Focus on the user and all else will follow.

—First principle among Google’s Ten Things We Know to Be True

Not only UX designers but also organizations love processes. And why not? A good process ensures or at least increases the chances that work will be completed within the given timeframe and budget.

Similarly, a design process can help reduce the unpredictability of design work that companies often complain about. And even if your creative juices aren’t flowing on a particular day, a design process might give you the flexibility to focus on something less demanding in the meantime.

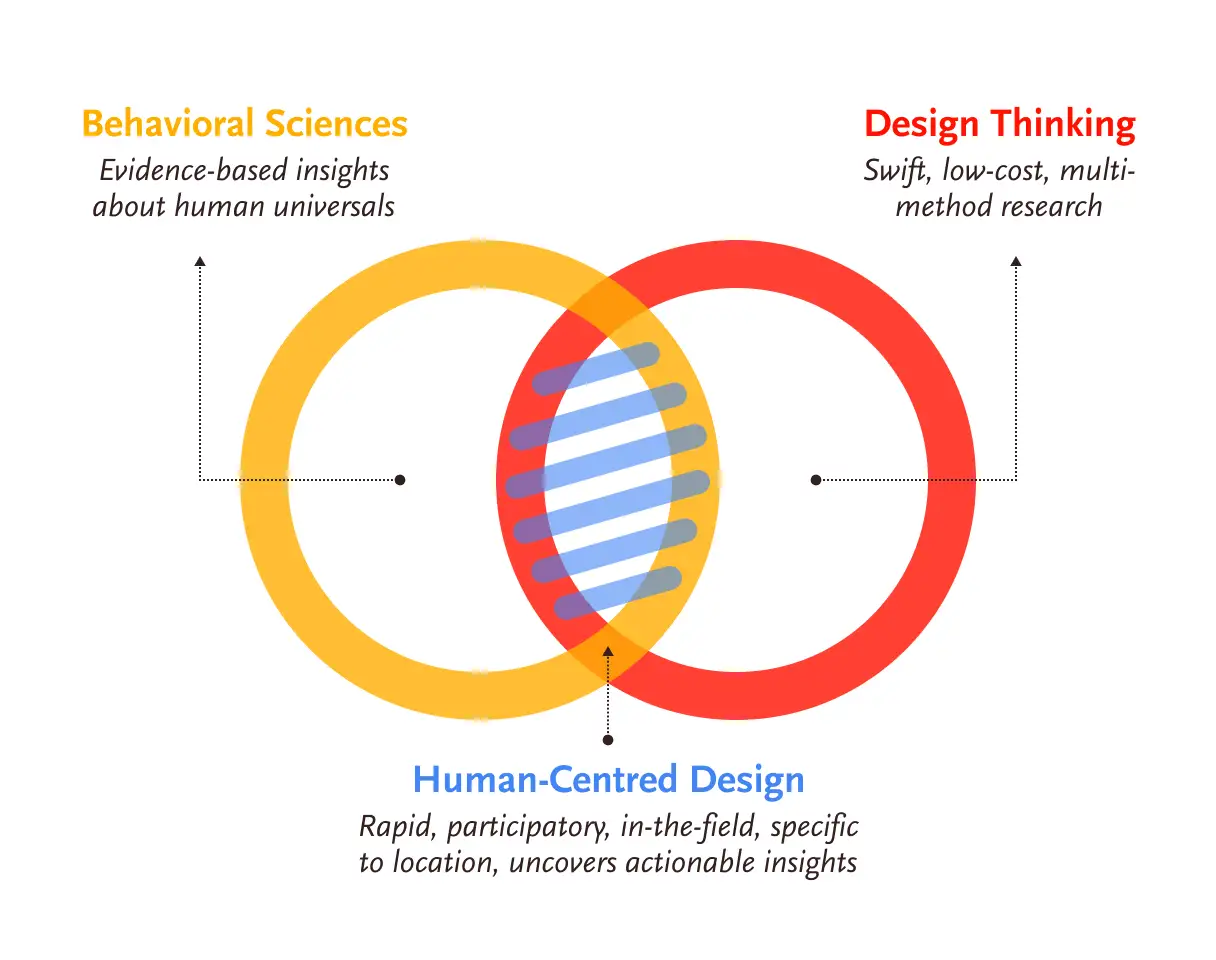

But before you dive into any specific design process, let’s talk about Human-Centered Design (HCD) first.

A Manifesto for Design

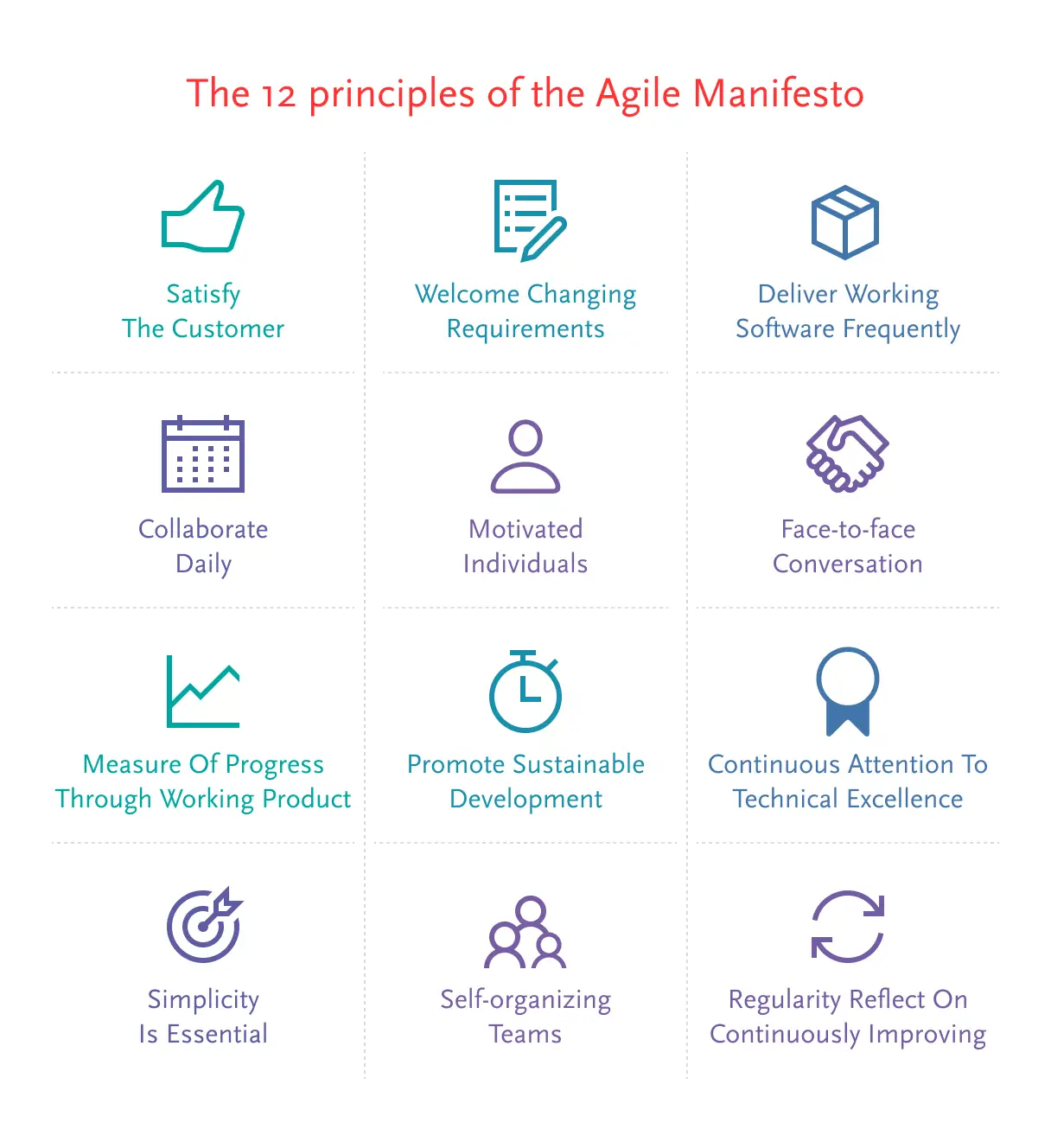

Human-Centered Design is part process and part philosophy, but it doesn’t require you to follow a rigid set of rules. In this way, it’s similar to Agile, which outlines a set of 12 principles while giving you the flexibility to make your own rules. And that’s exactly what organizations do. They craft their own customized flavor of Agile that suits their unique needs.

Similarly, Human-Centered Design also offers a few guiding principles that you can keep in mind while shaping your own version of a design process.

