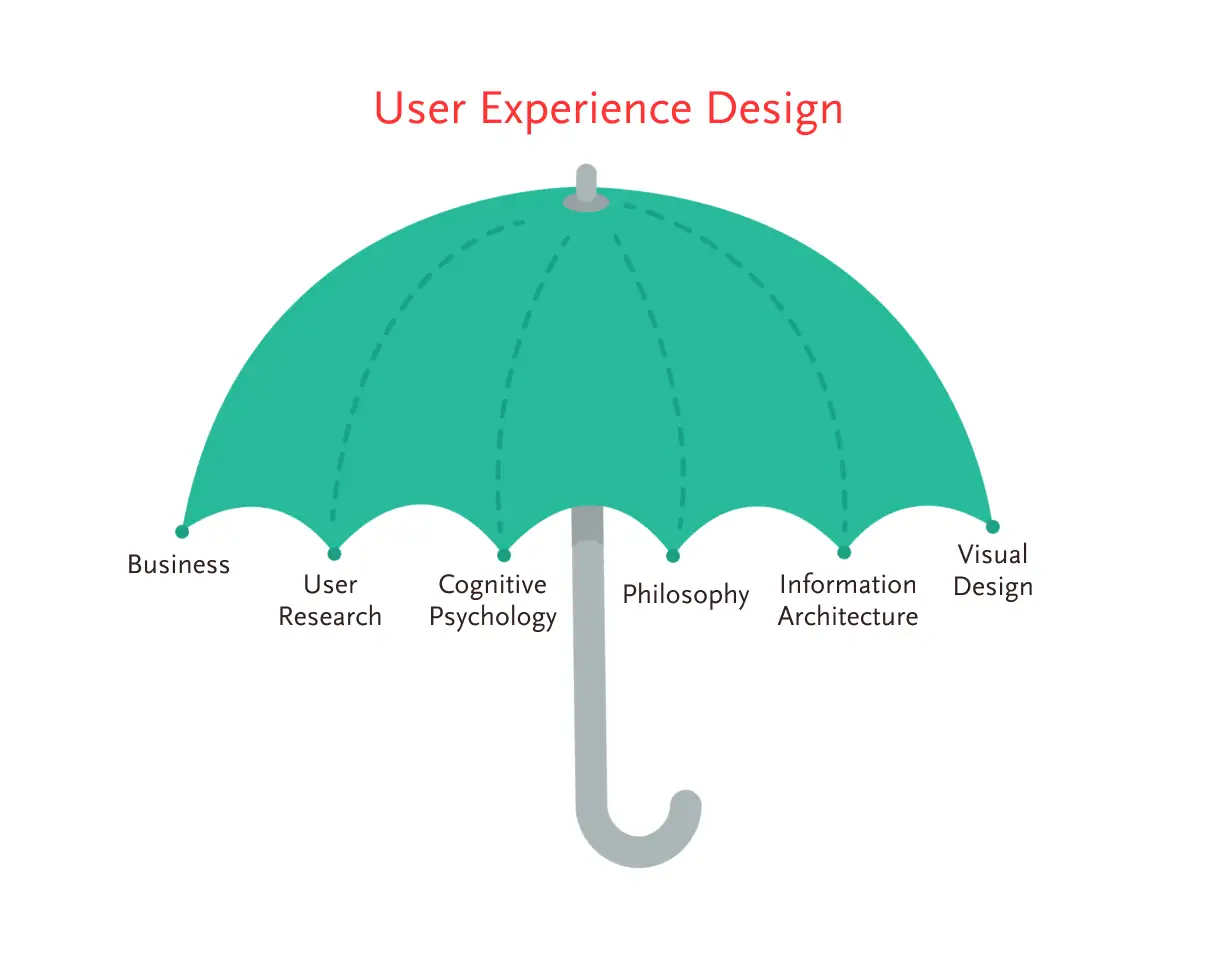

Earlier I talked about the characteristics, facets, and the components of UX. While the characteristics and facets help you recognize UX, components are what actually facilitate UX.

Now the question is how to arrange these components—business, user research, psychology, philosophy, information architecture, and visual design—in such a way that you can facilitate good—useful, usable, enjoyable, credible, findable, accessible, and valuable—UX.

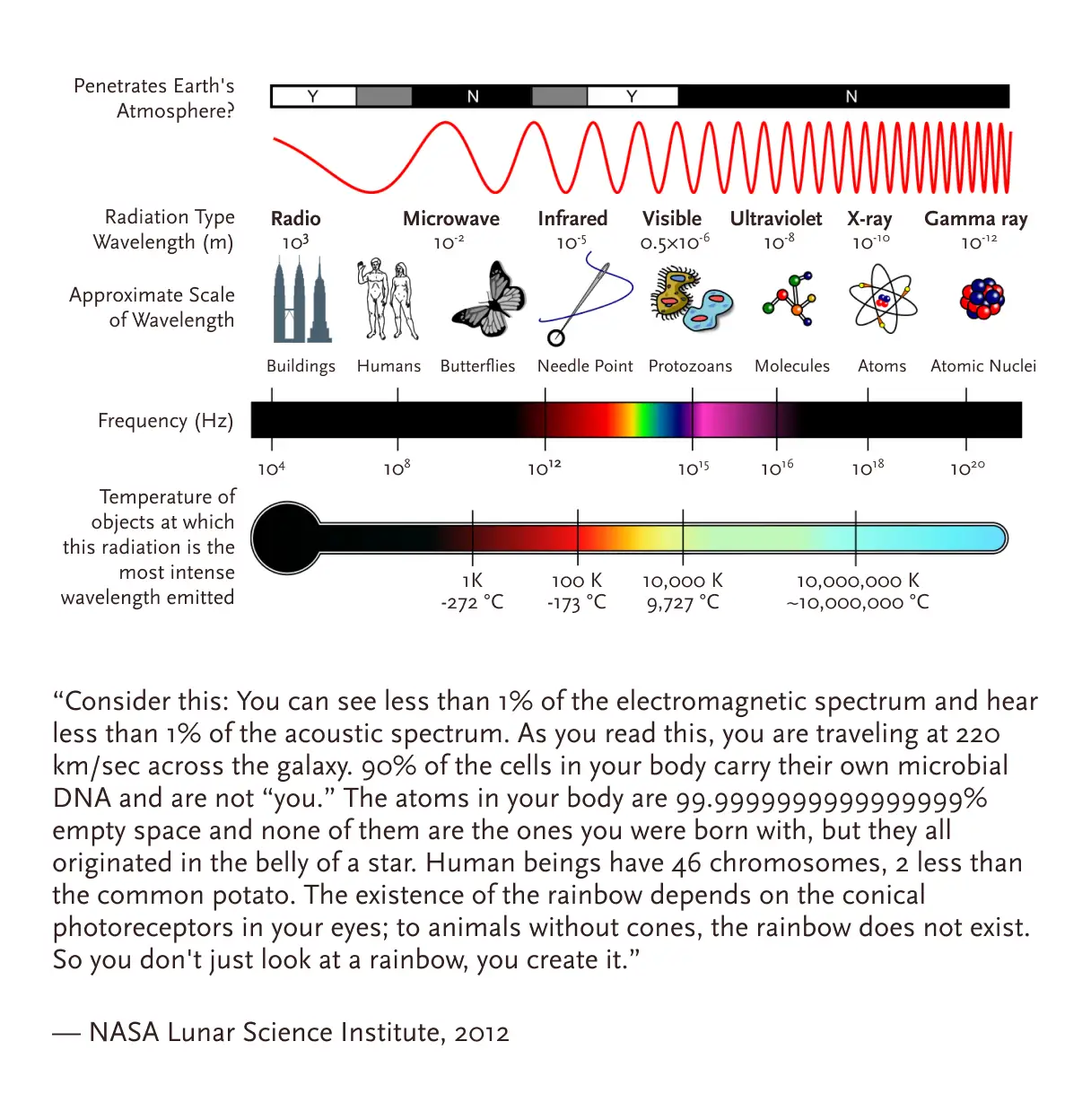

But why do you need to arrange them in the first place? To understand that, let’s take the example of your own body.

How To Build a Human

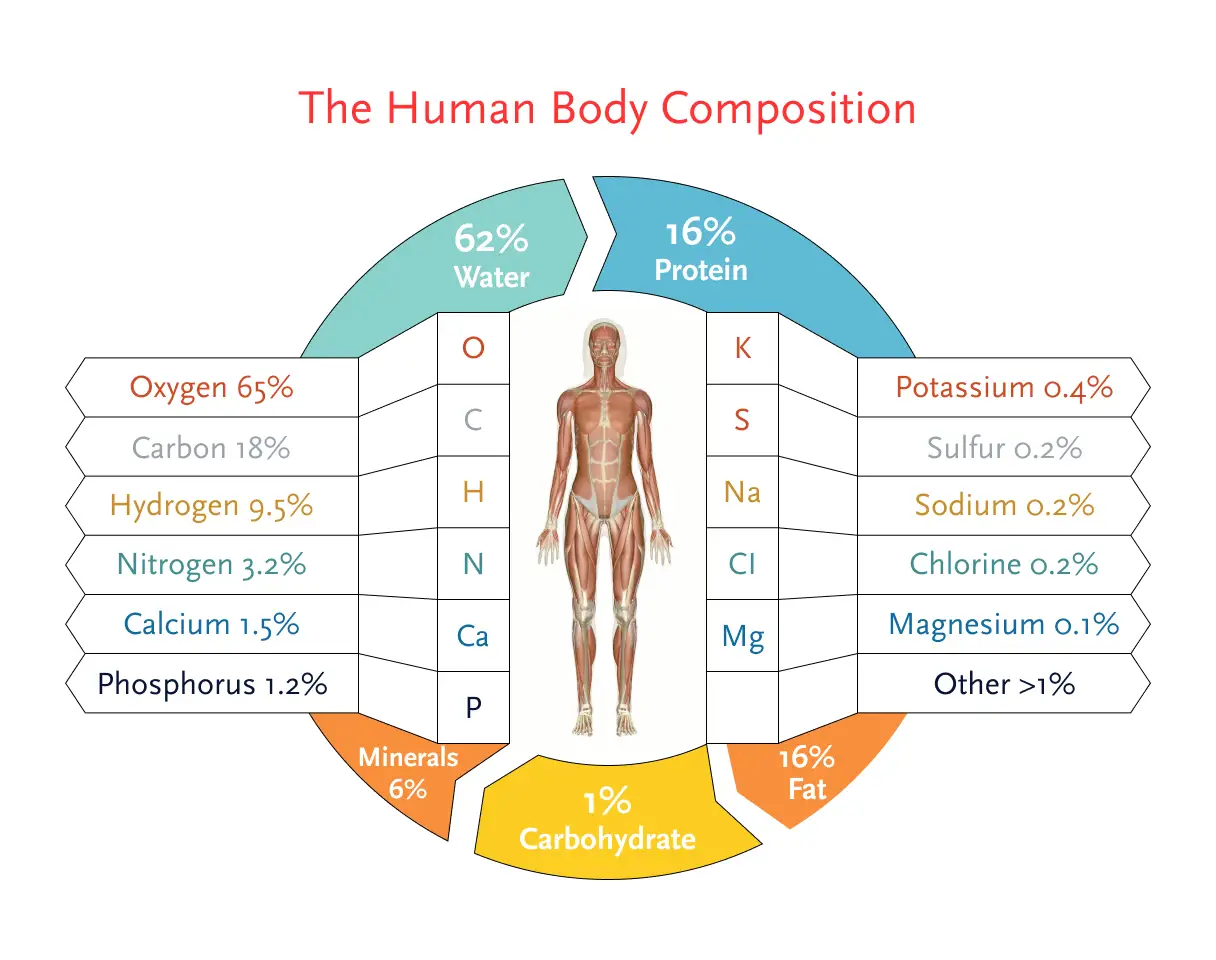

Just like UX has characteristics, facets, and components, so do you.

