Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. —Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

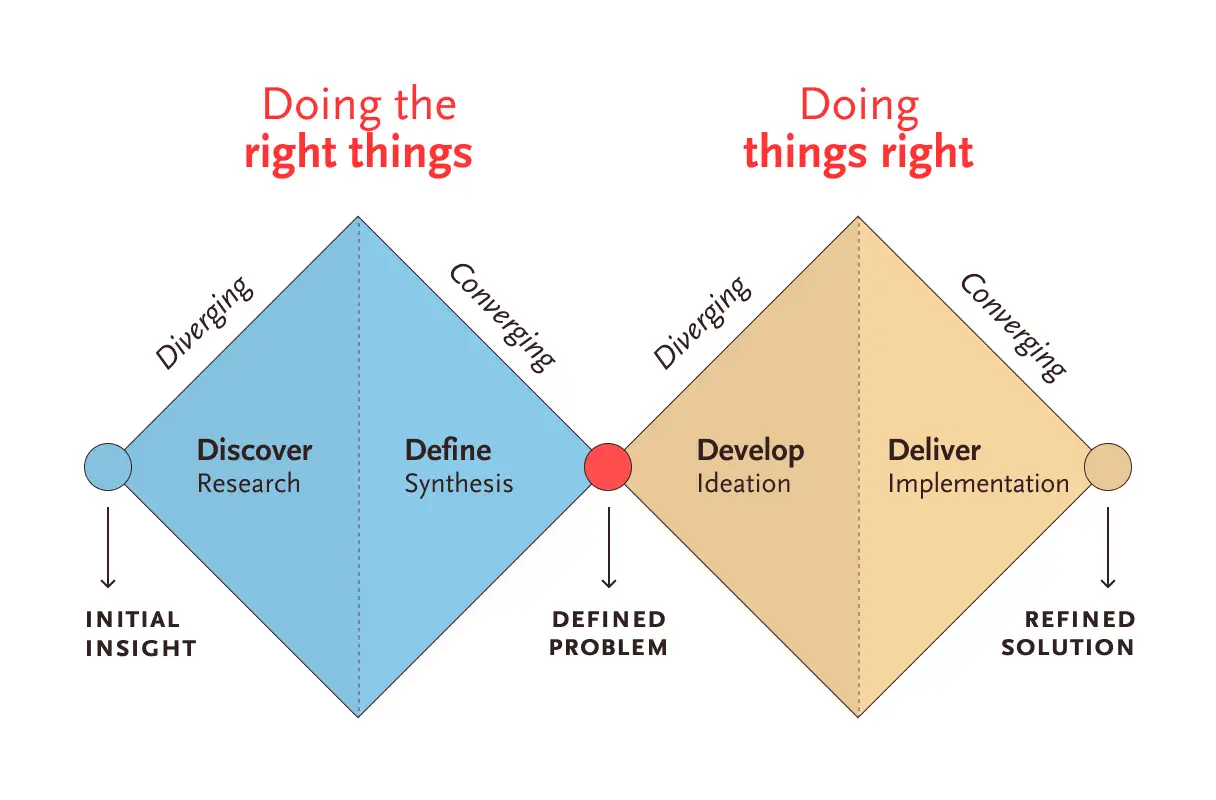

This quote sums up what I’m going to explain in this article. Earlier, I wrote about a couple of problem-solving frameworks. They all follow a few steps, and each step has its own tools and techniques that enable us to:

- First: do the right things.

- Then: do things right.

Now, to this long list of tools and techniques, add one more: task analysis. It’s one of the most effective methods to help you in the problem-solving process. Let’s see how, but first, some context.

Human Beings Are Creatures of Habit

Except for a chosen few, we repeat similar activities throughout our lives. We share similar desires, face similar problems, and use similar products.

And every product we use answers two questions:

- What are our needs, desires, or pain points?

- How does it solve them?

A few of our core needs, like food, clothes, and shelter are easy to guess. And even among them, our love for sugar, fat, sex, intoxication, and cheap entertainment is well-known and heavily exploited by big industries.

Beyond these, we have thousands of other needs that must be fulfilled. But discovering them isn’t easy, because we don’t even know what we truly want. We live in our own small worlds, repeating the same things day after day, until we stop noticing what’s wrong with them. We become slaves to our habits and don’t even realize we might need help.

That’s why we need someone with a fresh pair of eyes—someone who can step outside our world, observe our monotonous lives, watch how we perform our daily chores, and notice:

- what our deep desires are,

- what bothers us, and

- what makes us happy.

And build a product that fulfills those desires, eases our pain, and brings our lives closer to how they should be. In short, we need UX people 🙂.