Historical Context

I’m not sure who coined the term “Human-Centered Design,” but Norman definitely popularized it. Back in the ’80s, when he began working in design, the field was not what it is today. Computers were still in their nascent stage, and even the people who designed them often struggled to use them.

He recalls an anecdote about how the UNIX operating system used a text editor called ed. People would work on that editor, go home, and return the next day only to find that all their work had vanished. Why? Because they had forgotten to save their work before closing the editor. And the editor didn’t even bother to show a warning message. Alas, engineers expected people to behave in a specific way, leaving no room for human error.

So Norman began studying people who used these complex systems to better understand their behavior. And he didn’t limit himself to computers alone but explored any domain where people’s lives were at stake. He worked on aviation safety at NASA and was also part of the team that investigated the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident. He referred to the people who used these systems as users.

User Centered System Design = University of California, San Diego

At that time, Norman was at the University of California, San Diego. There, along with his research group and Stephen Draper, he edited a book titled User Centered System Design. The title, in part, was inspired by his university’s initials, UCSD.

In the book, they emphasized two core ideas:

- Focus on the users

- Everything is a system

However, over time, they grew uncomfortable with the word user. They realized they were designing for people, so it made more sense to call it people-centered or human-centered design. Eventually, they replaced the word user with human. And the word system gradually faded away. That is how the term “Human-Centered Design” came into being.

Zero Degrees of Empathy

On a slightly different note, referring to people as users can be a form of dehumanization. This idea is explored by Simon Baron-Cohen in his book Zero Degrees of Empathy. Historically and even today, when people want to harm others, they begin by dehumanizing them. It makes it easier to justify their actions.

Ironically, Simon is the cousin of comedian Sacha Baron Cohen. Known for characters like Ali G, Borat, Brüno, and Admiral General Aladeen, Sacha’s satirical work is considered dehumanizing by some. In fact, popular cinema is filled with examples of dehumanization.

Django Unchained

In the movie Django Unchained, the character Calvin Candie claims that, according to the so-called science of phrenology, everyone has 3 dimples in the back of their skull. In Africans, they exist in the area associated with submissiveness while in Whites, they appear in the area linked to creativity.

Essentially, he argues that Africans were genetically destined to be slaves. It was his way of justifying slavery by demeaning the African race. But when Dr. Schultz remarks, “Alexandre Dumas was black,” the look on Candie’s face was worth seeing — stunned and defeated by a simple truth.

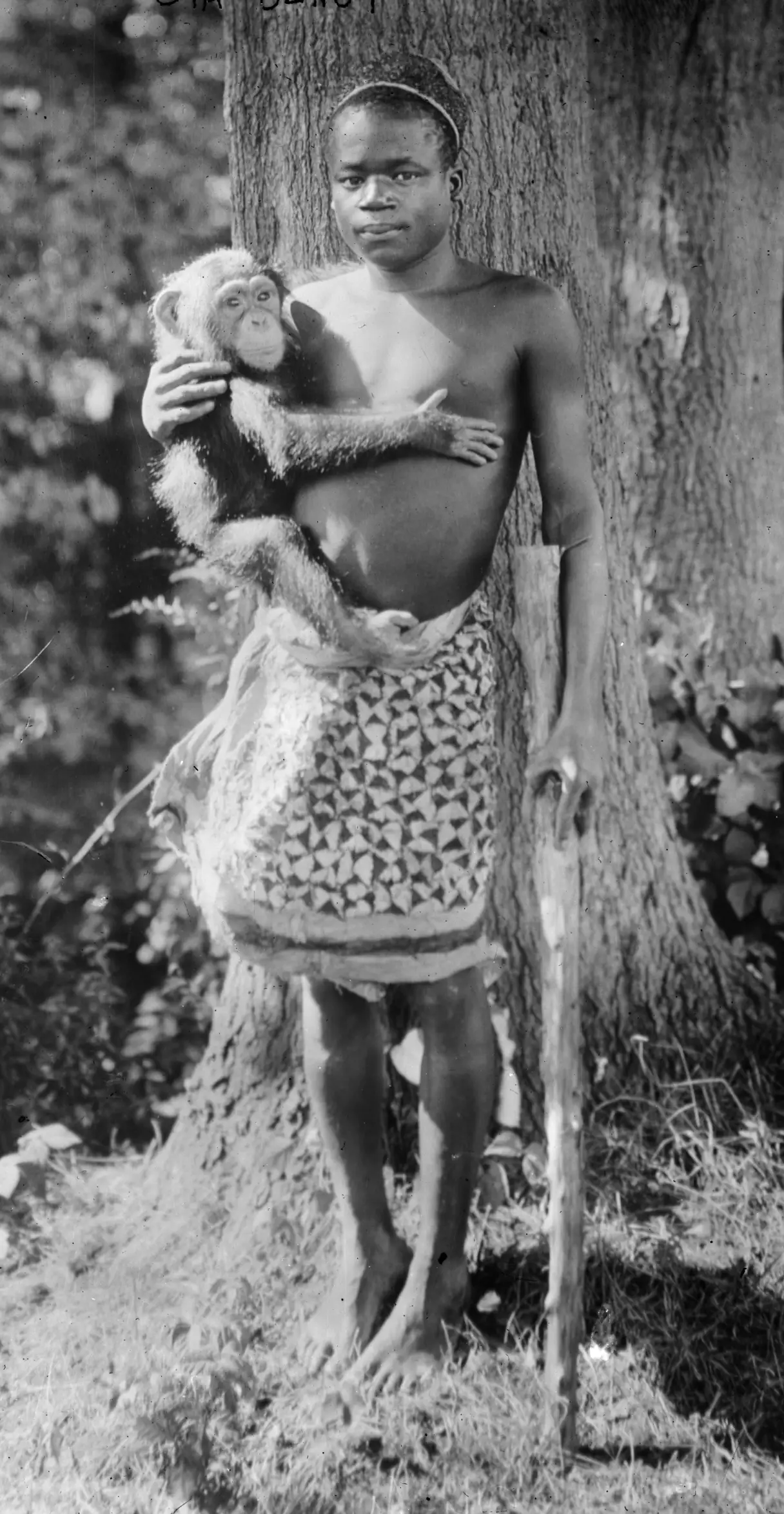

You may have also seen images from history where Westerners put marginalized groups on display in zoos to showcase the supposed inferiority of their culture. And most people didn’t even think they were doing something wrong — because they believed they were superior.

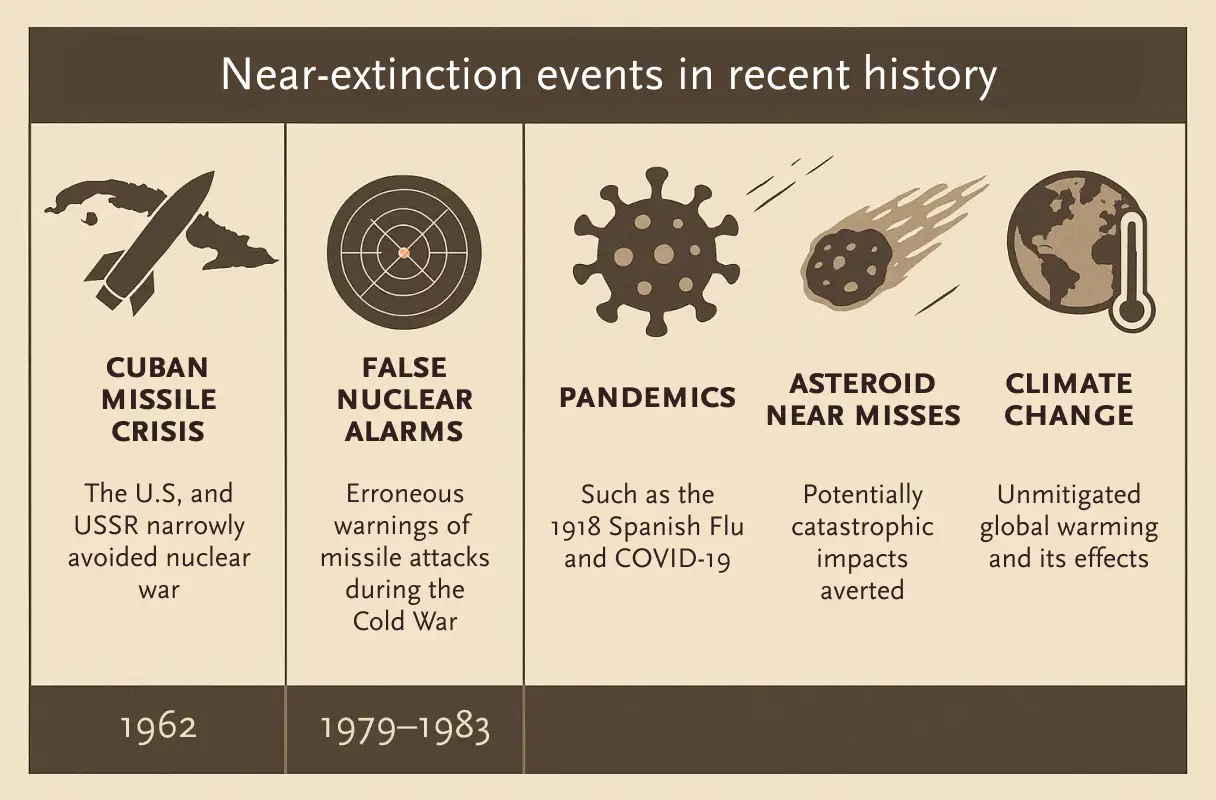

Even today, we see similar acts of dehumanization across the world. In India, some Hindus refer to Muslims as rakshasa while some Muslims label Hindus as kafir. Similarly, in the Israel-Palestine conflict, people on both sides use terms like militants or blood-suckers to vilify one another. No wonder Homo Sapiens eradicated all other human species from the face of the earth. And even in the recent past, we’ve come dangerously close to wiping out all of humanity more than once.