- You have physical characteristics such as height, weight, build; mental characteristics such as intelligence, memory, attention; and psychological characteristics such as happiness, fear, anger.

- You have mass, which is 99% made up of 6 elements: oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium, and phosphorus. About 0.85% is composed of another 5 elements: potassium, sulfur, sodium, chlorine, and magnesium. And the total mass of remaining elements is <0.01%.

You can see how these various elements are present in different proportions inside your body. And how your unique physical, mental, and psychological characteristics make you different from other human beings.

Similarly a lot of different elements or components facilitate UX. But only a few make the majority. And arranging these few elements in a logical manner is vital to building a product.

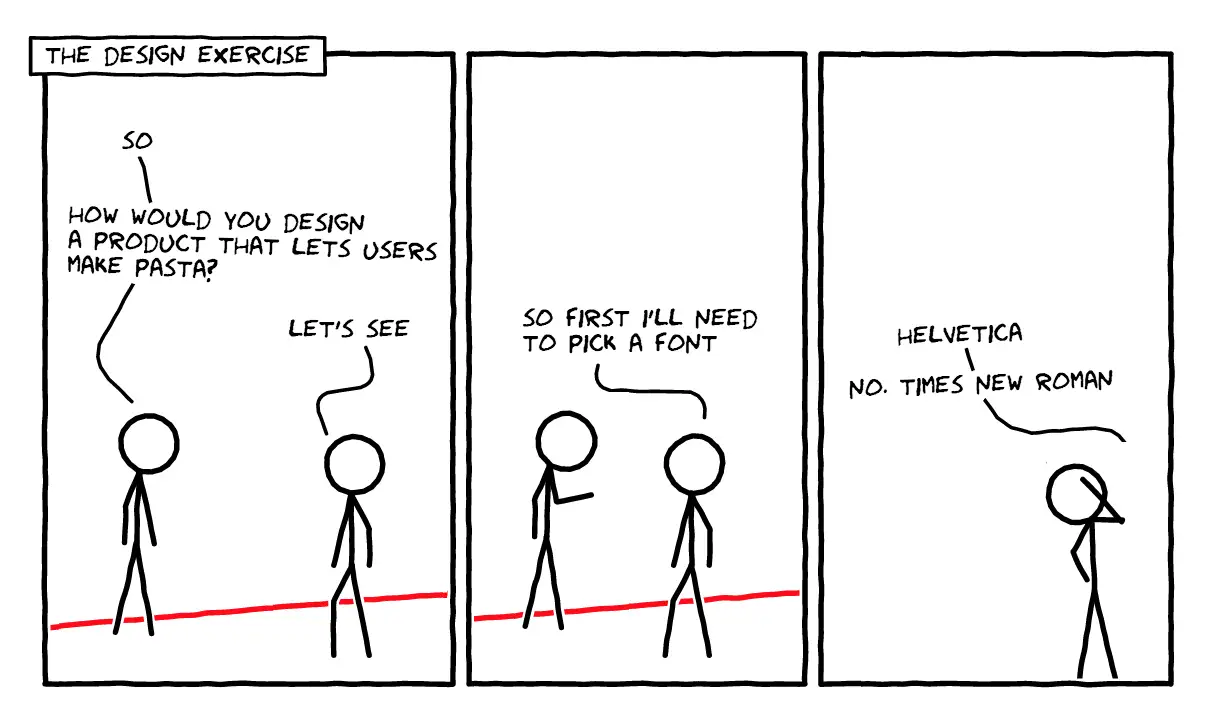

Okay, So Let’s Start With Visual Design

Well, if you want to build your product choosing the fonts or colors first, that’s your choice—but I’ll not recommend it.

Look, visual design is similar to a cherry on a cake. But there should be a cake first. So where is your cake? To bake one, you need a few ingredients that can play their respective roles in it such as

- Flour acting as the foundation

- Sugar for adding sweetness

- Eggs for binding ingredients

- Butter for providing richness

- Baking powder for leavening

- Milk for adding moisture

- Vanilla for enhancing flavor

- Salt for balancing sweetness

Now, all these ingredients are great, but without a recipe—step-by-step instructions—you can’t bake a good cake. You must know the precise amount of ingredients, their order in the recipe, and the actions you have to take on them to make something good.

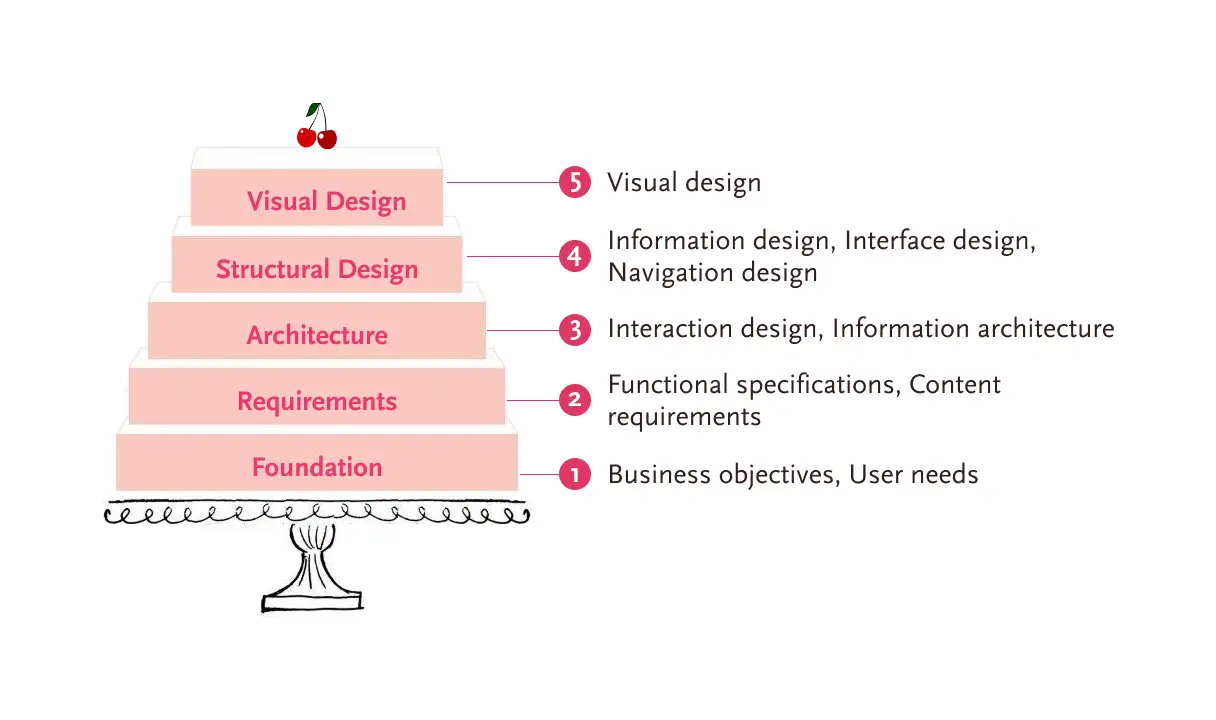

The Elements of UX is that recipe. It tells you all the necessary UX elements as well as their precise order required to build a good product. Let’s see what these elements are.

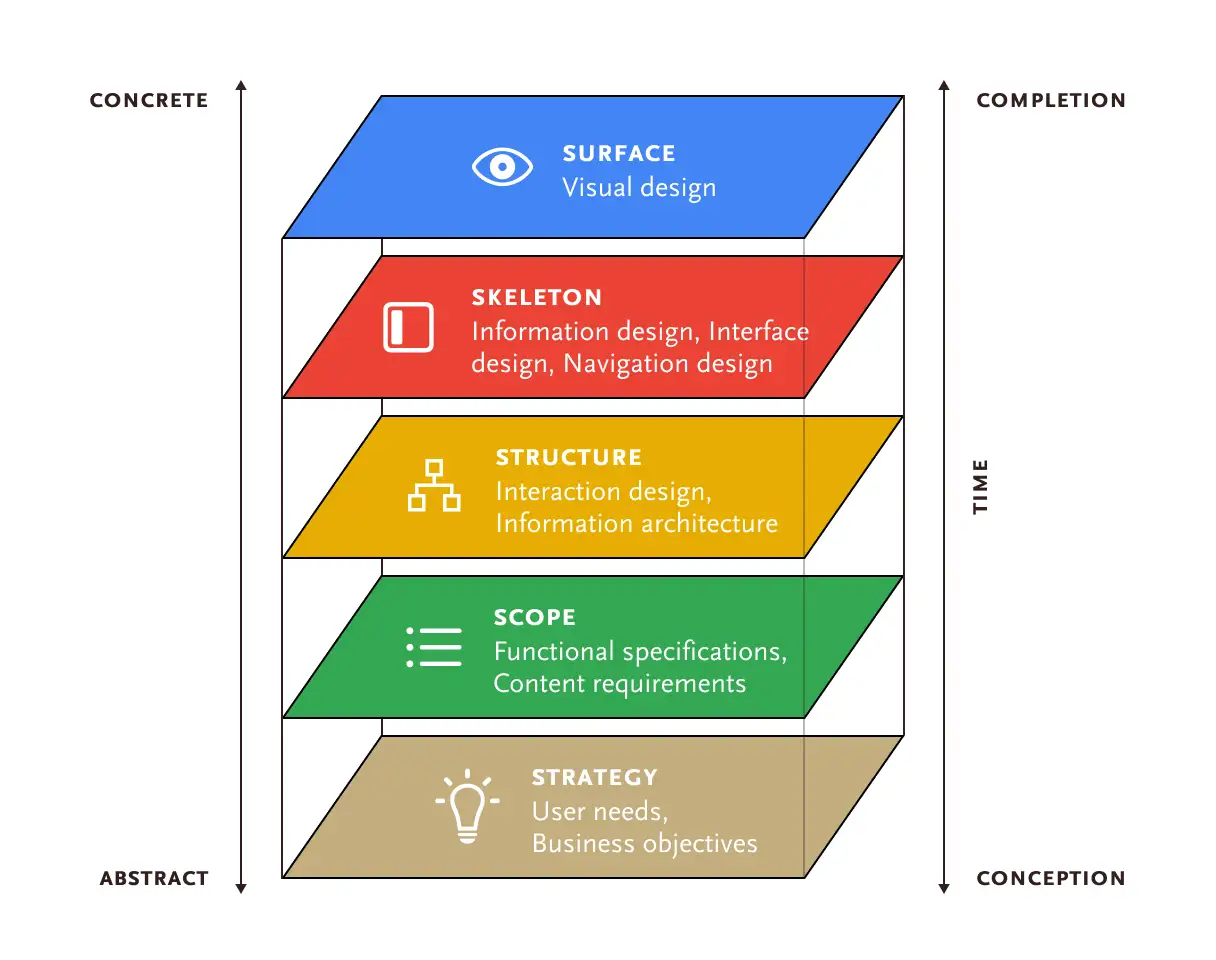

The 5 Planes

The Elements of UX is a framework introduced by Jesse James Garrett, the Adaptive Path guy. He is another well-known figure from the same era as Peter Moreville, Jeffery Zeldman, Eric Mayer, and others. And although it’s an old framework created specifically for websites, it still applies to digital products whether it’s apps or websites or anything in between.