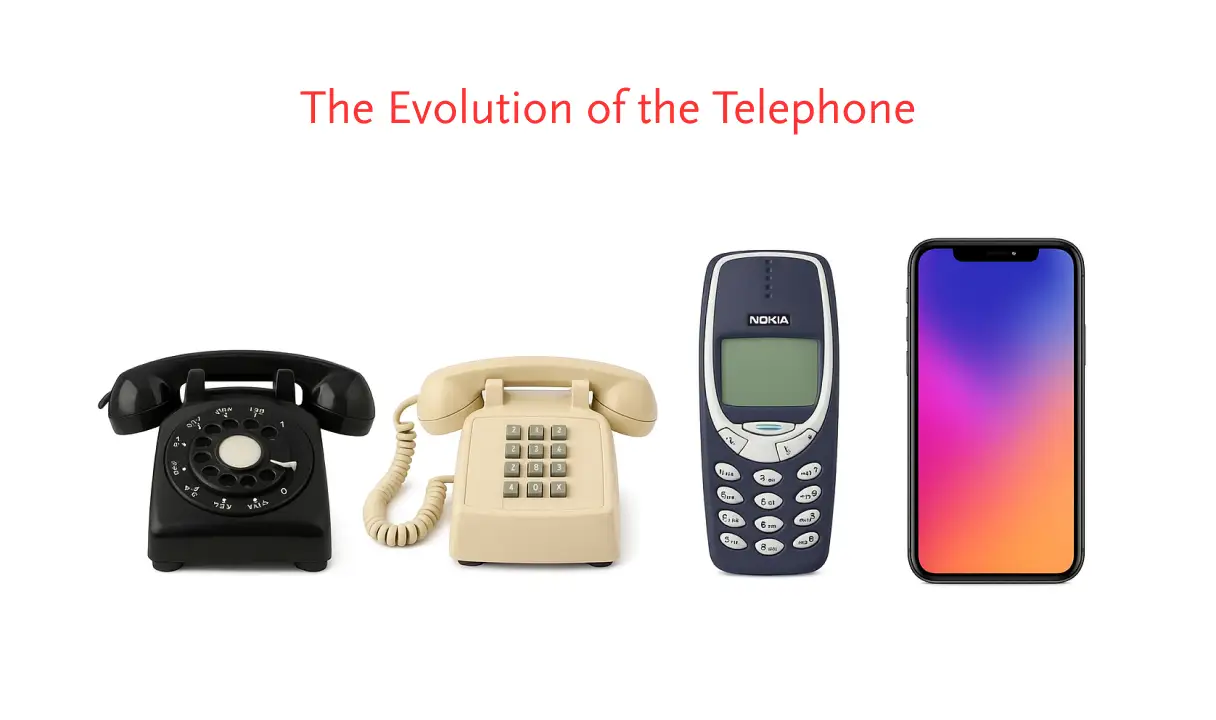

So observation is a research technique that focuses on catching people in the act — how they actually perform tasks. And products are tools that make these tasks easier, automate them, or sometimes remove them altogether. For example:

- As a kid, I used a rotary phone at a PCO. (Hard)

- Later, I got a push-button phone. (Easy)

- Then came the Nokia, which let me call on the move. (Easier)

- Finally, the iPhone put a computer in my pocket. (Easiest)

Now, we do thousands of tasks using just our smartphone.