Are you sure you’re sane — and incapable of such evil?

The Stanford Prison Experiment

If you want to see how ordinary people can commit evil acts once they begin to see others as less than human, read about the Stanford Prison Experiment. A controversial study, conducted in 1971 by psychologist Philip Zimbardo, had to be shut down after just six days, due to the rapid escalation of abusive behavior and emotional breakdowns. You can also read Zimbardo’s book The Lucifer Effect to learn more about it.

But cruelty isn’t limited to humans only. Many non-vegetarians justify killing animals with arguments like:

- They don’t feel pain.

- They don’t have emotions.

- Their population would become uncontrollable.

I’m also a non-vegetarian but now I realize how poorly I used to justify my choices. Anyway, let’s get back to Human-Centered Design.

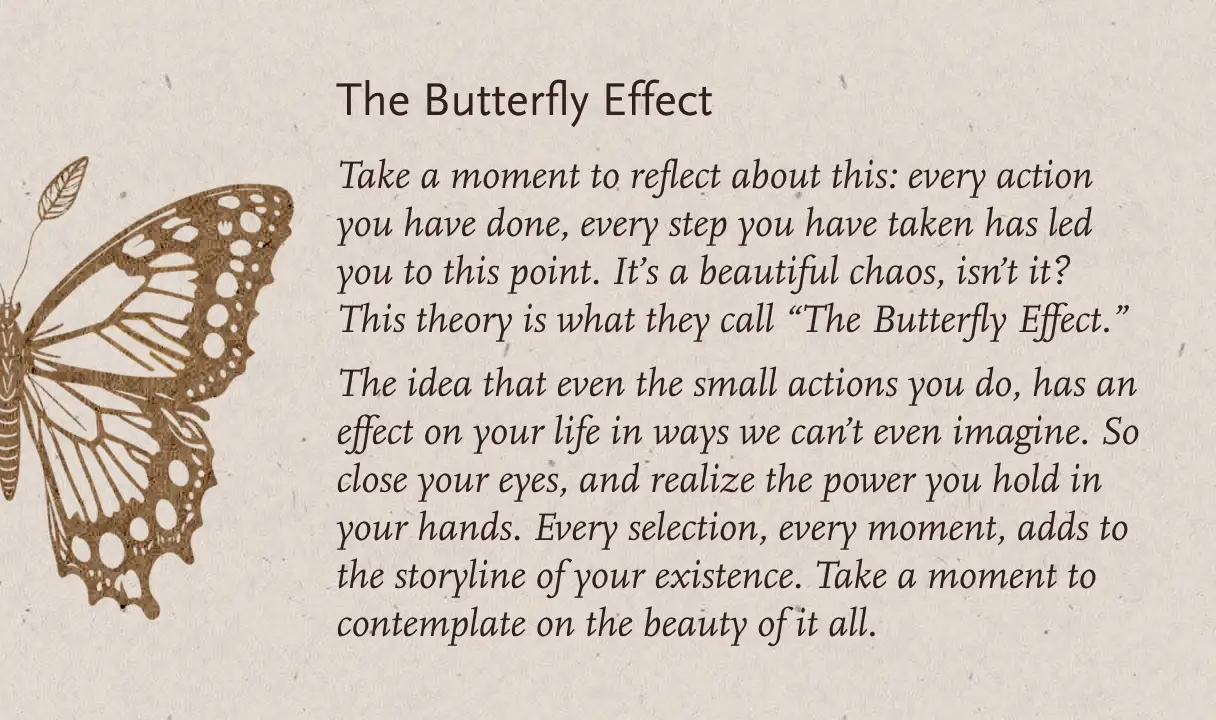

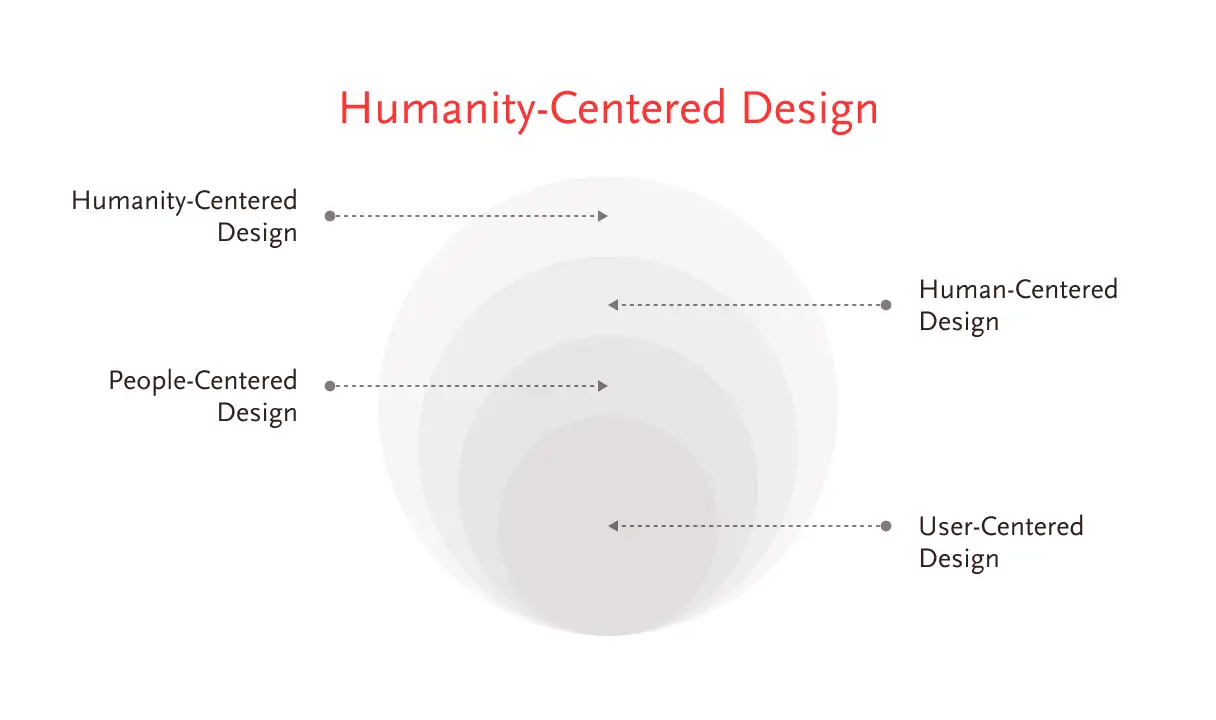

Humanity-Centered Design

Over time, Norman realized since everything is a system, you can’t make a change in one place without affecting others. As the saying goes, a butterfly flapping its wings could cause a tornado on the other side of the world — a concept known as the butterfly effect.

So instead of focusing on people in a specific context, think about the impact on all of humanity. And that’s how Human-Centered Design evolved into Humanity-Centered Design.