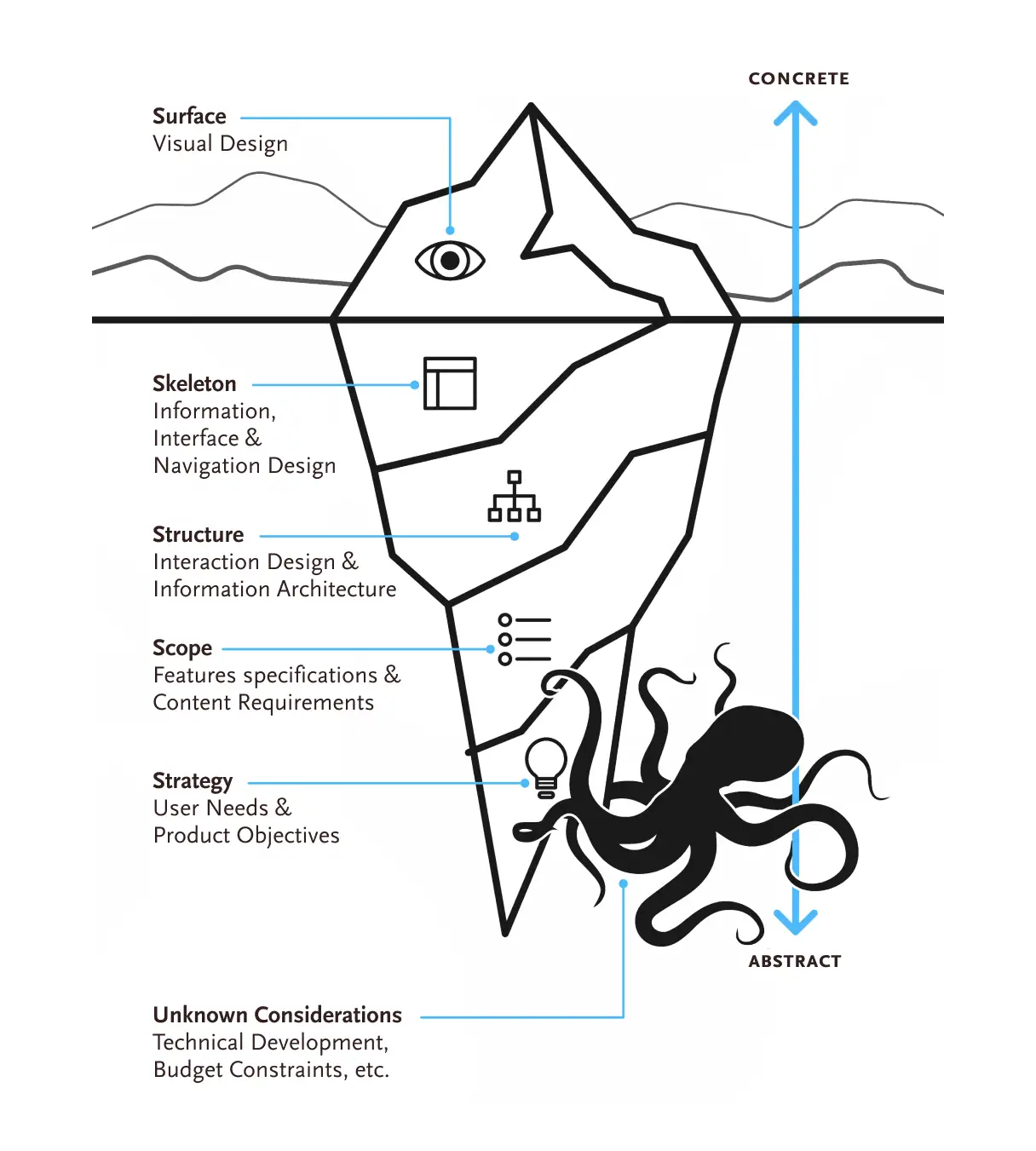

The framework has 5 planes—Strategy, Scope, Structure, Skeleton, and Surface—stacked from bottom to top. Your product starts its journey from the bottom i.e. conception stage where you have abstract ideas about what to build. But as you move upwards, the picture becomes clearer and your product starts to take shape. Finally, when you reach the top i.e. completion stage, you have a concrete product in your hand.

Okay. So let’s start with the first plane, Strategy.

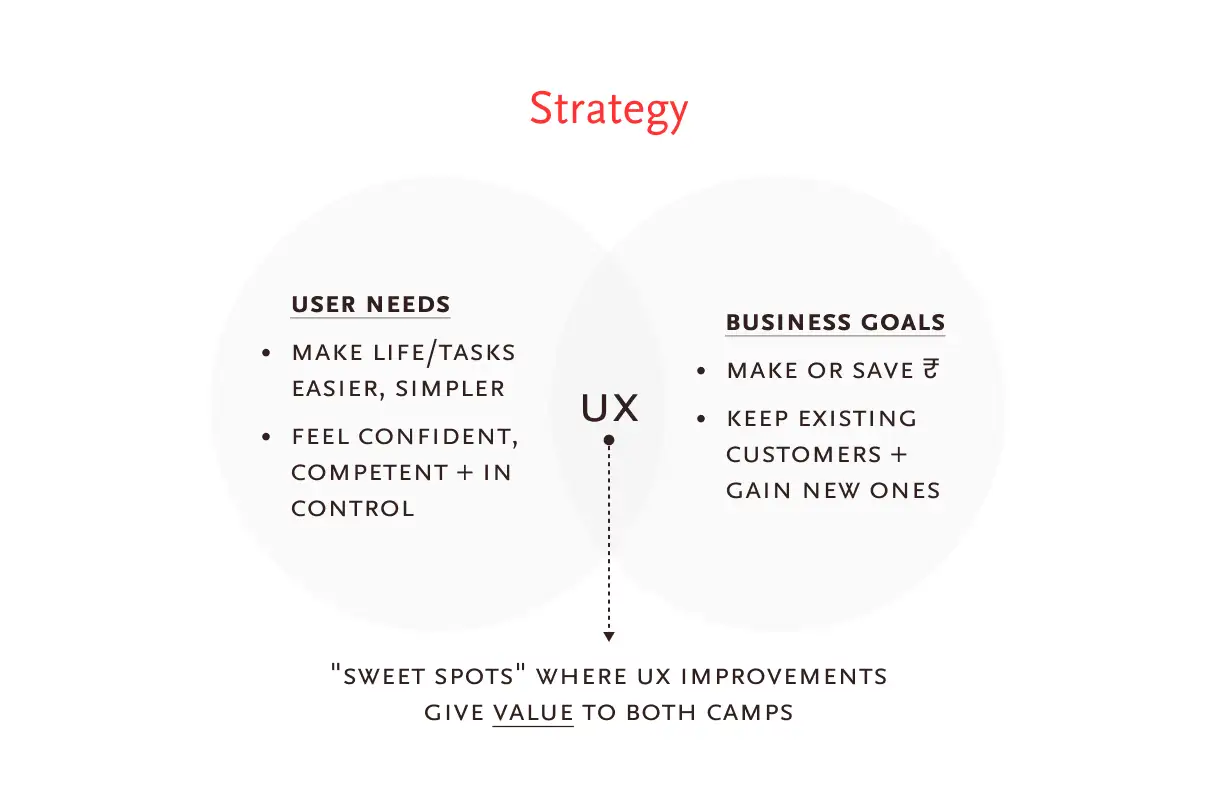

Strategy

Every project starts with a strategy. Here the founders, C‑suite executives, or product managers put their heads together to do some high-level thinking and try to answer a few fundamental questions—specifically, two:

- What are the site (business) objectives?

- What are the user needs?

Perhaps the most important business objective—sometimes the only one—is to earn money. And it’s not a bad thing unless you don’t provide any value to people or compete fairly in the market. Even NGOs want to attract donors to support their cause.

But a business can only earn when it provides something valuable in return. This value could be either:

- Solving users’ pain points

- Fulfilling their desires

- Meeting their needs

How much money a business can make depends on how much value it can create. For example, on Amazon, you can find a lot of products, order them, compare them, and return them at any time as compared to a mom-and-pop store. And that’s what makes Amazon so much valuable.

Now, you don’t need an exact step-by-step process at this time but you should definitely have answers to a few big fundamental questions such as:

- What are people’s pain points, desires, or needs?

- Are they really worth solving?

- Can you make a business around it?

- What resources would be needed to build a solution?

- How is your product going to be different from others?

Be your own devil’s advocate to thoroughly examine your answers. Look, Strategy is the bottommost plane, and every choice you make here is going to affect top layers. These questions are the foundational stones upon which you’ll build your entire product. And you don’t want to move the foundation after you have already built two floors—do you?