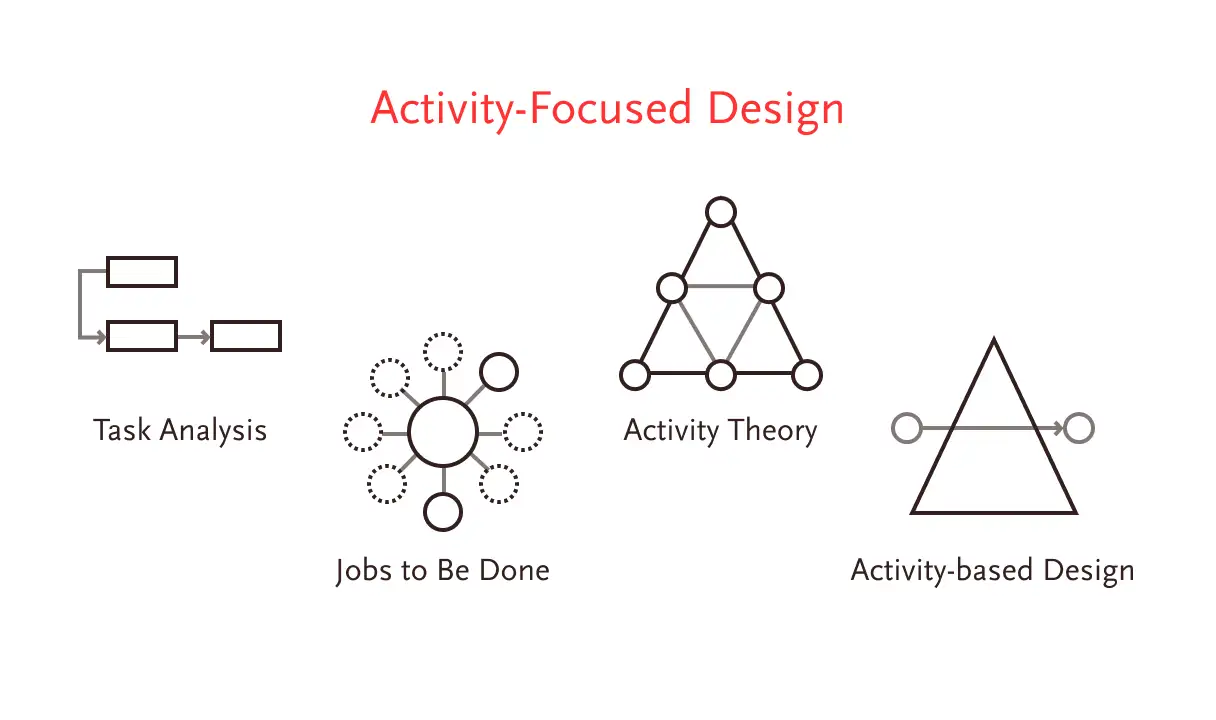

So a task or an activity is the ultimate unit upon which you want to put your focus on. And there are a few processes out there that help you to analyze tasks and streamline them such as:

- Task analysis

- Jobs to be done (JTBD)

- Activity theory

- Activity based design

In today’s article we’ll talk about Task analysis.