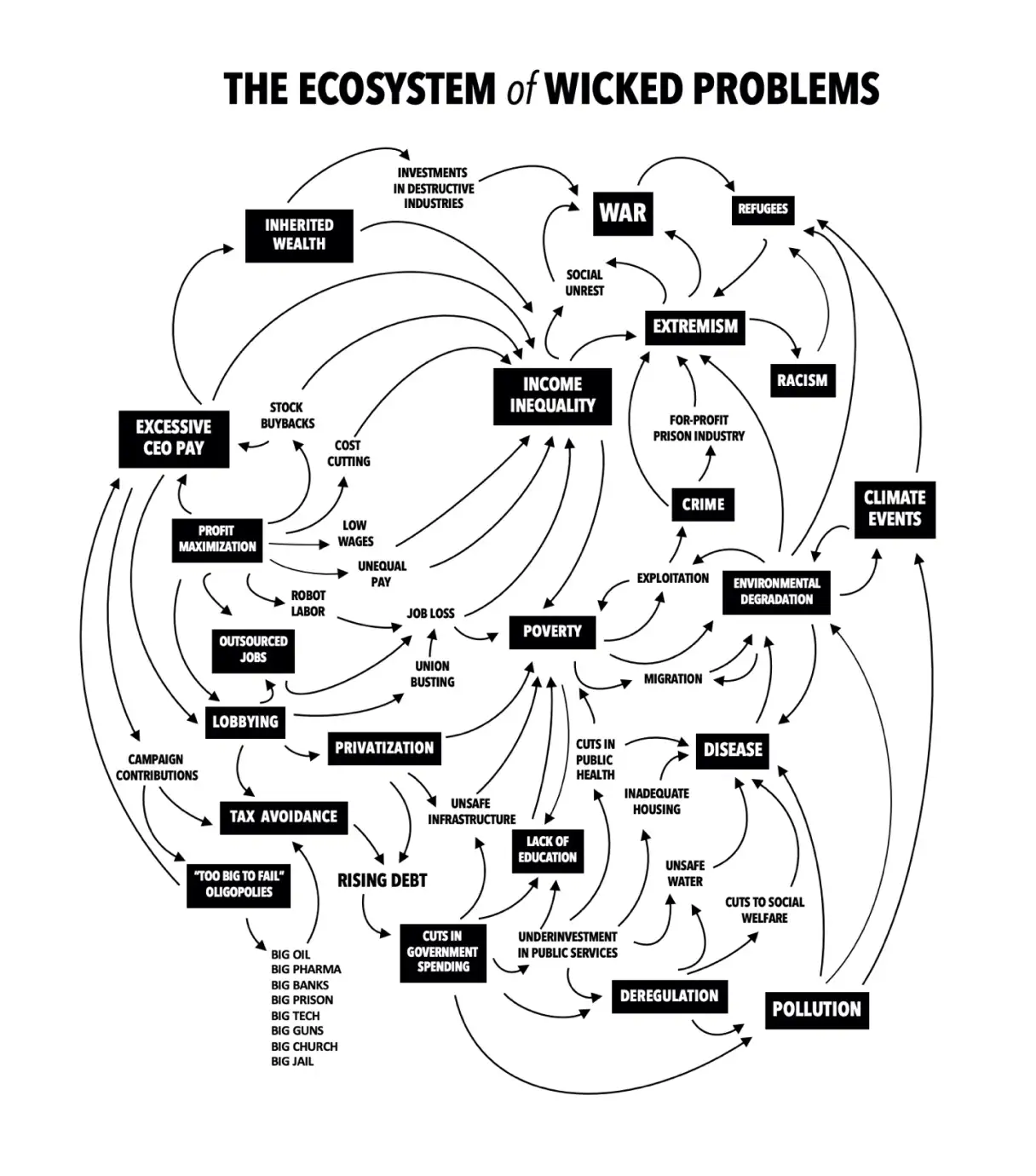

According to it, design should not be limited to creating just a piece of software. It should aim to tackle big, universal problems, often referred to as wicked problems, such as:

- Poverty and inequality

- Ethics in AI

- Public health crises

These are complex and interconnected problems that are difficult or even impossible to solve. And that’s where you should focus, because ultimately, your job is not just to serve users, but to serve all of humanity.

This journey from User-Centered Design (UCD) to Humanity-Centered Design (HCD) reflects not only the evolution of a design process, but also how Norman himself grew as a designer over the years. Who knows what new name we’ll see in the future?

Now, it’s time to explore 3 distinct flavors of Human-Centered Design.

Three Flavors of Human-Centered Design

Over time, different schools of thought have developed their own versions of Human-Centered Design. While they share core ideas, each brings its unique perspective to the table. Here they are:

- Norman’s Human-Centered Design

- IDEO’s Human-Centred Design

- ISO’s Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems

Let’s take a brief look at each one, one at a time.

Norman’s Human-Centered Design

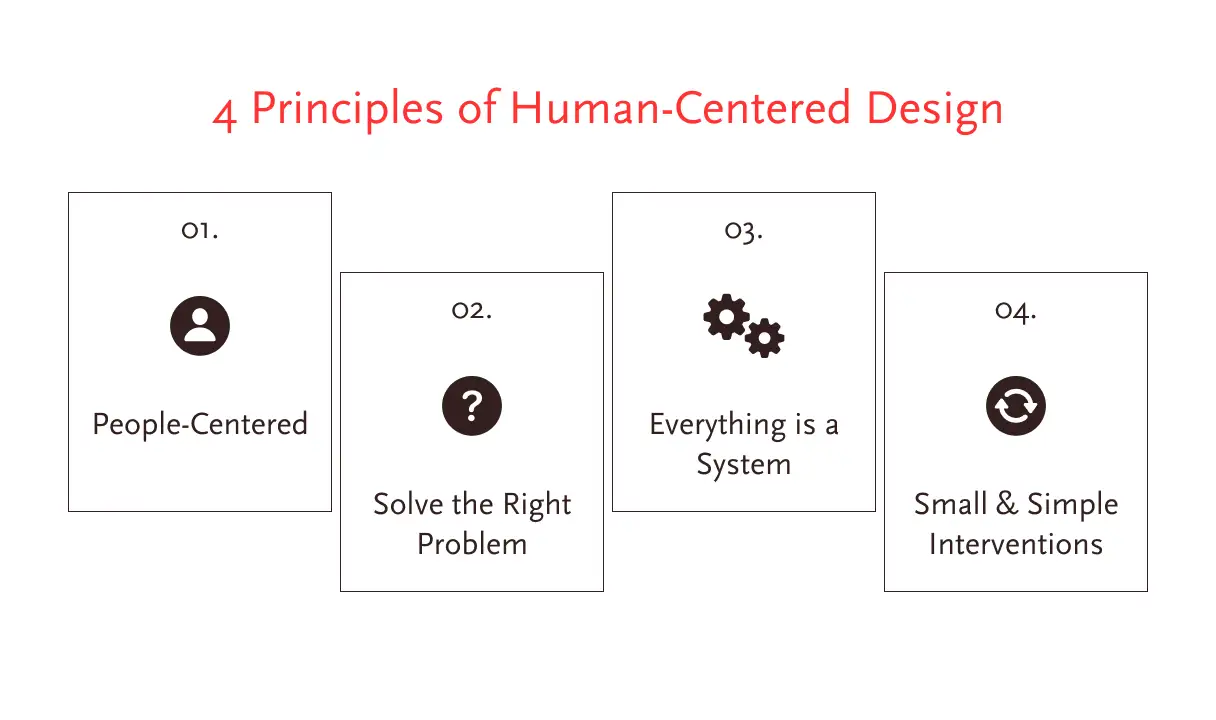

Don Norman’s HCD has four core principles:

1. people-centered

Focus on people. If you don’t, then you won’t be able to understand what is the real problem to solve. Go out, talk to them, empathize with their pain points, put yourself into their shoes and walk a mile to feel what they feel.

Don’t assume you don’t need to know what people want because you’ve read those famous Henry Ford or Steve Jobs quotes dismissing market research. First, you’re neither Ford nor Jobs. Second, you don’t actually know how much research they did behind the scenes.