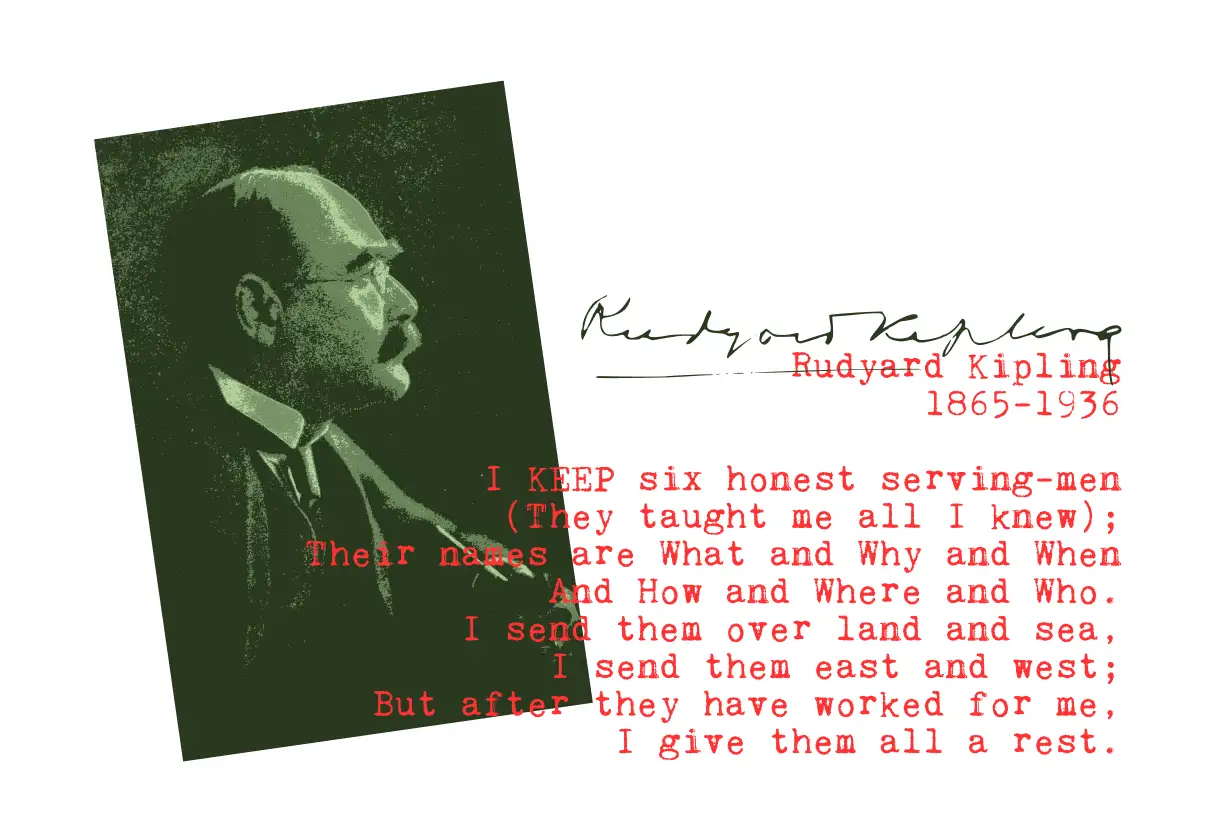

But there are also times when you aren’t sure about the answers so you tackle these questions as they come by. But there is a framework called “The 5W1H, also known as the Kipling method” that you can use whenever you feel lost and want to reach the bottom of a situation.

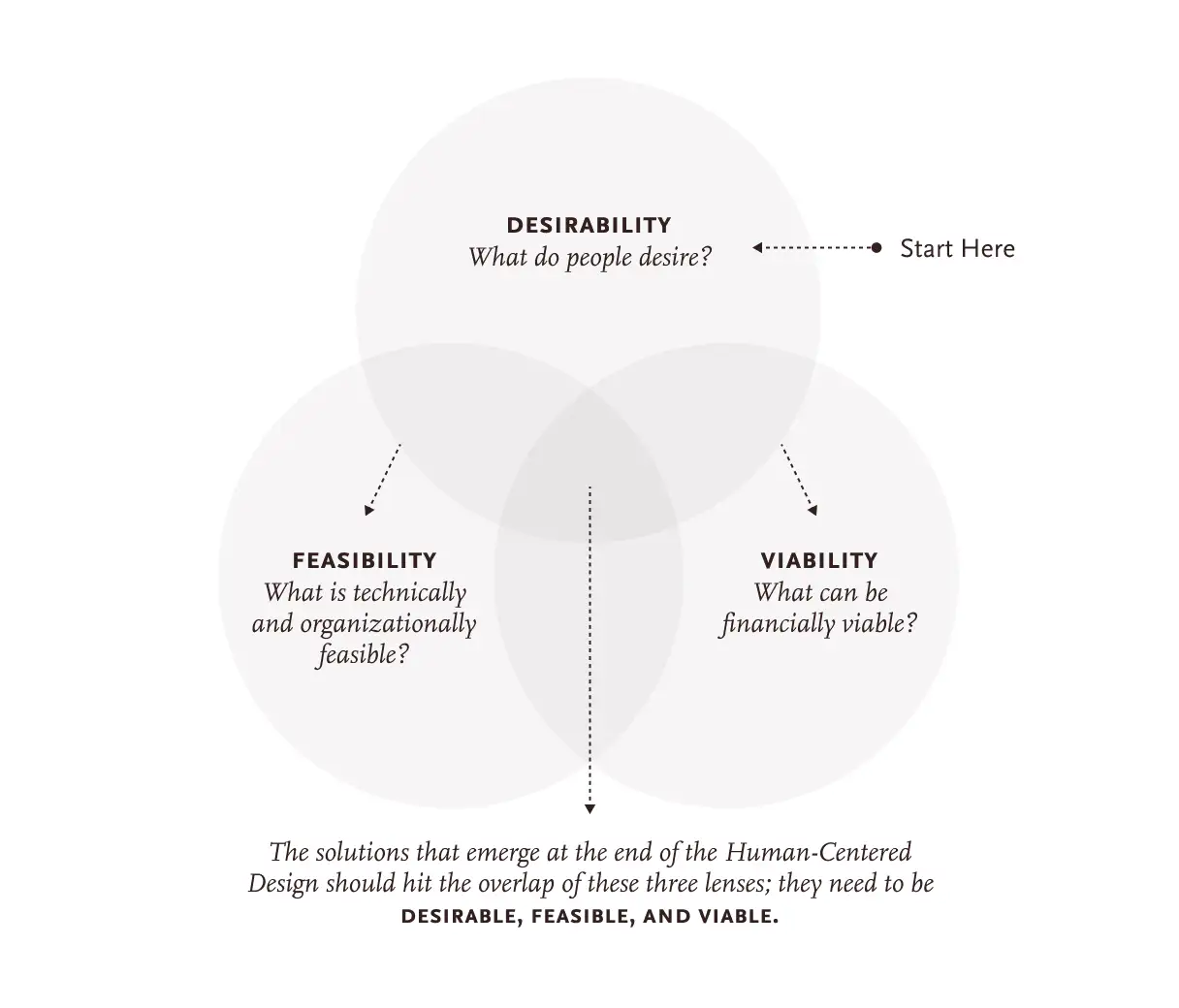

Once you have zeroed in on your ideas, you can use IDEO’s DVF Framework to look at how good they are. are. According to this, for a product to become successful, it should be highly desirable, economically viable and technically feasible. And even among that, desirability should be your number one goal because if people don’t desire your product, then the other two factors don’t even come into play.

For example, let’s say you’re in college. Would you be interested in knowing who’s single, and who is seeing whom there? Yeah, I think so. That’s what made Facebook desirable for those early college-going students—and later, to the entire world.

There is also an extended version of the IDEO’s DVF Framework. It has been shared by Anil Swarup, a retired IAS officer at Raj Shamani’s podcast. He said, for an idea to work it has to be

- politically acceptable,

- socially desirable,

- technologically feasible,

- financially viable,

- administratively doable,

- judicially tenable,

- emotionally relatable, and

- environmentally sustainable

Once you’re happy with the result, move to the next plane called Scope.

Scope

Even if your solution passes all the tests with flying colors, you shouldn’t start building it immediately. Why? Because, theoretically every idea is technically feasible if you have unlimited time and money. But since you don’t have unlimited resources—and most likely have only one shot at making it big—you must tread carefully.

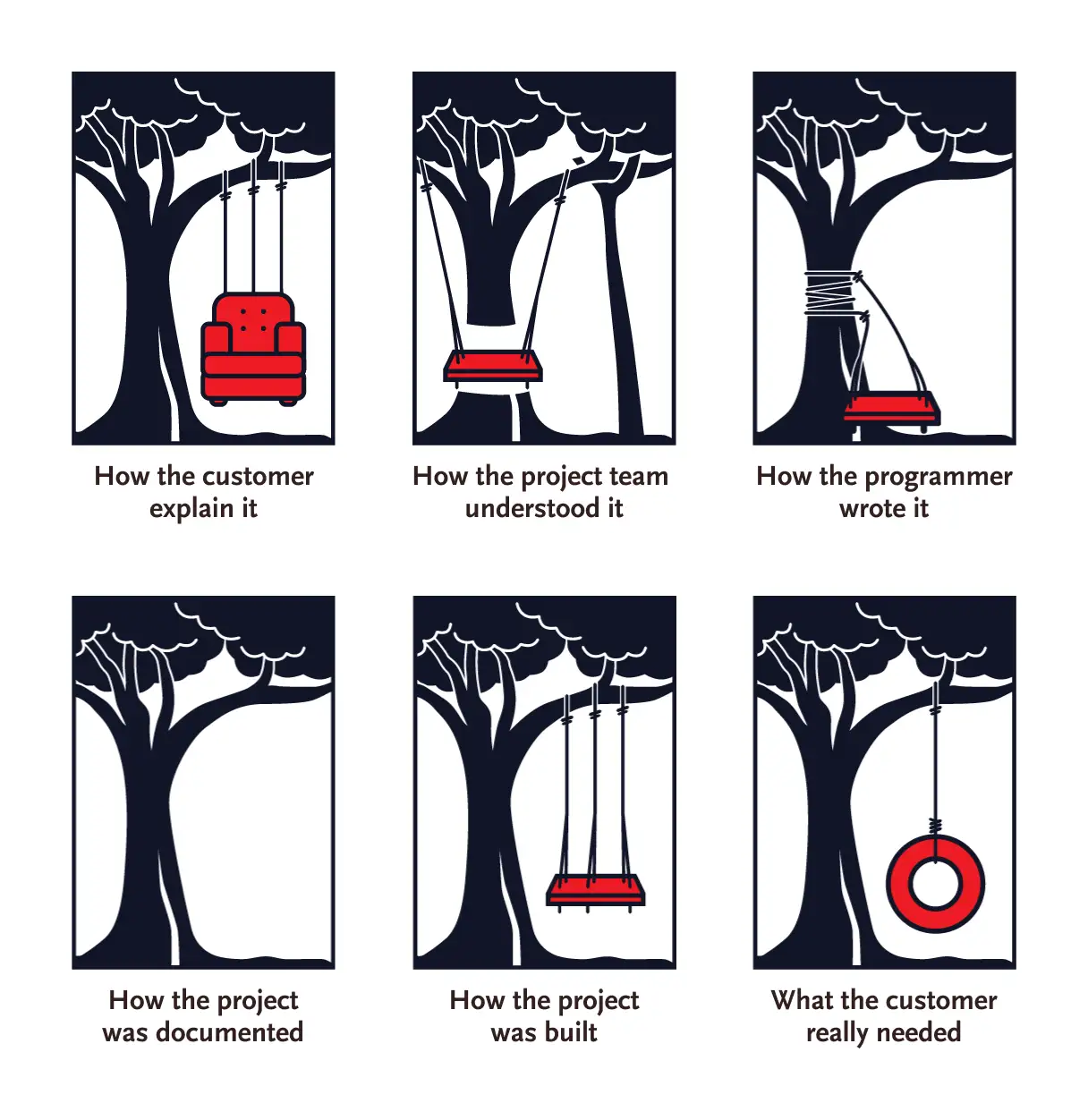

So how do you decide the Scope of a product? Typically founders or product managers do their own research at this point and sit together with engineers to decide what features they should build first.

