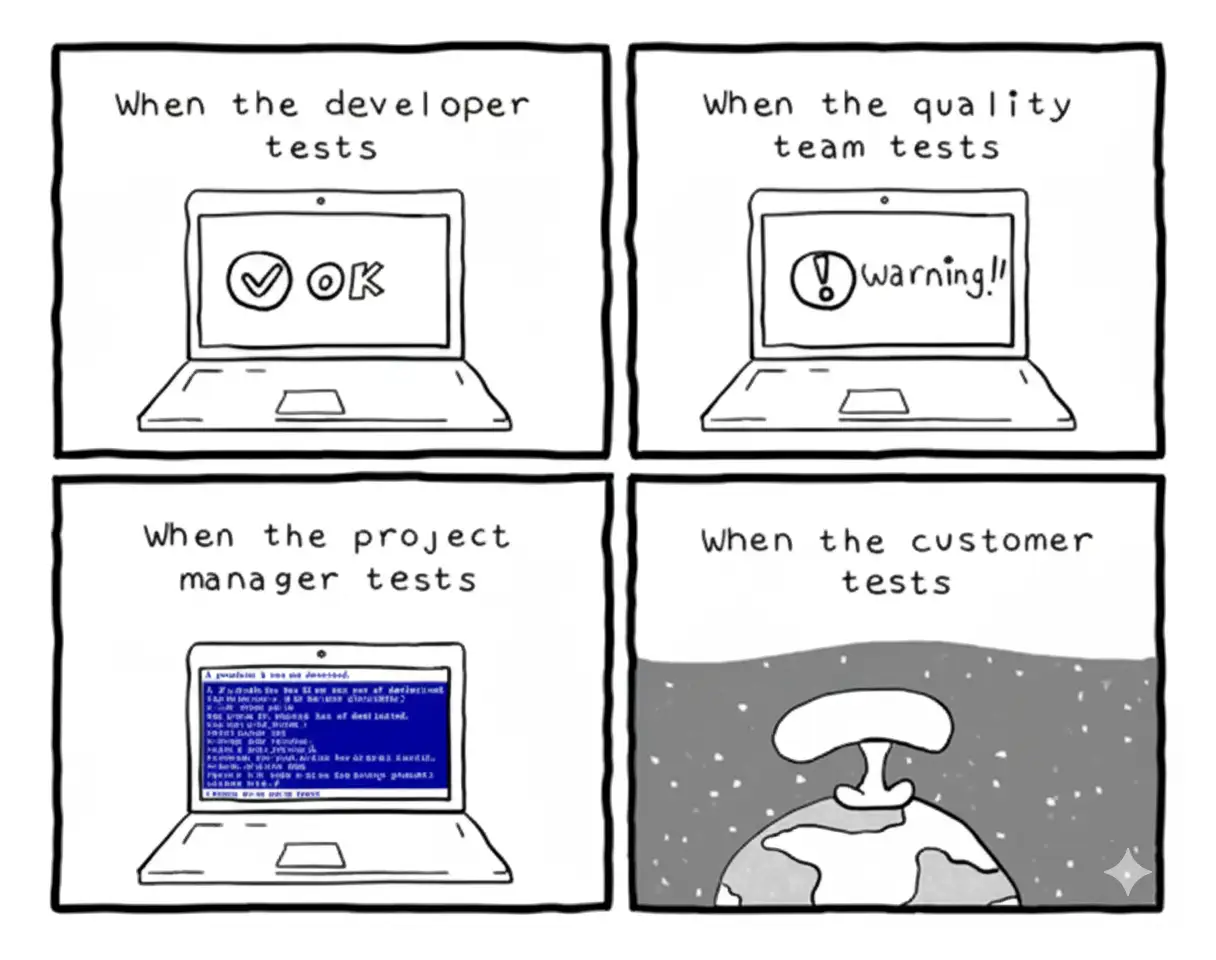

It is where you invite participants into your place, observe them use your prototype, ask them questions, and note down their answers. And to do this, usability testing is the industry’s go-to method. You don’t need a big crowd — five users are usually enough to uncover most of the issues.

But remember, our goal is not just to find usability issues but to validate whether we have created something valuable for users. Make sure to invite the entire team who were with you throughout the entire sprint to watch how participants react to the idea. Of course, don’t put them behind the user, they can watch it on a computer in another room.

After the users have interacted with your prototype, you can ask them questions to see what’s going on in their mind. Once you’ve collected all the insights, bring everyone together and discuss what stood out, what they learned, and what they want to improve in the prototype.