2. solve the right problems

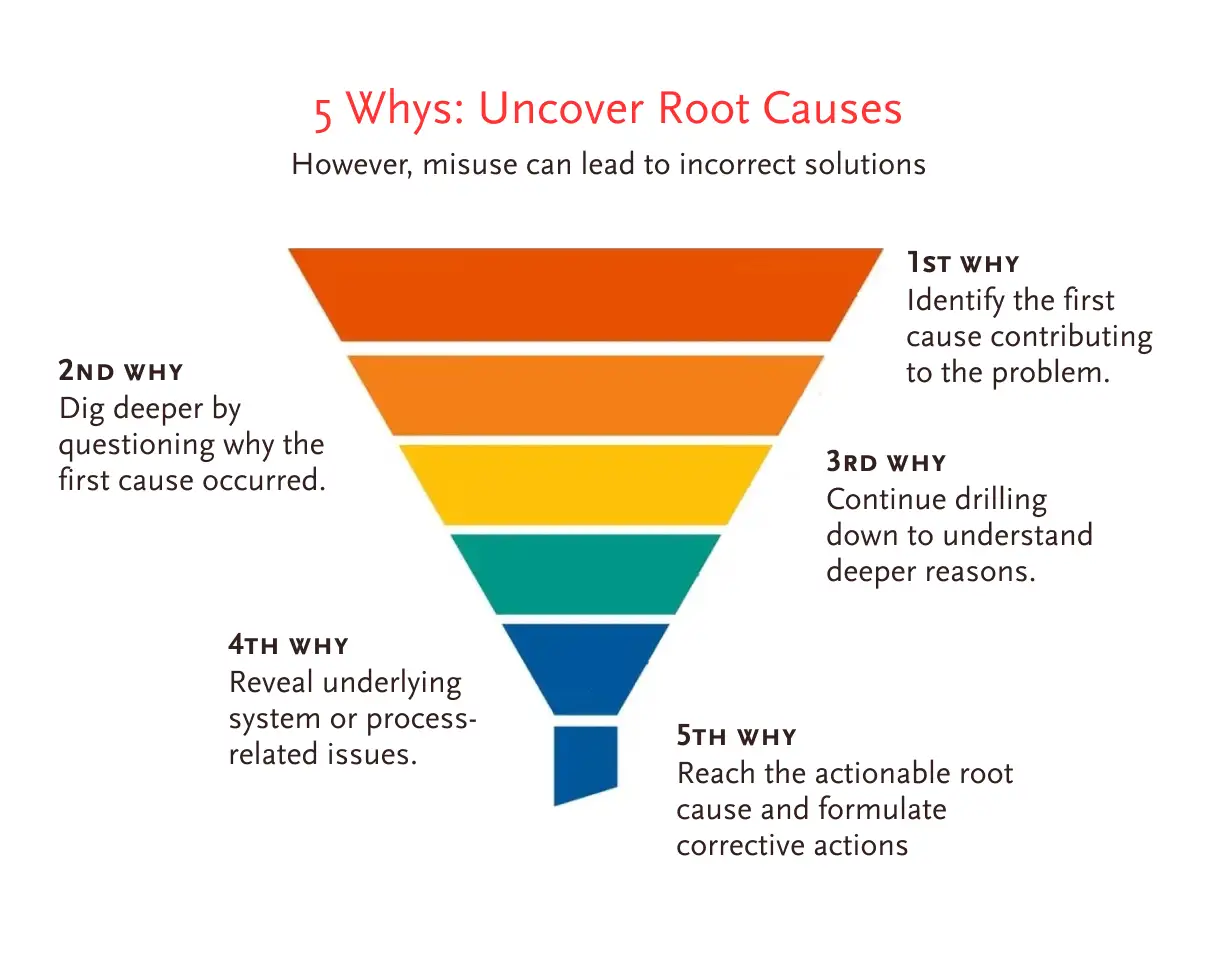

One of Norman’s golden rules is: Never solve the problem you’re asked to solve. Why? Because in most cases, the problem you are asked to solve isn’t the real problem. It’s just a symptom. And fixing the symptom might temporarily solve the issue, but in the long run, it will resurface again.

A powerful method to uncover the root cause is the “Five whys.” Developed by Taiichi Ohno at Toyota, it helps to identify the origin of a problem by asking why 5 times. Each why builds on the previous answer, and by the time you reach the 5th, the root of the problem reveals itself.

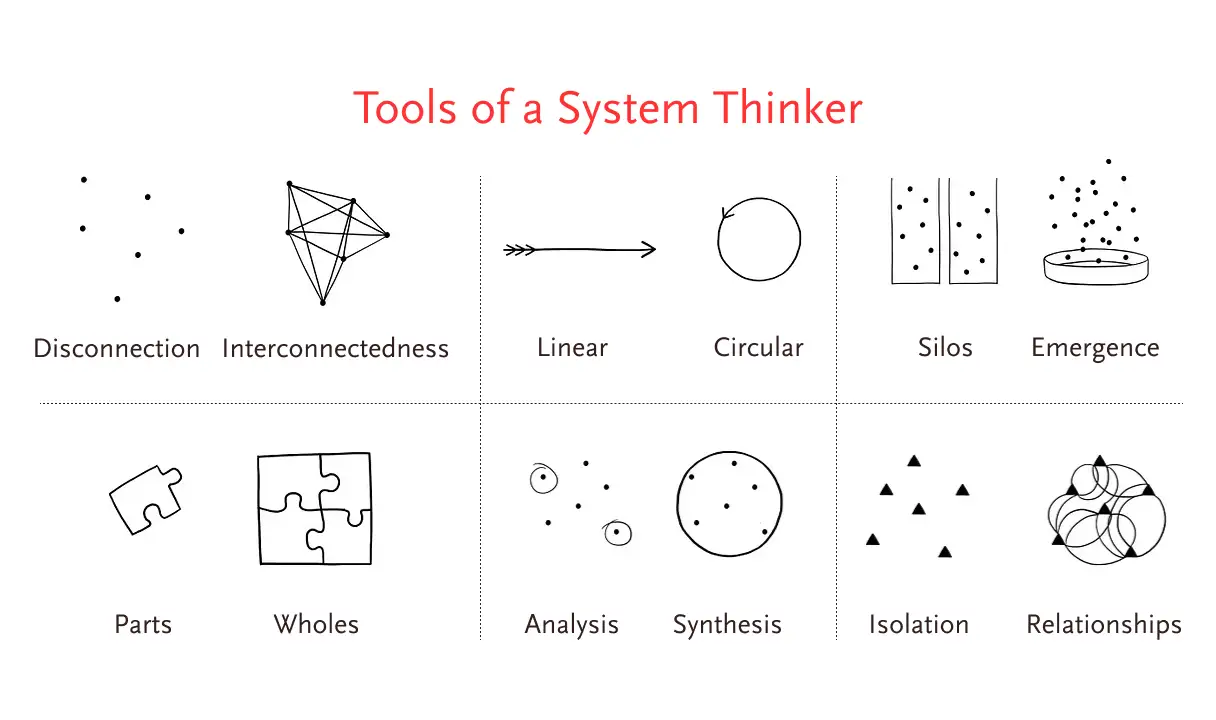

3. everything is a system

Take care of each individual component of the system but don’t forget that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There is no such thing as a stand-alone feature or decision. Everything is connected. Even your life is a system too. And every change you make in one area of it affects the others.

Let’s say you workout for an hour every day. But one day, you decide to stop exercising for 6 months to focus on learning design. Fast forward 6 months — you’ve become a designer but you’ve also sacrificed your health. Now, it becomes hard to motivate yourself to start working out again. The 6‑month break turns into a year… then two… and eventually, you start losing muscle, feeling tired all the time, and gain weight. All of this from one small decision. That’s how systems work: nothing happens in isolation.

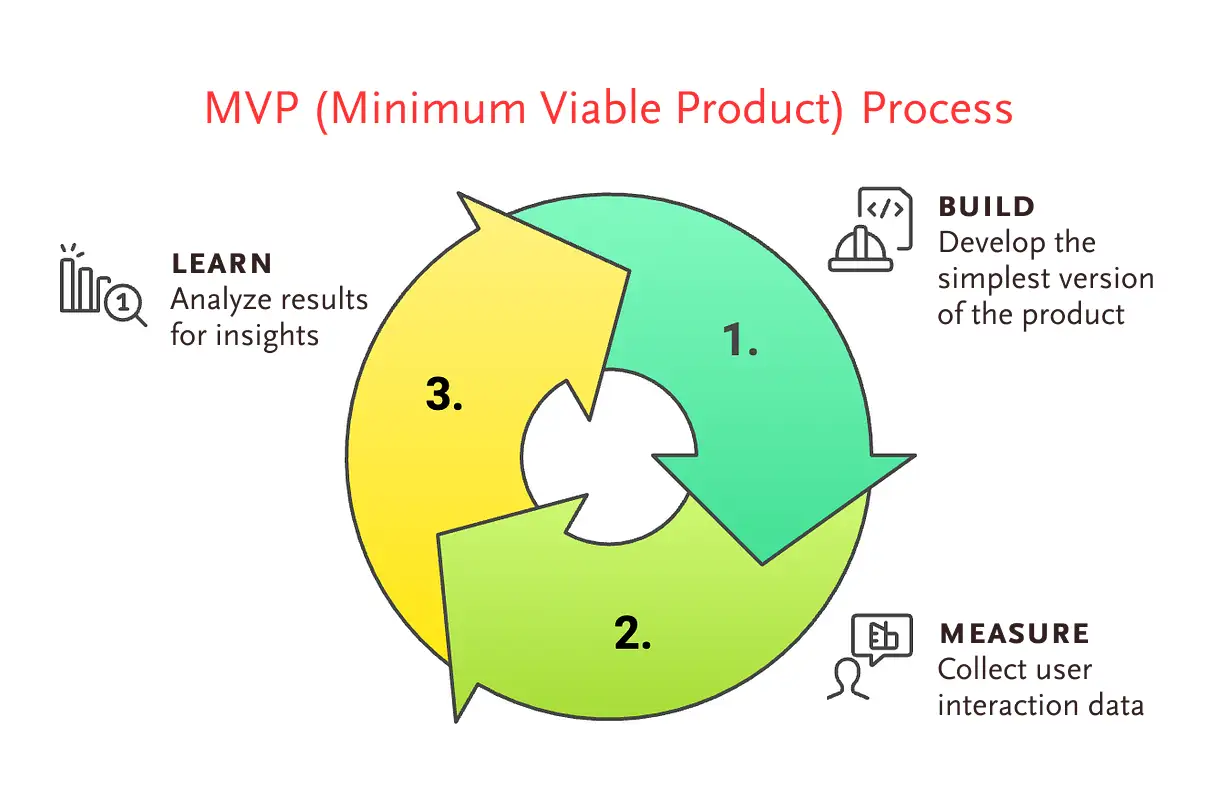

4. small and simple interventions

Do iterative work. Even if you are people-focused and solving the right problem, don’t try to change the entire system all at once. You’re designing for people and people are complex and there are 8 billion of them. That’s a hell lot of interconnected moving parts to manage.