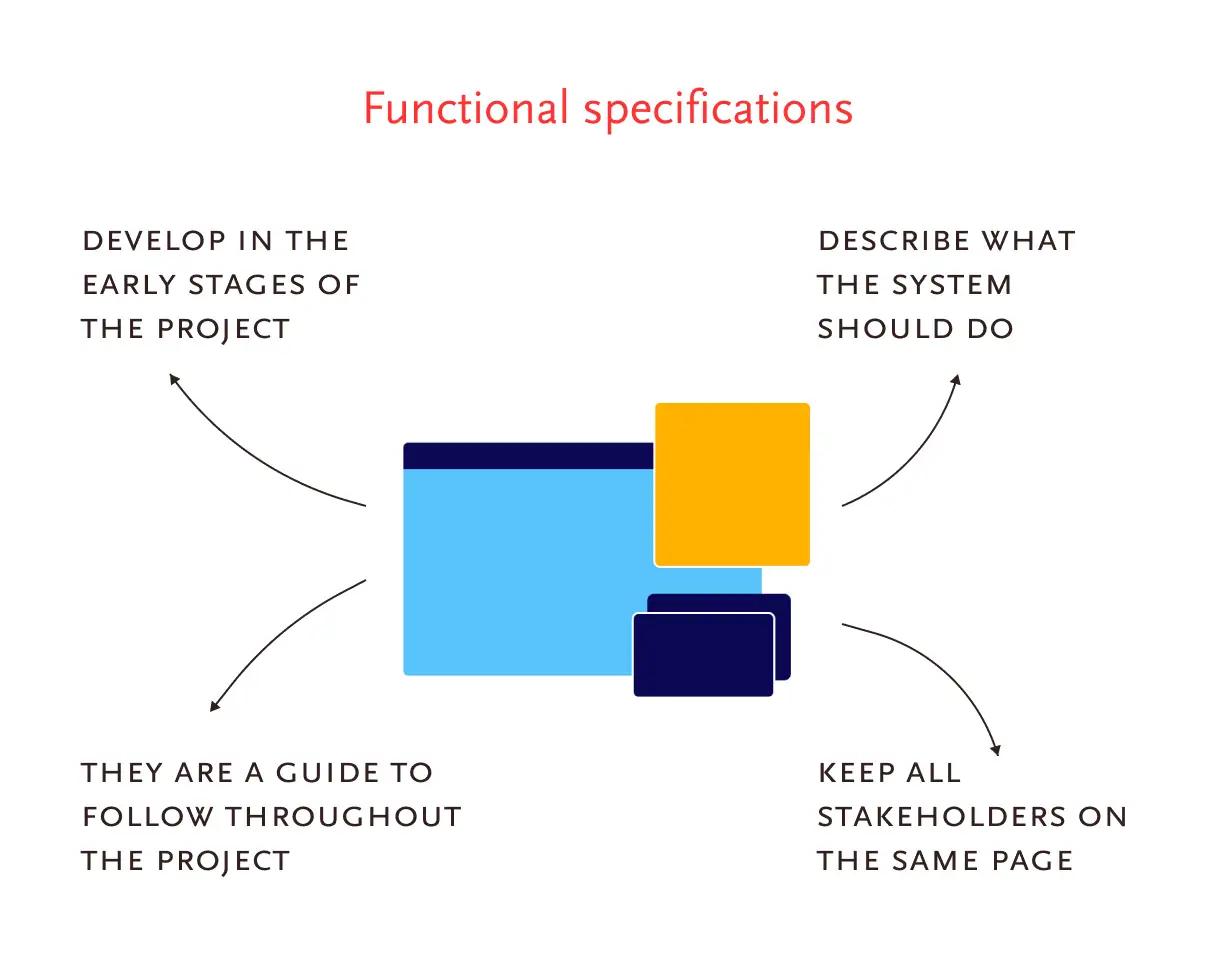

Primarily you define two things here:

- Functional specifications, and

- Content requirements

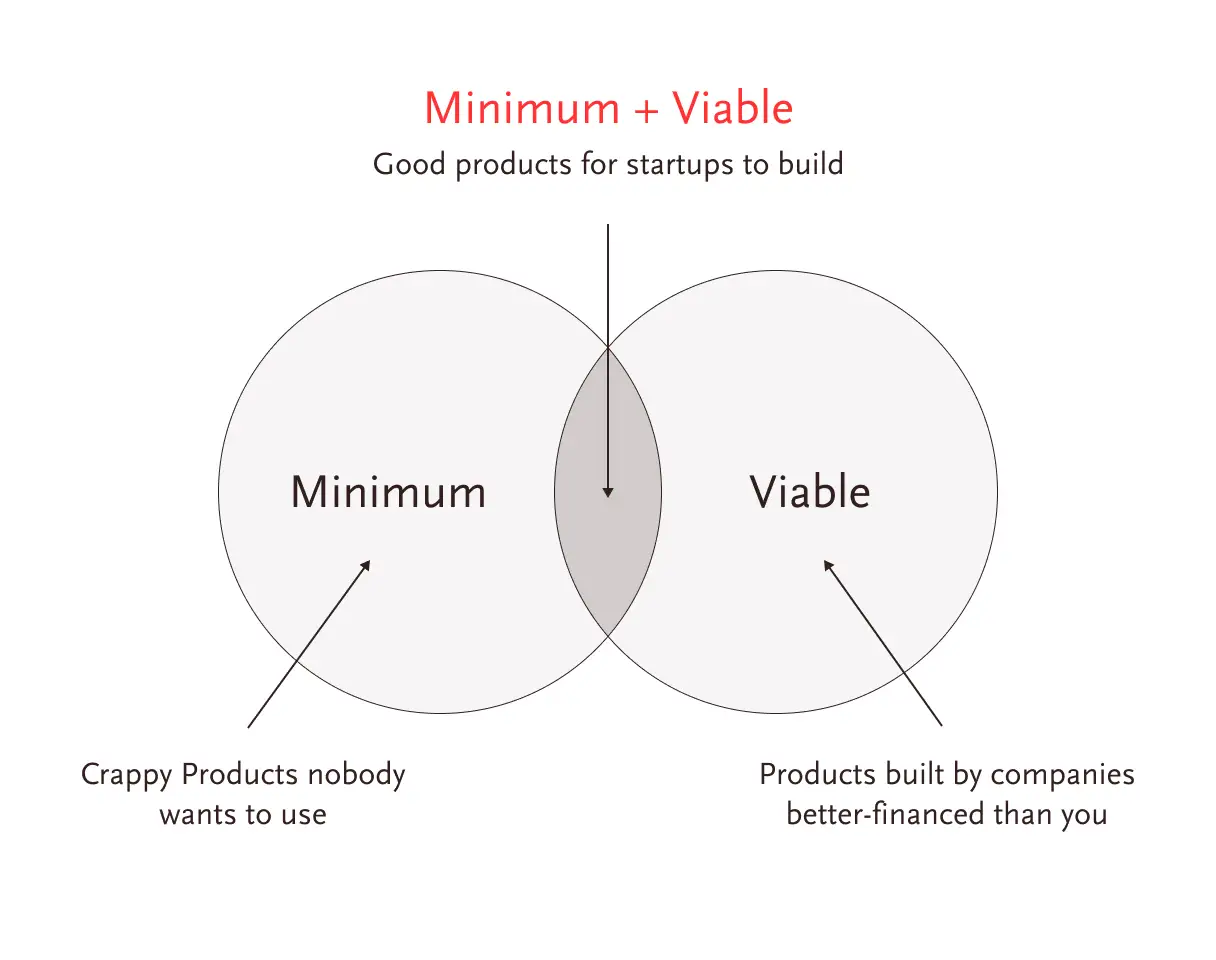

On the functionality side, you decide which specific features you must include in your product to meet user needs. No matter how brilliant your idea sounds or how much validation you got under your belt, you don’t want to build the entire solution all at once.

Ideally, you want to build a product for a very specific audience, with a few core features that you think they cannot live without (and hopefully pay you money for using them). It’s called a Minimum Viable Product (MVP).

For example, WhatsApp started with chat only. And later added other features such as media sharing, audio/video call, voice messages, and money transfers.