Task Analysis: An Example

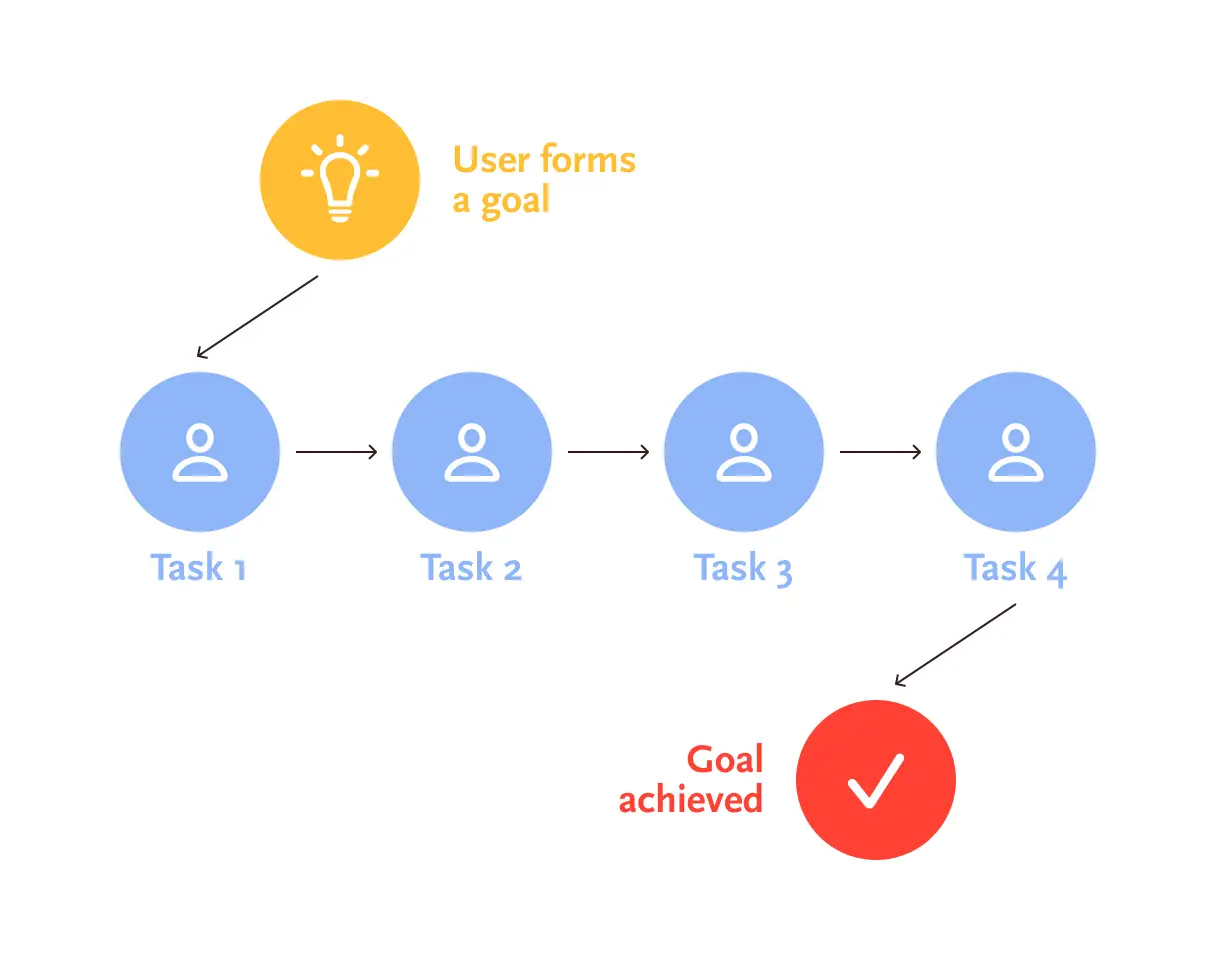

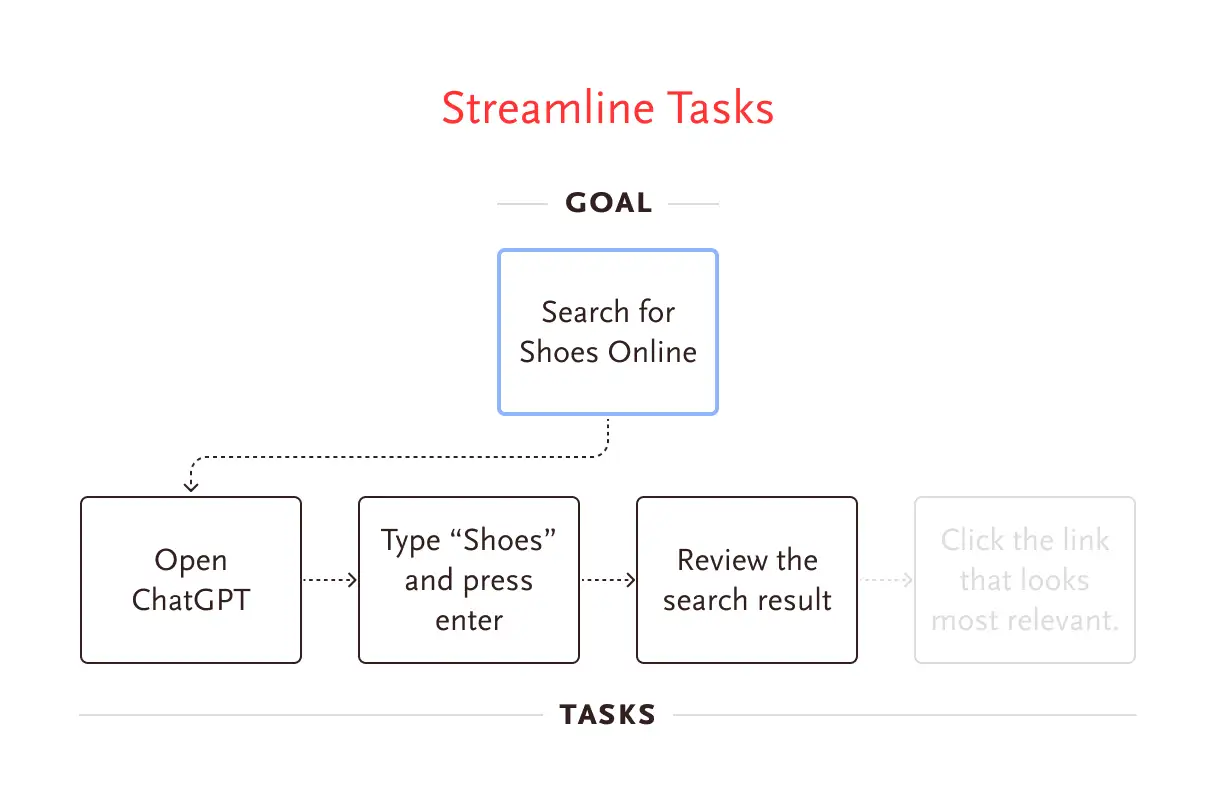

It’s a process that focuses on the tasks people perform to reach a goal. For example: how do you search online?

- Open a browser

- Type a query and press enter

- Review the search results

- Click, click, click…

That’s just 4 tasks to reach your goal. But is this really the most streamlined way to search online? Couldn’t you remove or automate a step to make the process simpler and easier to use? Is this the best we can do?

Not, really. This used to be the best we had. But today we’ve got ChatGPT, Grok, Perplexity, Gemini, Meta—you name it. Now you just:

- Open ChatGPT (or Grok, Perplexity…)

- Ask your question

- Get the answer

They’ve eliminated the back-and-forth of clicking through links just to find what you need. Now you get exactly what you ask for with results that are better-formatted. They even predict your next steps (tasks), saving you a lot of time. Let’s look at the process.

Task Analysis: The Process

As I mentioned earlier, task analysis focuses on the tasks people perform to reach their goals. There are no fixed steps in task analysis, but most UX teams typically follow four to six steps:

- Goal — Define the goal you want to achieve. For example, buying a t‑shirt from an e‑commerce website.

- User — Identify and profile the users who perform the task. This is where your user personas come in handy.

- Task — Outline the tasks people must complete to reach their goal. For example, to buy a t‑shirt, users need to search for it, add it to the cart, provide their address, and make payment.