On top of that, individuals behave differently when alone than they do in groups. Then, those groups are part of larger societies, which are even more complex. So psychology, group behavior, sociology, etc. all of these factors come into play. One wrong move, and you might not get a second chance to correct it. That’s why it’s smarter to make small changes, gather feedback, measure results, and, if everything looks great, implement them.

IDEO’s Human-Centred Design

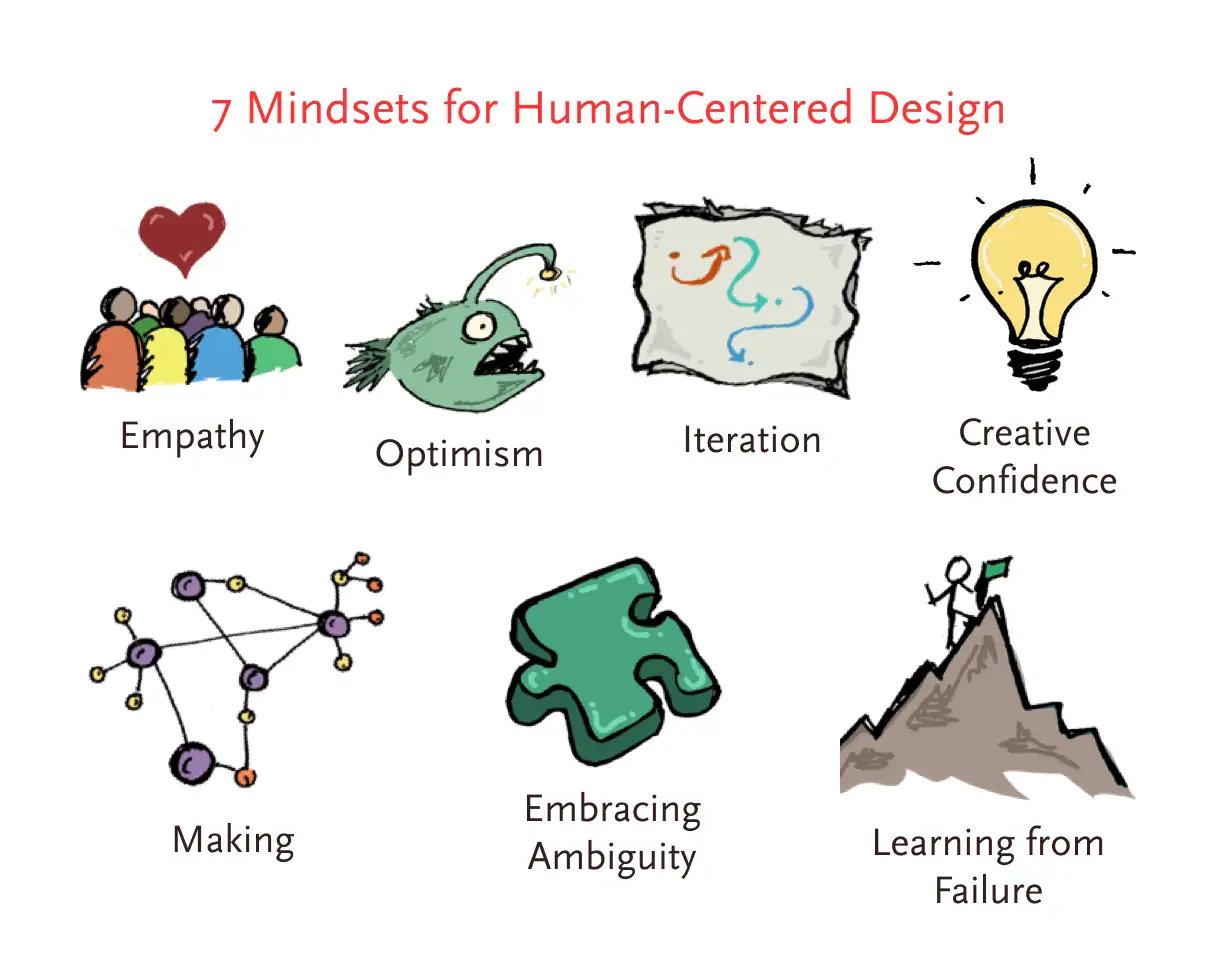

IDEO brings its own flavor of Human-Centered Design that begins with a mindset. According to them, before using HCD, you should first embrace 7 mindsets: Empathy, Optimism, Iteration, Creative Confidence, Making, Embracing Ambiguity, and Learning from Failure