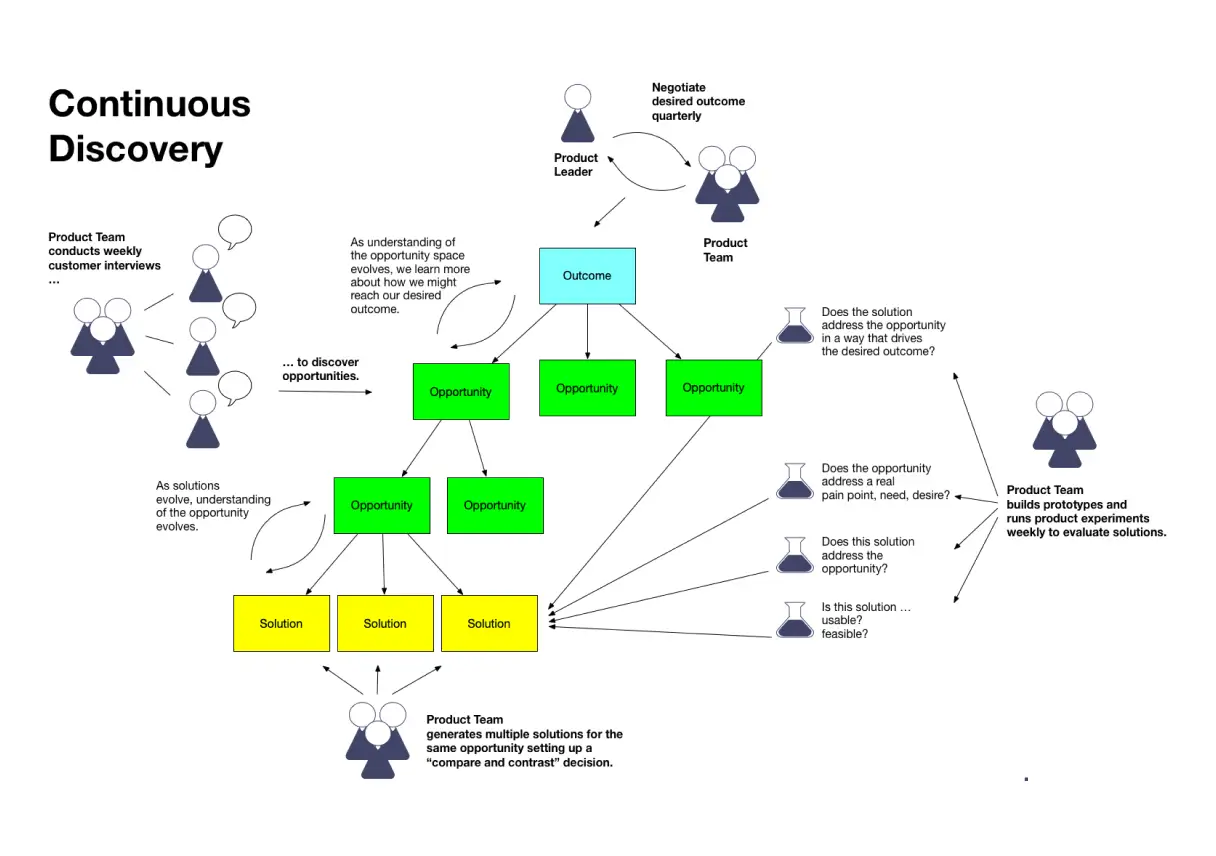

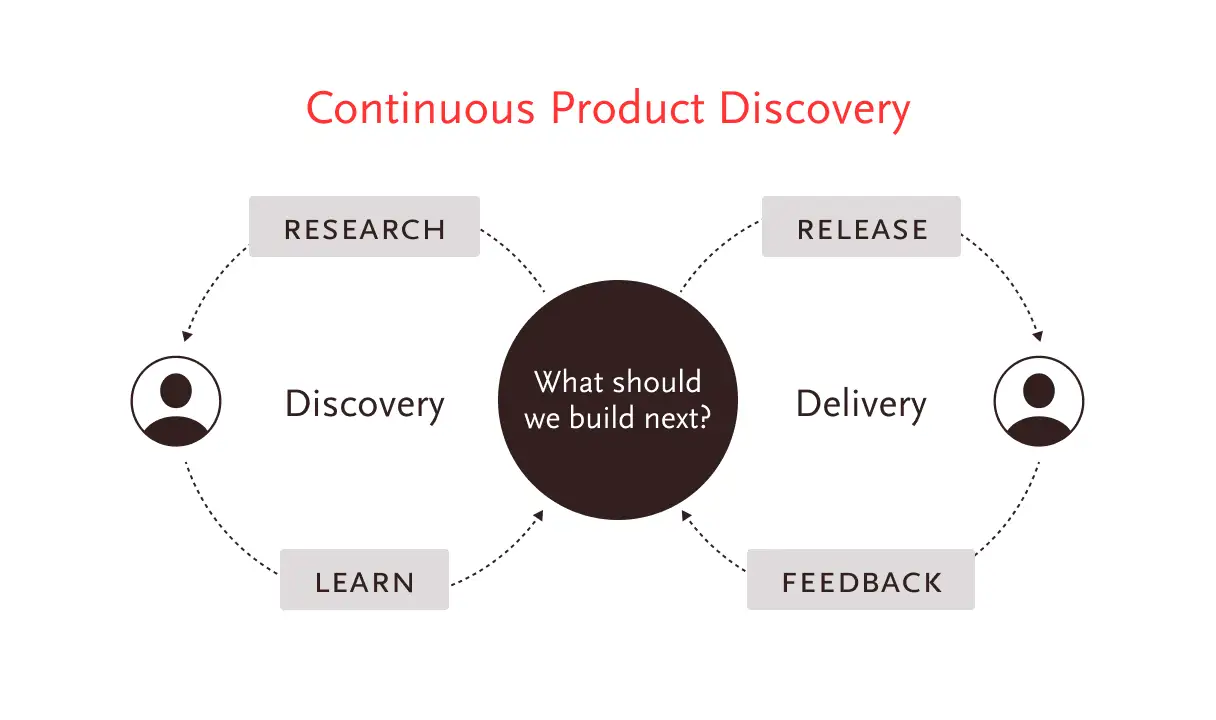

Also, make sure to take users’ feedback throughout the product life cycle and continuously improve your product—a practice Teresa Torres calls “continuous product discovery.”

Now, along with functionality, you also have to figure out the content requirements at this stage, such as:

- Who would write, update, or approve the content?

- Would you use a CMS or build your own system?

- How would you collect, manage, and discard the data?

Once you freeze the functionality and content requirements of your product, you can move upwards to the third plane, Structure.

Structure

At the Structure plane, a product comes out from the discovery or high-level thinking stage (not completely) and starts moving towards the delivery stage. When the Scope is set (not in stone), you start to lay out your product structure, and here two components help you out:

- Interaction design, and

- Information architecture

This is the first time you actually get your hands dirty and your product begins to take shape. For example, let’s say at the Scope, you have decided to build a chat feature but here you actually create the entire flow and define how the user interacts with the product.

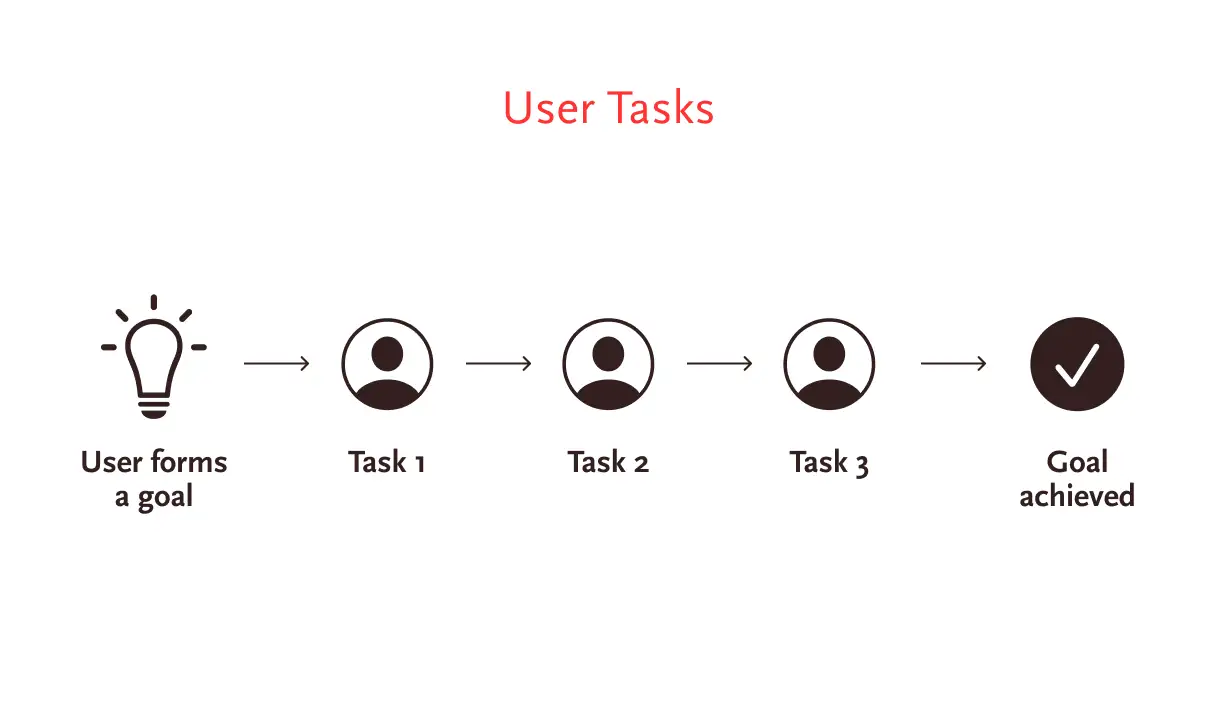

For example, you tap the app icon to open it, go through onboarding, and tap skip to land on the chat screen. Then you tap on an individual chat to go inside and find the chat bar at bottom. As you touch the chat bar, a keyboard pops out. You type a text and click the arrow to send it.

This is an example of a user task showing how a user can send a text message to an individual. And there could be hundreds of such user tasks in a product. Your job is to build them, check their interrelationship, identify potential bottlenecks, and assess their impact on user satisfaction.

Now let’s talk about information architecture. Just like an architect optimizes physical space to make it pleasurable to people, an information architect organizes digital space in such a way that it looks clearly noticeable, easily recognizable, and highly scannable. There are different ways you can reduce the complexity in a product such as using

- Progressive enhancement

- Unbundling products

- User segmentation

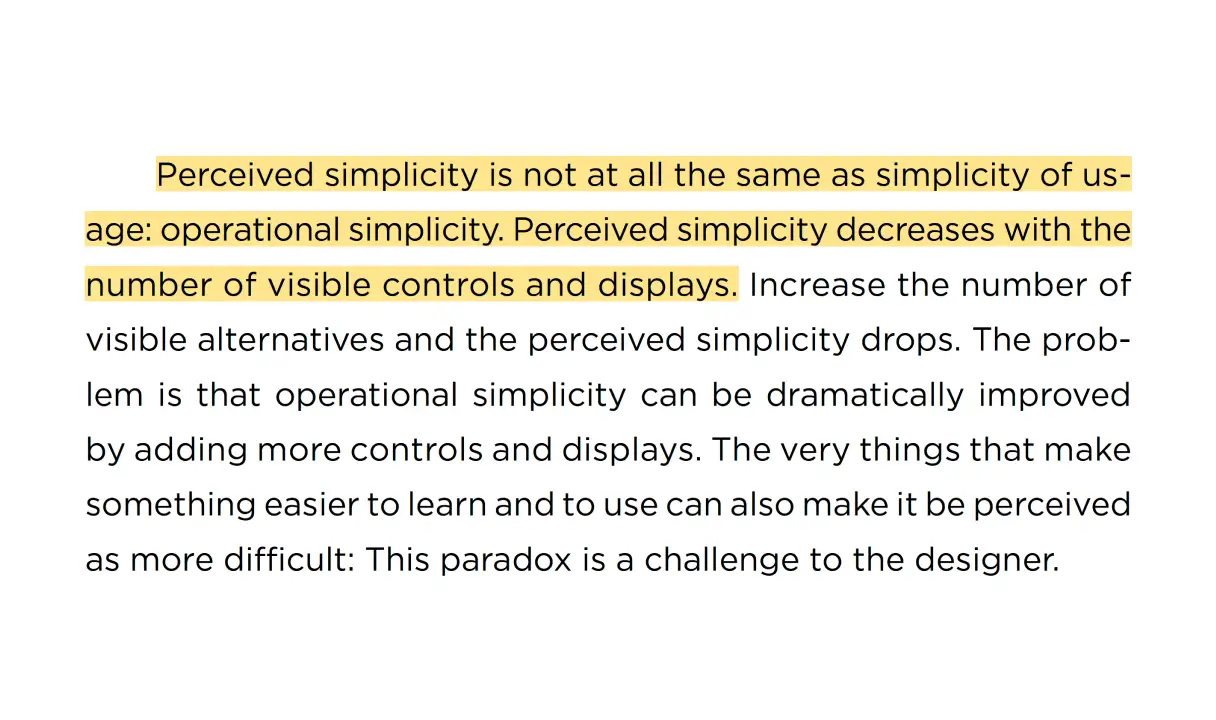

I love the WhatsApp approach where it uses a concept called “perceived simplicity.” Although it has powerful features such as audio/video call, send/receive money, and voice messages along with all the typical bells and whistles, even then it doesn’t look complex. You can’t feel their presence when you’re chatting with someone but they’re there when you need them.