- Document — Document the goals and tasks using a task analysis diagram, a hierarchical task diagram, sequence diagram, or a flowchart.

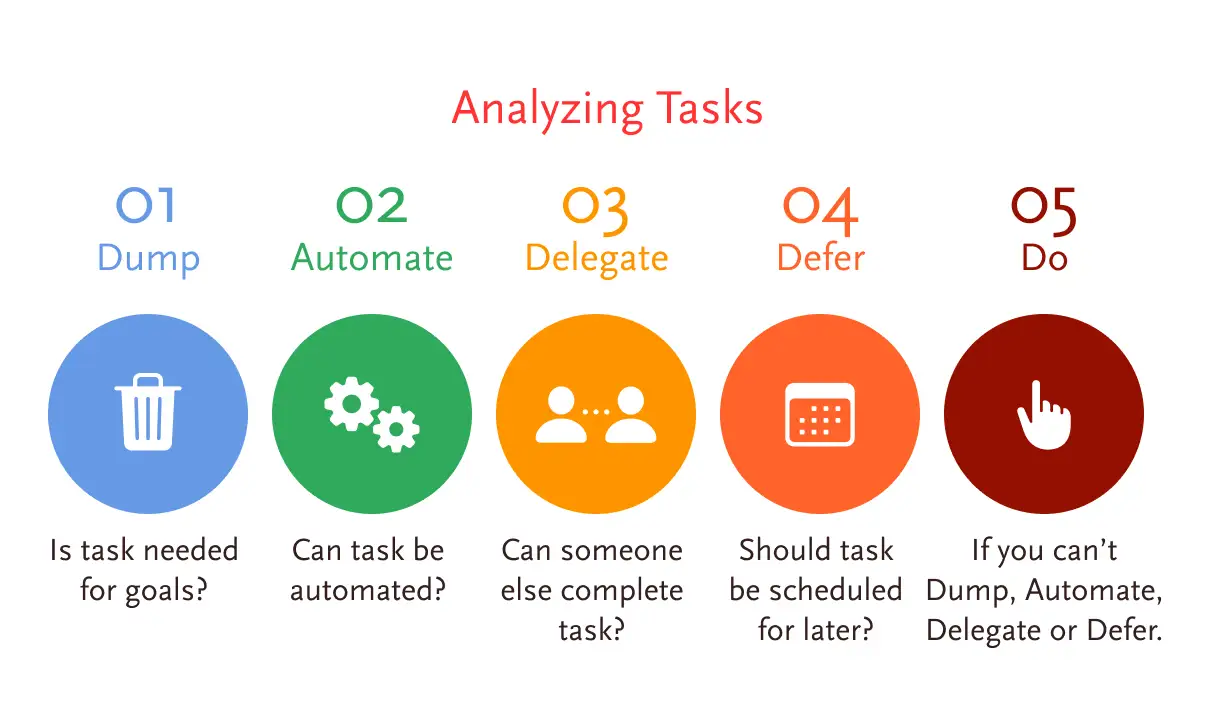

- Analyze — Ask questions such as: “Do we need all those tasks?”, “Is any redundant task?”, “Can the system handle a task?”. And based on your findings, streamline the process by improving, automating, or removing tasks.

There are several ways to identify these tasks. You might ask research participants to think aloud while performing them, or conduct a contextual inquiry observing people working on tasks in their natural environment. If you can’t find anyone, you can even perform the activities yourself.