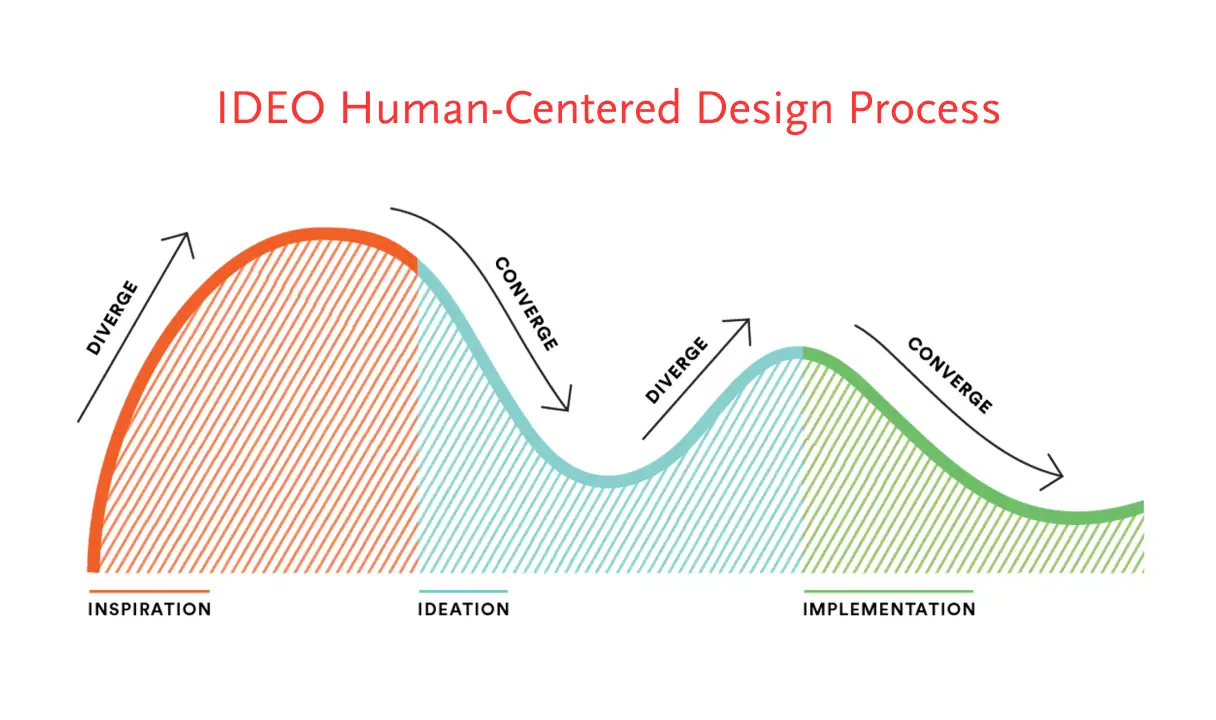

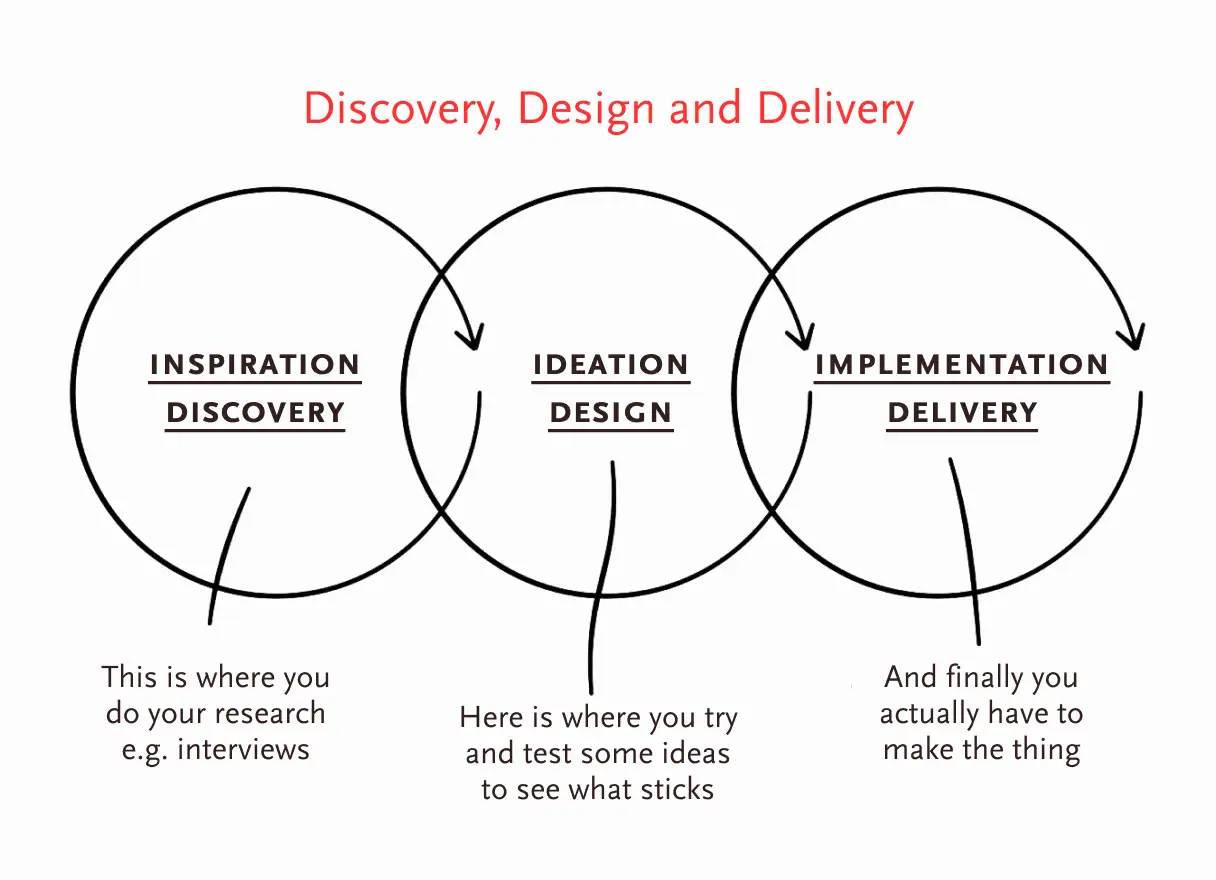

Once you cultivate this mindset, you can use their process to create your solution. So, whatever design challenge you take—no matter how big or small it is—goes through their three phases.

1. inspiration

Here you go out and observe people, talk to them, empathize with their pain points, listen to what motivates them, see their typical behaviors, desires, hopes, opinions, etc. In short, you submerge yourself so deeply into their world that you almost become one of them. And only then you can feel what they feel and build a solution that truly represents their need.

2. ideation

Designers are always in a hurry to build a solution. But your first idea is rarely the best one, so you generate a ton of ideas first. Still, an idea can only work if it comes from the very people who are facing the problem. After all, who could be a better judge than them to evaluate how good the idea is?

That’s why you include these people in the ideation process. You build a prototype, show it to them, take their feedback, and refine it further. Once you have a clear winner, you move to the third phase.

3. implementation

Here you take your idea into the real world. And that is where it has to prove its worth. Here, it has to show whether it is worth its salt. In the ideation phase, there are a lot of things that you can not test due either to limited time or to the number of participants. But in the real world you have enough time, plenty of users, and unpredictable variables to test your idea.

If you want to learn more about IDEO’s process, head over to Design Kit and download their free resources including:

- The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design

- Design Kit: The Facilitator’s Guide

You’ll also find 57 design methods that you can apply across all 3 phases of their process — along with real-life case studies among other things.

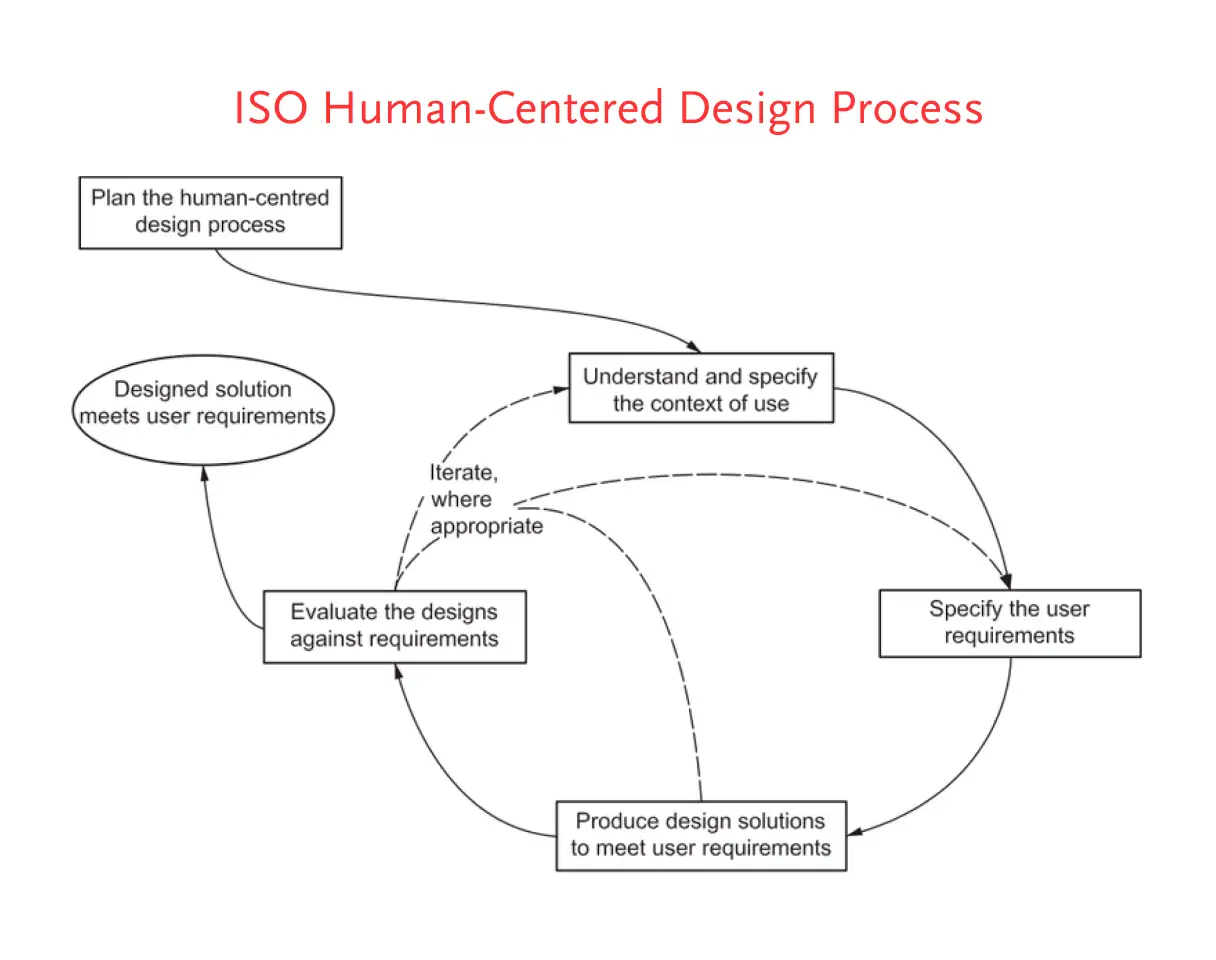

ISO’s Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems

This ISO flavored Human-Centred Design is formalized as an international standard — ISO 9241–210. It’s also guided by a few principles like:

- The design is based upon an explicit understanding of users, tasks and environments

- Users are involved throughout design and development

- The design is driven and refined by user-centred evaluation

- The process is iterative

- The design addresses the whole user experience

- The design team includes multidisciplinary skills and perspectives

The following are their core activities you should perform while developing a system, product, or service. They are more or less similar to other Human-Centered Design processes:

- Understanding and specifying the context of use

- Specifying the user requirements

- Producing design solutions

- Evaluating the design

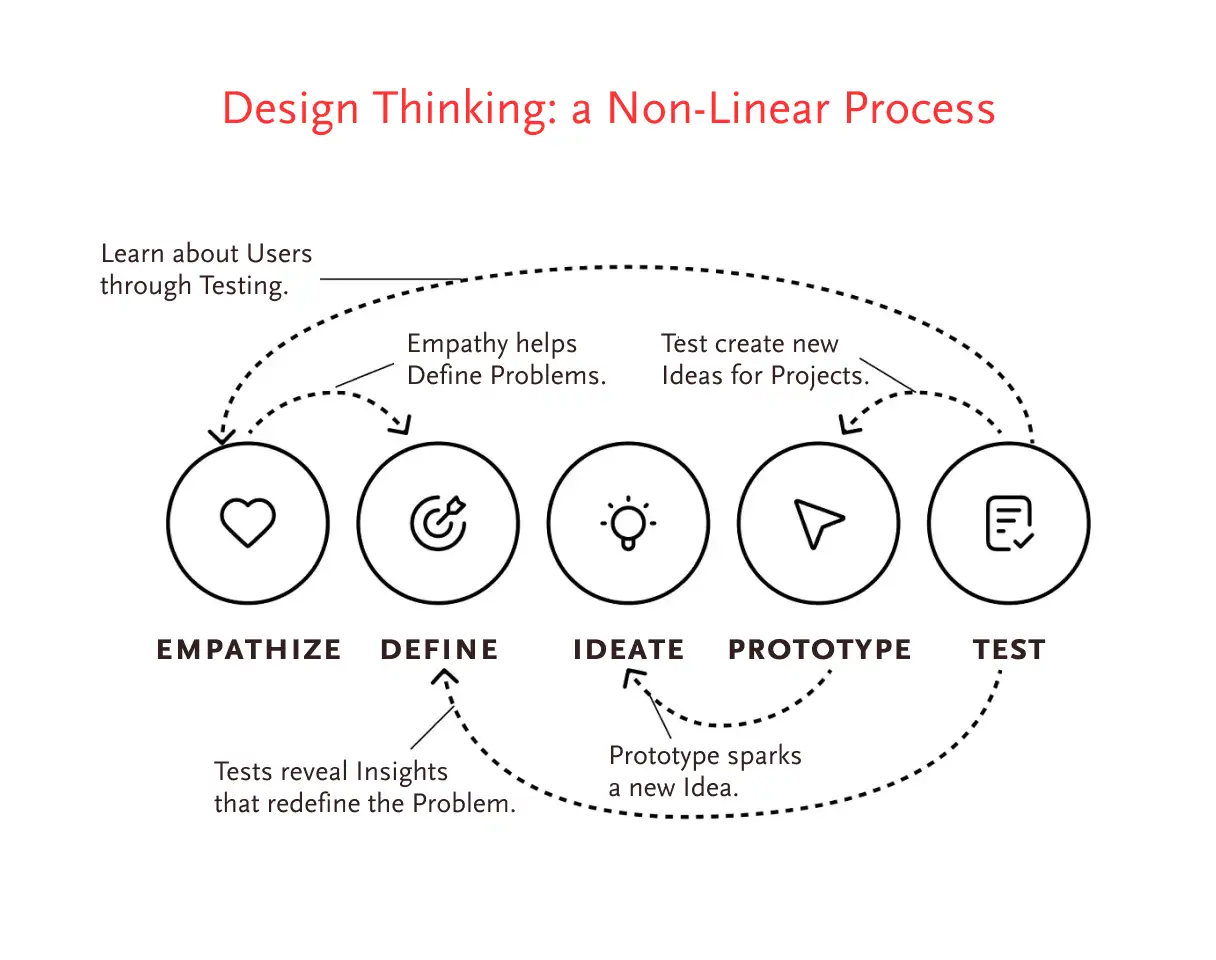

Okay, these are my two cents on Human-Centered Design. But here’s the thing, while all these principles, mindsets, and processes are essential to build a Human-Centered Design, how do you actually build one?

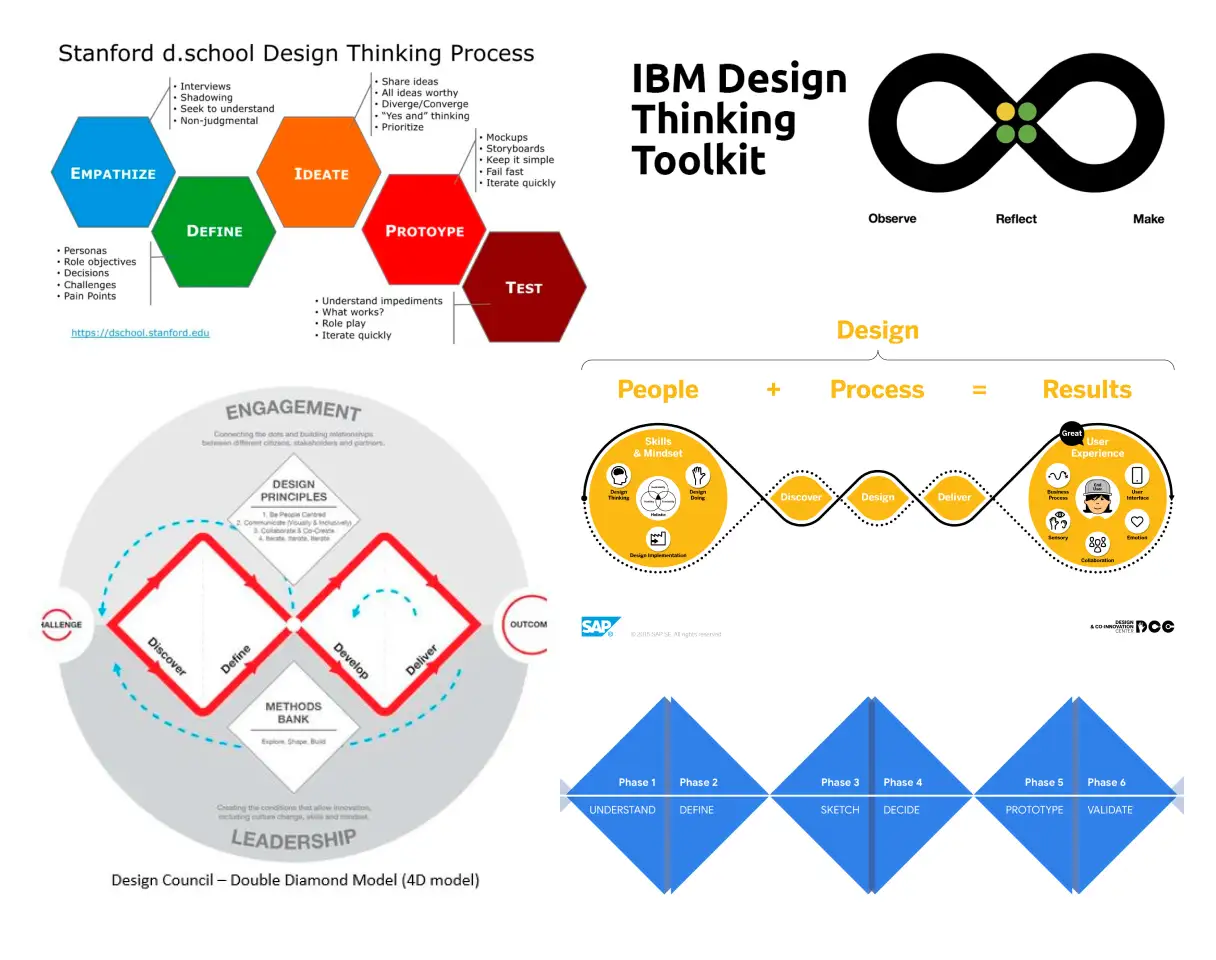

HCD is mostly theoretical, you need something concrete. You need a step-by-step framework that guides you through the murky waters of design and suggests enough tools and techniques so that you can generate novel, robust and doable solutions.

Enter Design Thinking — a problem-solving approach. While Human-Centered Design focuses on the why, Design Thinking focuses on the how. And that’s what makes the Design Thinking process far more popular than Human-Centered Design. So stay tuned to learn what Design Thinking is and how you can use it in your work.