Skeleton

Skeleton is where you create the bare bones of your product. It’s the fourth and only plane where you deal with three different components:

- Information design

- Interface design, and

- Navigation design

Let’s begin with information design to see how it contributes to creating the skeleton of a product.

Information design follows the visual design principles, popular metaphors and conventions to make the information more engaging and clear. For example, products usually put their logo on the top-left corner because the English language is read and written left to right and top to bottom. It naturally makes the top-left position the most important area of a page. And what would be more important than putting your logo there?

Also, don’t you wonder why products still use a floppy disk to represent “Save”? Or why does an hourglass still represent loading? The reason is that we’ve been using these objects for a long time to symbolize such actions. Over time, people have become so used to them that they’ve turned into conventions.

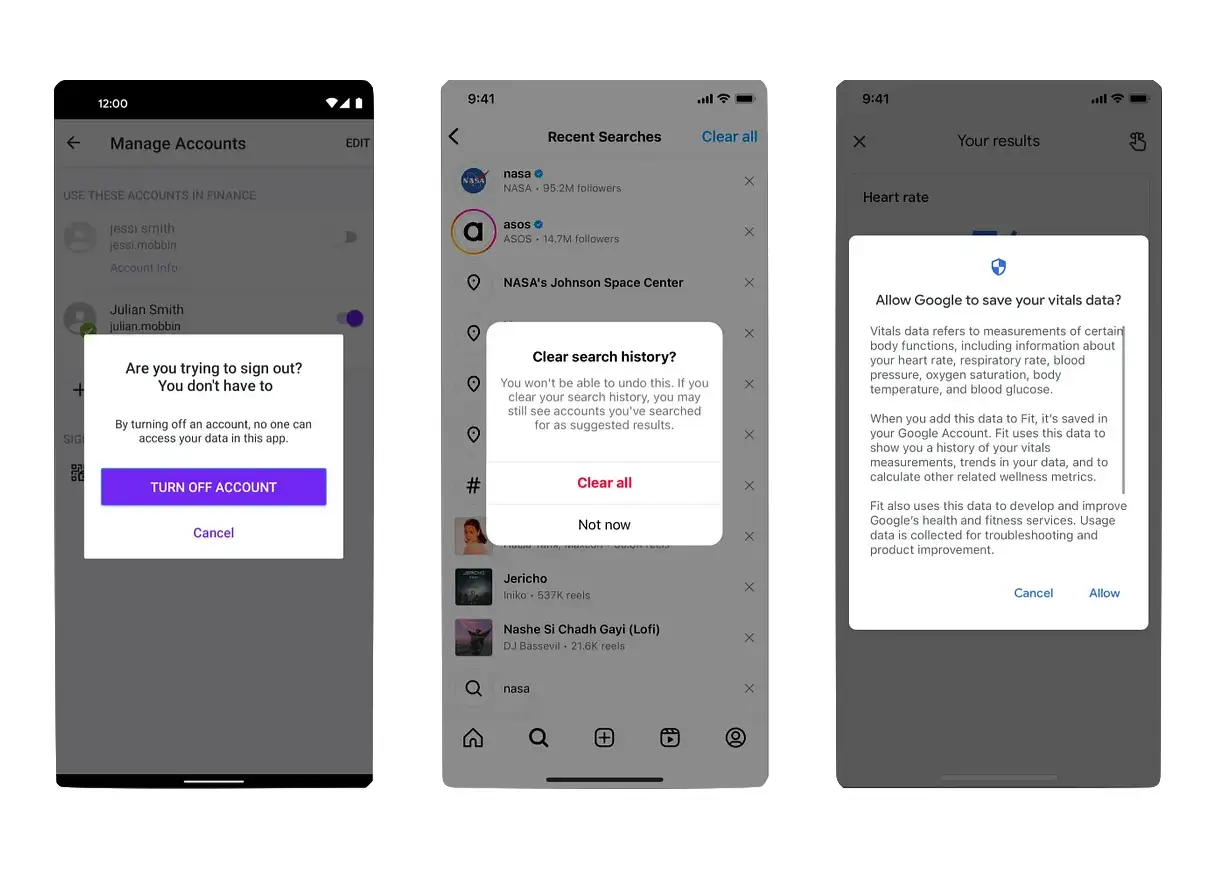

Now let’s talk about interface design. Interface design encourages you to use appropriate interface elements and design guidelines to enable users to interact with the system functionality. Choice of interface elements are search bar, button, text fields, radio buttons, and so on.

When you build your product, keep different platforms in your mind and design accordingly. For example, where on the Web you use “Modal Windows,” on Android you use “Dialogs,” and on iOS “Action Sheets”. Other than that, sometimes organizations also make their own custom components in order to keep the same experience at every platform.

The next is navigation design where you decide how people move from one screen to another on your product. And there are different kinds of navigation systems such as primary navigation, secondary navigation, contextual navigation, site map, and index. Organizations also use breadcrumbs to help people find their way inside their products.

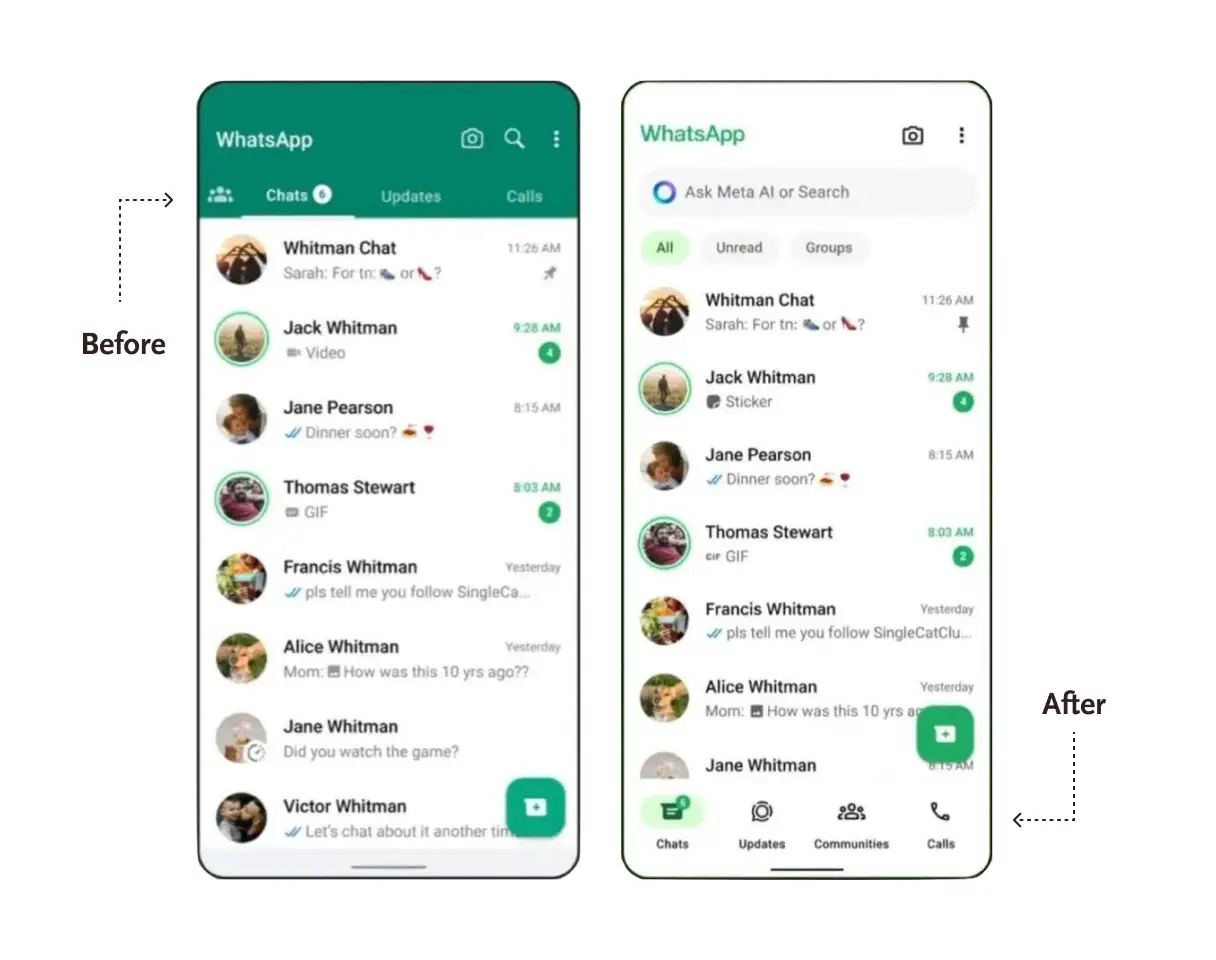

Header, Sidebar, and Footer are good places for web navigation. Tab Bar, Navigation Drawer, and Tabs are common for mobile. For example, a while back WhatsApp used “Tabs” to navigate to its different sections but now it uses “Navigation Bar” to do the same.

Once you finalize your information, interface, and navigation design, you reach the final plane of The Elements of User Experience: the Surface.