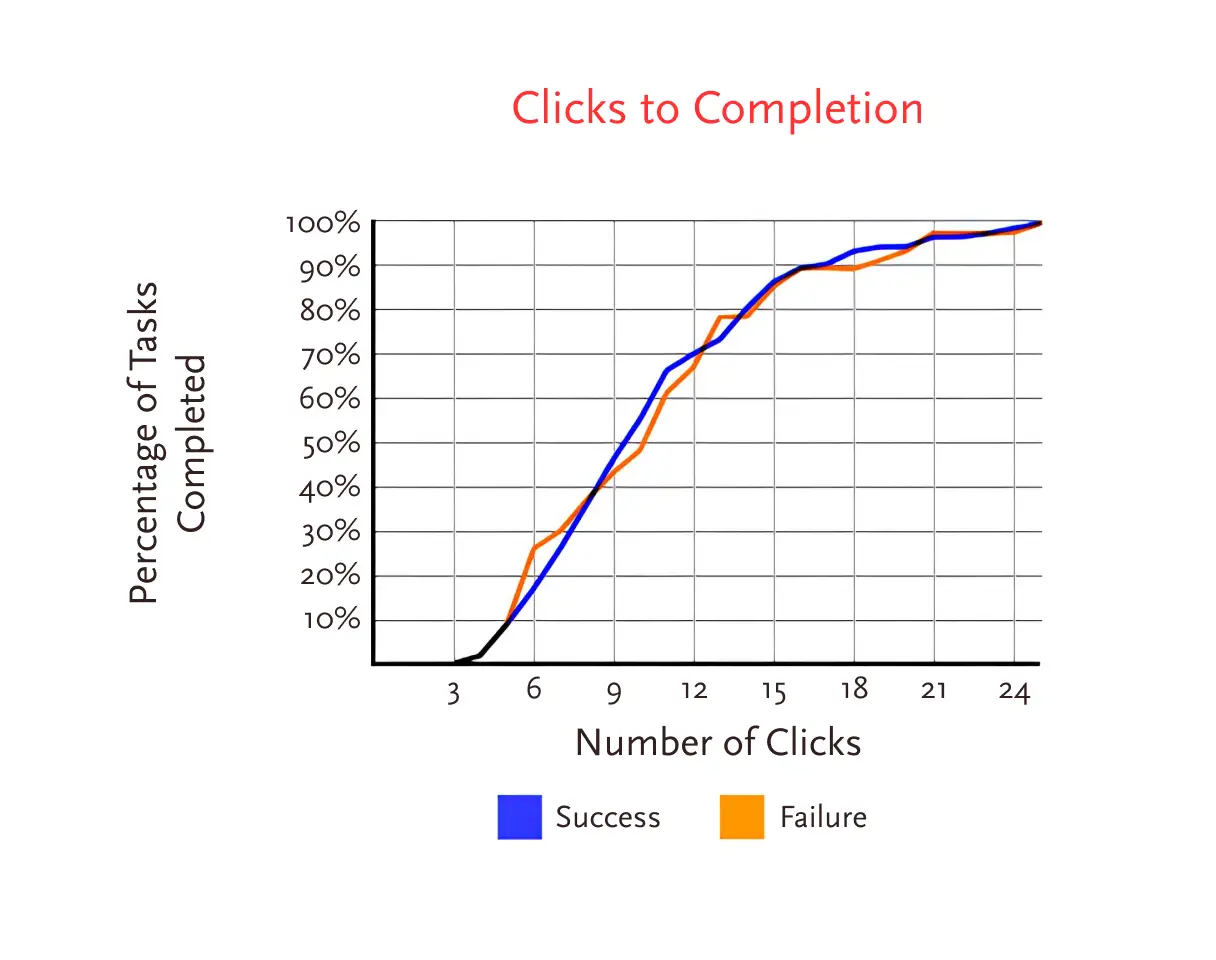

Also, keep in mind that task analysis isn’t only about removing tasks. Sometimes, it’s about adding one. For example, your users might need an extra explanation to better understand a task. Contrary to popular belief, people don’t really care about the number of clicks—as long as they know they’re on the right track. So, over optimization doesn’t always make sense.

In short remember two things:

- Don’t make tasks too specific or too general. For example, “View search results” is too specific, while “Fill out the address form” is too general.

- When starting a new project, stay tool-agnostic to write tasks in an interface-independent way. This not only mirrors real-life scenarios but also gives you the flexibility to explore multiple solutions.