Conclude a Design Sprint

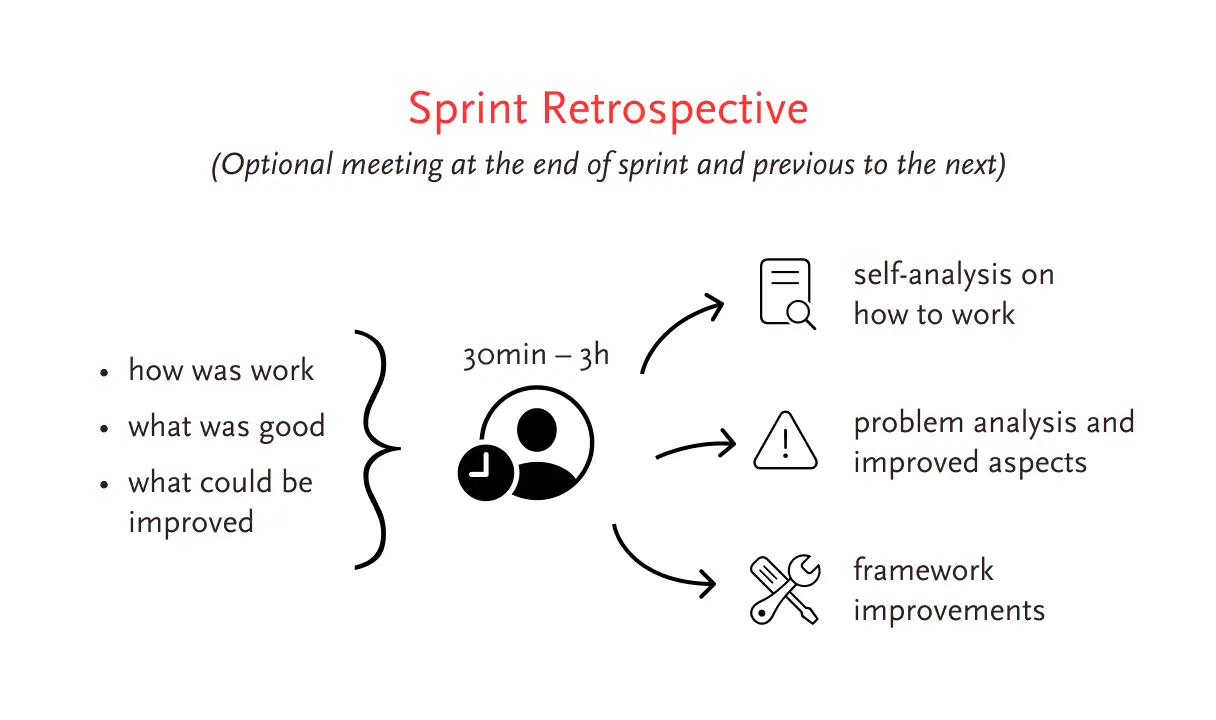

At the end of the day, all participants come together for a design sprint retrospective. A retrospective helps the team work better together and improve communication. There are mainly two questions to reflect on:

- What went well?

- What can we improve?

The team can then use the feedback to make the next sprint even more productive. A retrospective is not about shaming but empowering everyone.

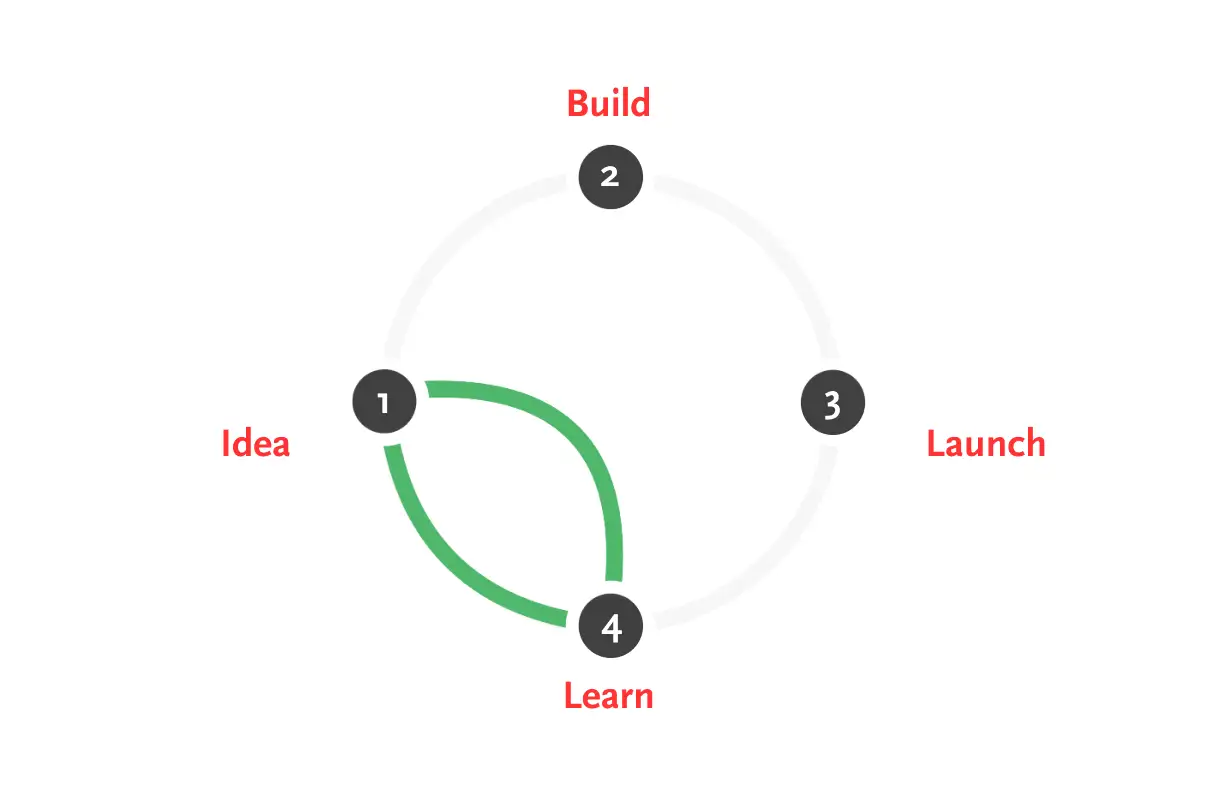

As Google puts it, there can be three possible outcomes of a sprint:

- Efficient Failure — Your idea did not work so well but you learned a lot in the process and saved valuable time by avoiding the wrong path.

- A Flawed Success — Some parts of the idea worked well, while others did not. This gives you insight on what can be improved and what to work on next.

- An Epic Win — The idea showed great promise and seemed to work well. You are ready to move into a more serious implementation phase.