Surface

Surface is the only plane where you take care of only one thing and that is: visual design. It’s the realm of user interface designers, whose mission is to build eye-catching and beautiful products that people enjoy. And to do that they primarily rely on

- Color Theory

- Typography, and

- Iconography

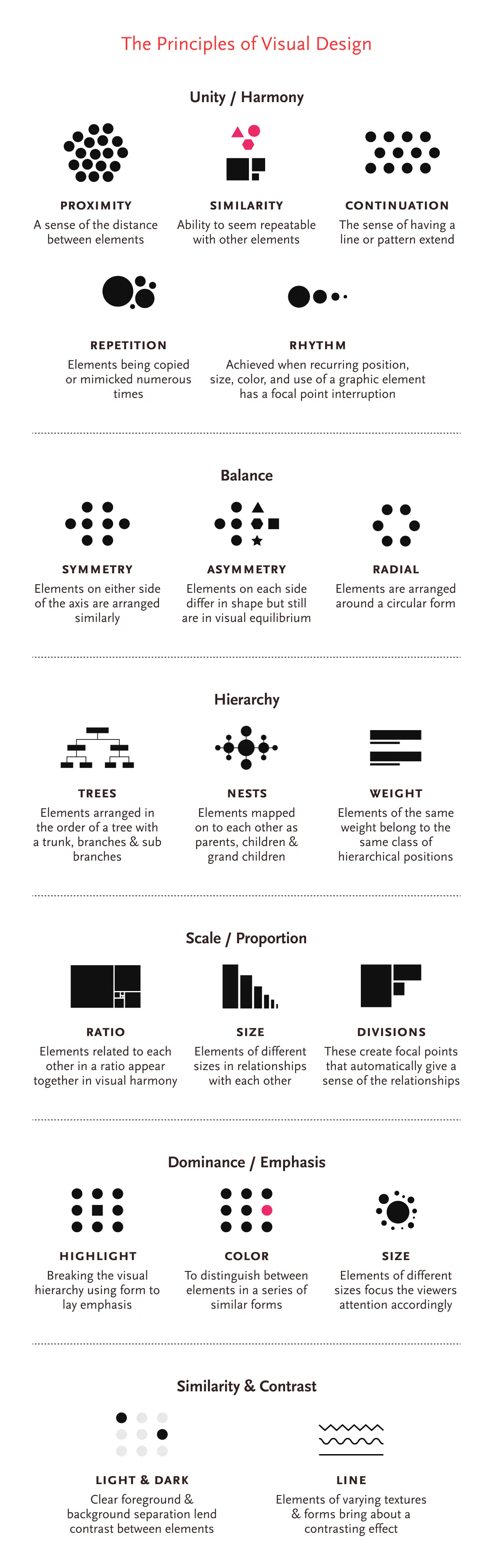

But aside from that, there are hundreds of other subtle elements that often go unnoticed but can make or break a design. Elements such as contrast, repetition, alignment, balance, consistency, proximity, hierarchy, movement, proportion, etc., play a big role in making your product easy to understand and pleasing to use.

And although a lot of higher-ups don’t take visual design seriously, this is the place where users’ emotions take the driver’s seat and make decisions. It doesn’t matter what great things lay beneath the surface, people can only see what is in front of them. So, even though visual design comes at the very last stage in building a product, it is the very first thing people notice.

Today, organizations want to provide a consistent experience to their users throughout all their channels. And for this reason, companies spend millions of dollars each year on their branding. For example, look at how WhatsApp follows a consistent design approach throughout all the different channels such as web, iOS, Android, Mac, PC, etc.

That’s it. These are The Five Elements of User Experience.

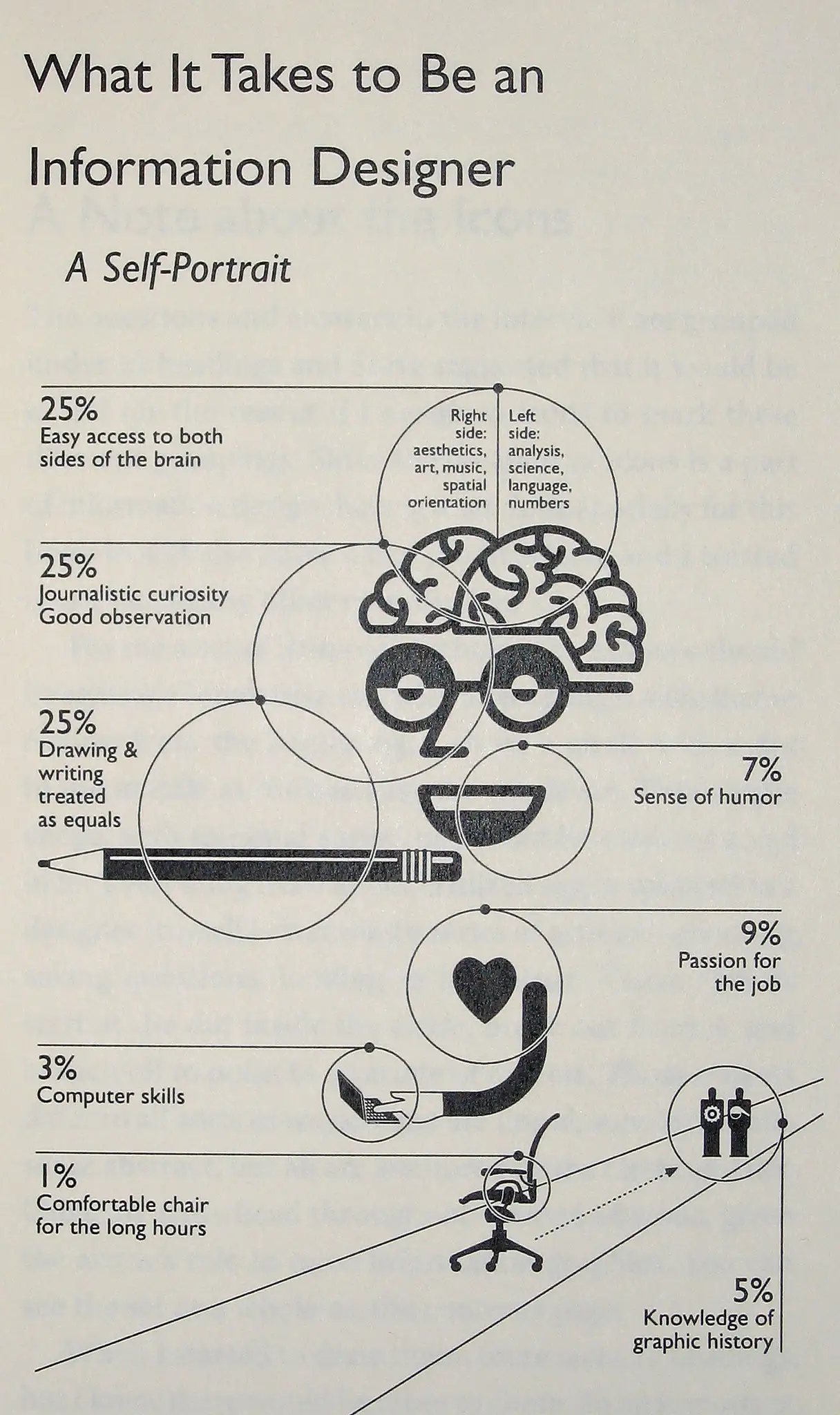

As UX designers spend more time in the trade, they often master several UX disciplines such as business, research, psychology, information architecture, visual design, etc. But what they lack is how to combine these components in a meaningful way to build a product or service.

Here, The Elements of UX provide UX designers a framework, an underlying structure, a recipe that they can use to select the essential ingredients and cook a usable product.

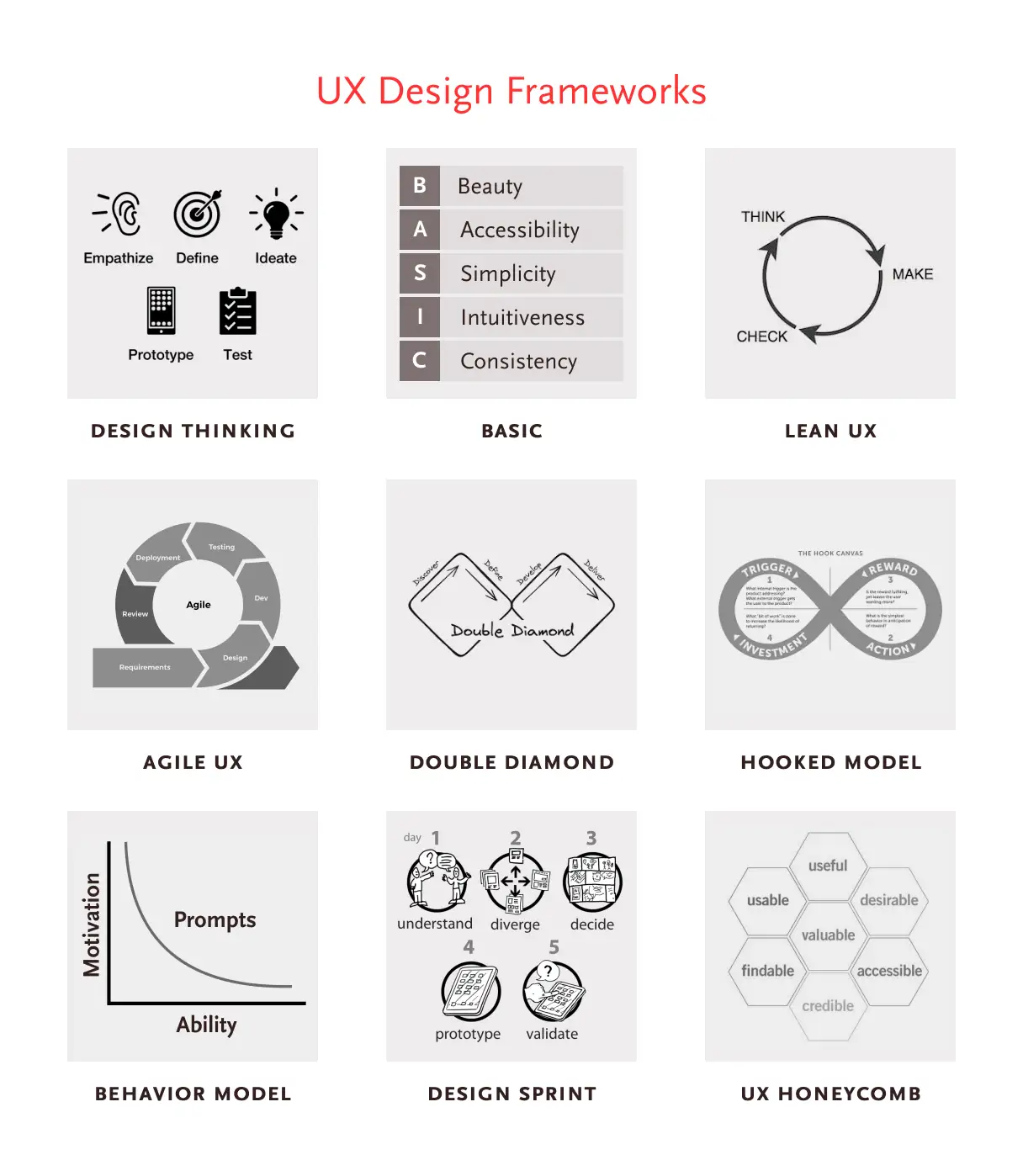

Aside from this framework, there are other problem-solving approaches such as Design Thinking, Human-Centered Design, Design Sprint, Lean UX, Agile UX, the Double Diamond model, etc., that also help you create usable products. You’ll explore them as you move forward. Stay tuned.