Task Analysis: Strengths and Weaknesses

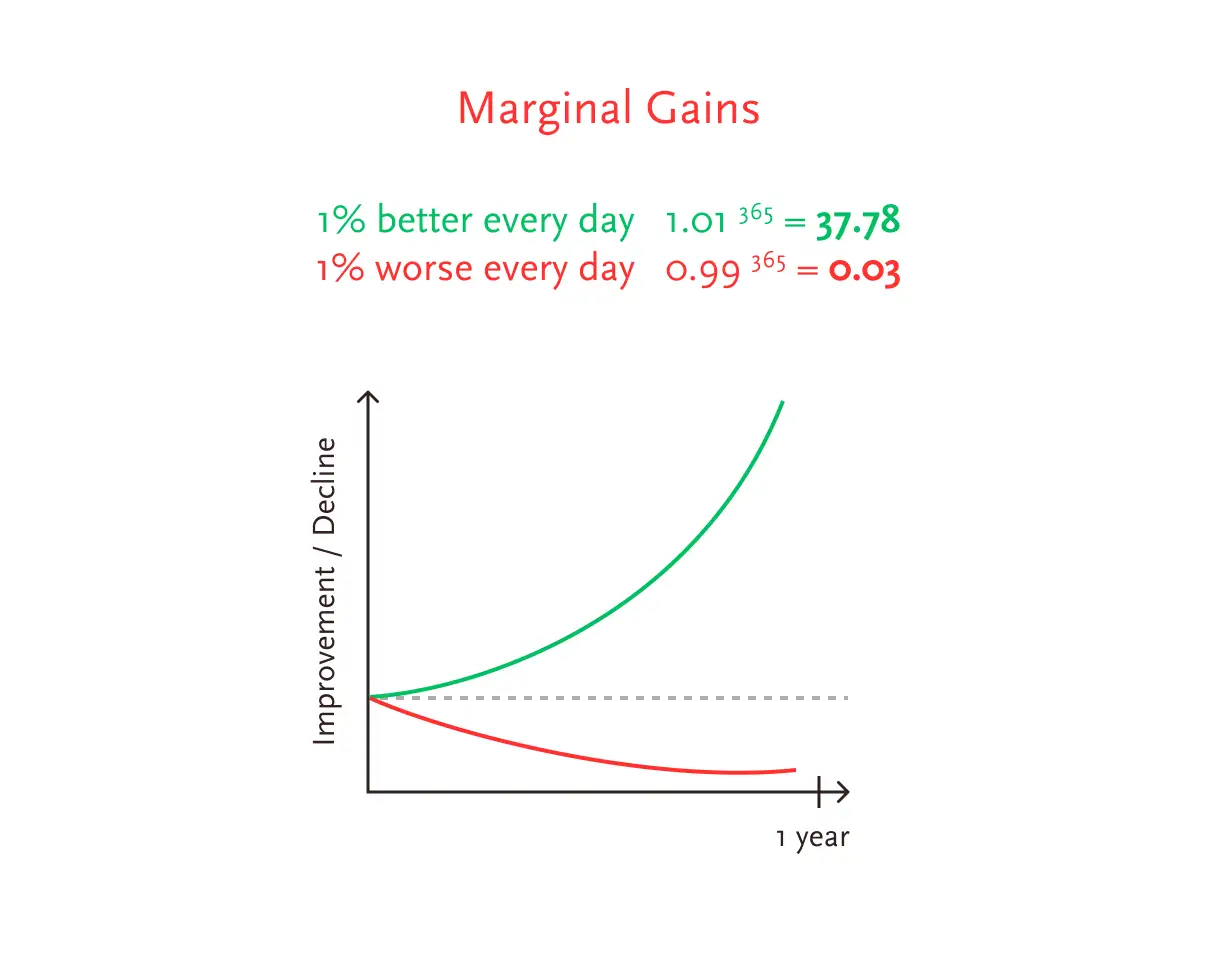

Task analysis works best when the focus is on streamlining individual goals. By breaking a goal into smaller tasks and subtasks and then improving each part, the combined result can be remarkable.

James Clear highlights this in his book Atomic Habits. In the very first chapter he describes how Dave Brailsford, performance director of the British Cycling team, used his concept of “marginal gains” to transform a mediocre team into champions.

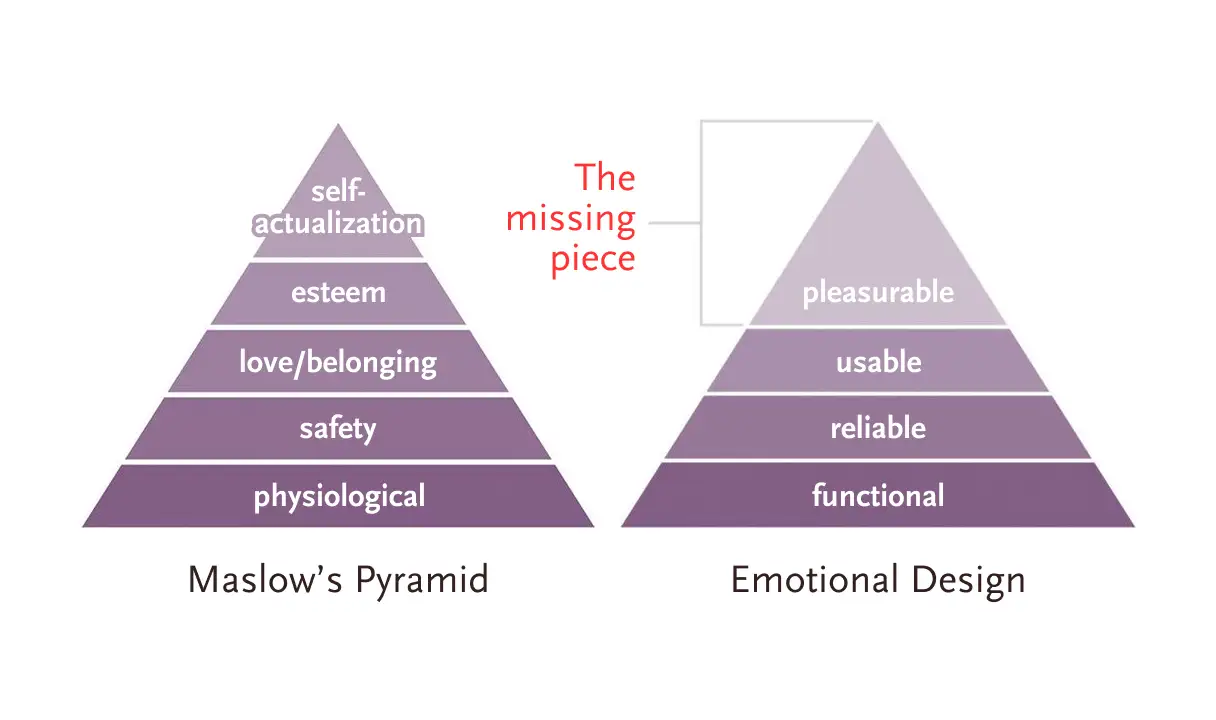

One weakness of task analysis is that it focuses solely only on tasks without considering the emotional state of users which can often play a crucial role in making or breaking an experience.

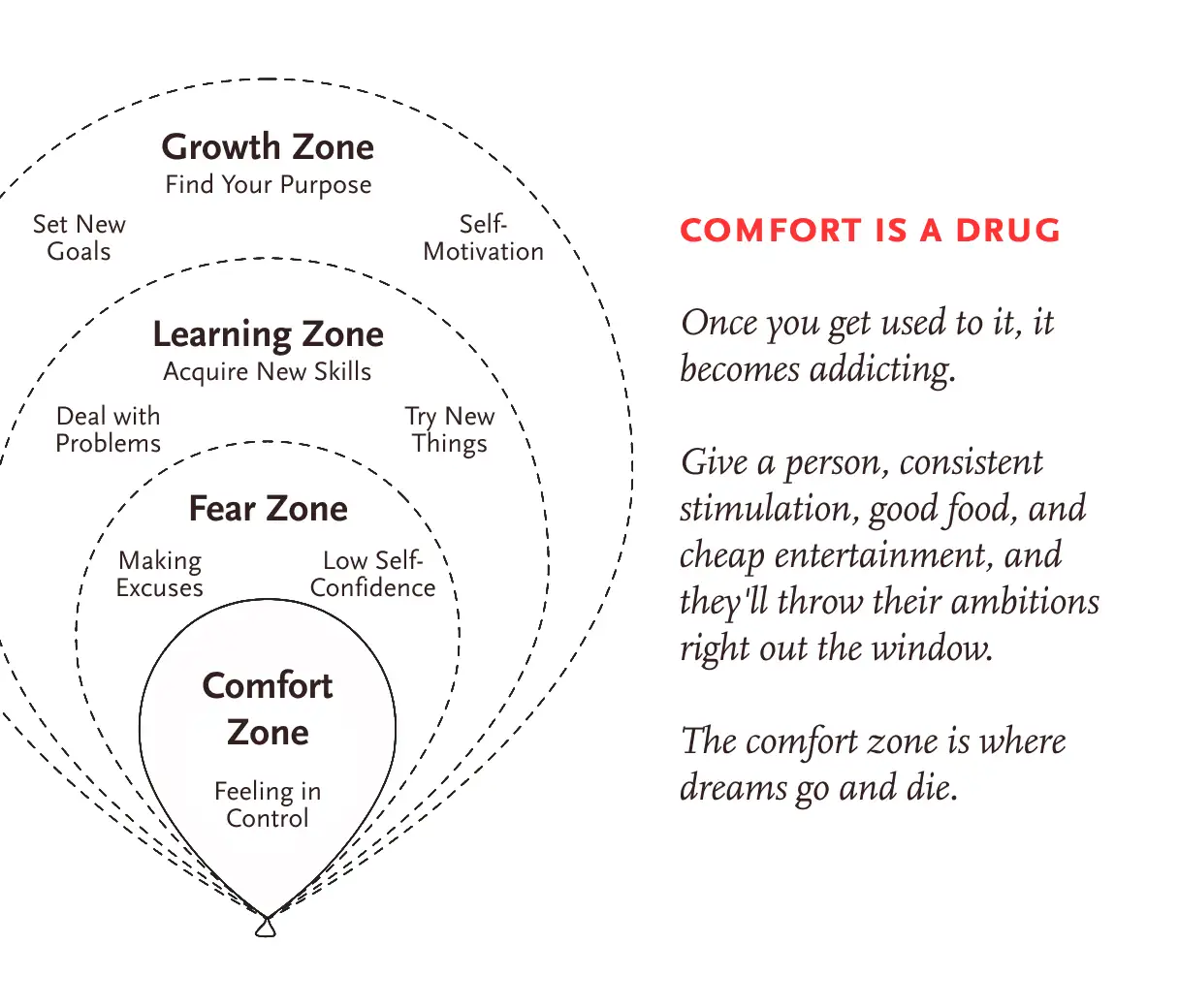

Often we simply follow what the industry is already doing. For example, much of the e‑commerce industry models itself after Amazon, copying whatever Amazon does. We’re afraid to change the status quo. After all, why reinvent the wheel if it seems to be working fine?

But this mindset comes with a cost. By staying “in the league,” we avoid stepping out into the real world to observe how people actually behave. But that’s exactly where the most valuable insights lie.

When you set technology aside and stop thinking about implementation, you begin to see people as they really are. By simply observing, you uncover their true needs and desires.